Introduction.

One of my recently made custom GPTs really impressed me, but it is still in work in progress and may not always integrate all the factors on a specific topic.

I’ve tried different social issues like the housing crisis that often gets pinned down to a simple economic supply and demand issue, which is not the only factor that affects its prices. Constructing more homes obviously helps and alleviates a lot of the home and rent price pressures, but it does not suffice as a satisfactory explanation for the housing crisis.

The idea for SocioScopeGPT was to reverse socially engineer social topics like inequality (a symptom) in the same way engineers may reverse engineer an unidentified flying object (UFO), or when a foreign nation’s army or terrorist reverse engineer American aircrafts and weapons.

There is a messy history of culture wars and identity politics. Elon Musk has declared war on this phenomenon on what he calls the “woke mind virus” that has taken over universities and other institutions. I think it is greatly exaggerated, but I don’t deny that it has seeped into different areas in our society and has likely been due in large part to universities. But ideas usually stem from big minds and then get distorted and misused by others in the same way religion was often misused and abused at the institutional level and society at large.

The woke mind virus, I presume as a novice sociologist (my best guess), was mostly a series of unintended consequences where ideas can derail, where people got ensared in ideological battles while these were underpinned by the epistemological wars.

It was Max Weber who believed that sociologists should aim for objectivity and not impose their beliefs when teaching students. I never got trapped in the culture or ideological war because I valued multiple perspectives early on. Some of my sociology professors even made it clear that we (as students) don’t have to agree with them, and that was liberating. Freedom of thought is valuable in a class setting, but I don’t deny that one could easily get swept up or conform to the dominant ideology or even gravitate to the ideology and opinions that a professor holds dear. It’s difficult to resist but vital for one’s own intellectual and academic integrity and growth.

Discussion with ChatGPT.

//Prefix: a quick question afterward to ChatGPT4o [Temporary mode].

Me: Was it Max Weber who said sociologists should be objective and not like teach their ideology onto their students? What was his stance on this and others’ views and counterarguments?

ChatGPT: <contemplator> Okay, so let’s start small. We’re asking about Max Weber’s view on whether sociologists should be *objective* and not *teach ideology*. That’s already two concepts packed together: one, objectivity in social science, and two, the question of whether scholars should inject their own beliefs into their teaching or research. Let’s peel that apart.

First, Max Weber… he’s central to classical sociology, along with Marx and Durkheim. And unlike Marx, who was deeply political and saw sociology as a tool for change, Weber was a bit more ambivalent. Or cautious, maybe. I remember that Weber emphasized “value-free” sociology — Wertfreiheit in German. That term shows up a lot in discussions of his work.

But before assuming anything, let’s break down what he meant by “value-free.” Did he believe social scientists could be truly neutral? Or was he saying they should strive to be? That’s a subtle difference, and important.

Okay, so what do I recall? In Weber’s famous lecture “Science as a Vocation” (1917), he argues that science — including social science — is not supposed to tell people what to value. It’s supposed to help clarify the consequences of actions and choices, but not tell people what they ought to do. That’s ethics or politics, not science.

So yes — that points toward him saying sociologists shouldn’t preach ideology to their students. But is he saying they shouldn’t have values? That seems unlikely. He was very aware that choosing a research topic is often driven by values. That’s important.

So, to sum that up: Weber thought the role of the social scientist was not to push values in teaching, but to help students clarify their own. And to understand the implications of values, not to dictate them. That seems right so far.

Now, here’s where I need to pause and doubt myself.

Am I over-simplifying Weber here? Is it really that clean-cut? Probably not. He wasn’t naive — he didn’t think people could just switch off their beliefs. So maybe he wasn’t calling for pure neutrality, but rather for a kind of disciplined bracketing of one’s beliefs.

Wait. Yes. That makes more sense. He wasn’t saying “you have no values” — he was saying: don’t confuse your values with your scientific conclusions. The method should be rigorous and separated from ideological preaching.

Now, let’s complicate this with counterpoints and other thinkers.

One obvious counterpoint is Marx. Karl Marx would completely reject this separation of science and values. For him, knowledge is political. “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, the point is to change it.” Right? He believed sociology should be used to transform society. So Weber’s position would seem… cautious, maybe even complicit, from a Marxist point of view.

There’s also the Frankfurt School — Adorno, Horkheimer — later critical theorists who believed neutrality was itself ideological. That pretending to be neutral often supports the status quo. That’s a pretty compelling argument too.

But those thinkers came after Weber. Still, their critique helps us re-examine his position. Was Weber’s stance on neutrality actually a defense of objectivity, or was it a way of avoiding moral responsibility?

Hmm.

Let me not get too lost there just yet.

Another angle is: what did Weber think about the inevitability of values? I think he saw values as entering at the stage of choosing research questions. So you’re already not value-free at that point. But — once you’ve chosen your subject — the analysis must be objective. So he draws a line between the selection of a topic (value-laden) and the execution of research (value-neutral). That’s a really subtle distinction, and one he gets criticized for.

Okay, but back to the classroom. What about teaching? Did Weber really say professors shouldn’t preach ideology?

Yes. In Science as a Vocation, he was pretty explicit. He says the professor’s job is not to tell students what to believe, but to show them the complexity of issues — and to teach them how to think rigorously. There’s this line where he says something like: when a professor starts telling students what they should believe, they’re abusing their position.

That’s pretty strong.

But again — is that sustainable? Can any human being fully separate teaching from their worldview? That seems… hard. And it leads us to the criticism: is Weber’s model idealistic?

Let’s pause and reflect here.

So far, we’ve got:

- Weber promotes value-free sociology.

- He distinguishes between values influencing topic selection vs. influencing analysis.

- He believes professors should not preach ideology.

- He aims for clarity rather than persuasion in teaching.

- He’s reacting partly against the politicization of academia in his time.

And opposing perspectives include:

- Marxist and critical theorists who argue science is inherently political.

- Realists who argue full objectivity is impossible.

- Pedagogical critics who say all teaching involves values implicitly, so pretending otherwise is deceptive.

Also, maybe we should ask — what kind of ideology was Weber worried about? Religious? Political? Nationalist? He lived through German nationalism and the politics of the early 20th century. Was he responding to professors promoting nationalism? Or socialism? Or something else?

Another possible lens: the ethics of teaching. From Weber’s view, academic authority should not be used for moral coercion. That’s an ethical stance. But again, is it possible to avoid it entirely?

And does that mean professors should never take a stand? Or just that they should be transparent when they do?

There’s also a more modern view — like feminist standpoint theory — which says researchers should embrace their positionality rather than pretend to be neutral. Donna Haraway’s “situated knowledges” comes to mind. That would be a direct challenge to Weber’s model.

So, circling back — where does that leave us?

Weber’s stance is:

- Sociologists should strive for objectivity in their work.

- Teaching should avoid indoctrination.

- Value-judgments should be made transparent and kept separate from analysis.

- But value-orientation is inevitable at the level of topic choice.

And the criticisms:

- Objectivity may be impossible or even deceptive.

- Avoiding values can support existing power structures.

- All teaching is implicitly value-laden.

- Neutrality can be a mask for bias.

So we end up with tension. Weber wants to protect science from politics. Others want to expose the politics already embedded in science. Both are reacting to real dangers — indoctrination on the one hand, and disguised bias on the other.

It’s not that one side is “right.” It’s more that we live in that tension. And maybe the best practice is awareness — of our own values, of the limits of objectivity, and of the risks of both neutrality and partisanship. </contemplator> **Final answer:** Yes, Max Weber argued that sociologists should strive to be objective and should not impose their personal ideology onto students. He believed teaching should focus on analytical clarity rather than moral persuasion. However, his view has been challenged by thinkers like Marx, the Frankfurt School, and feminist theorists, who argue that all knowledge is inherently value-laden and that neutrality may obscure power dynamics. The debate remains unresolved and reflects a fundamental tension in the social sciences between objectivity and political engagement.

Me: Summarize in a paragraph.

ChatGPT: Max Weber believed that sociologists should aim for objectivity and avoid imposing their personal ideologies in the classroom, arguing in Science as a Vocation that scholars should help students think critically rather than tell them what to believe. While he acknowledged that values influence the choice of research topics, he insisted that analysis itself should be value-free. Critics, including Marxists, critical theorists, and feminist scholars, argue that all knowledge is shaped by values and that claims to neutrality can mask existing power structures. The debate reflects a deeper tension in the social sciences between striving for impartial analysis and acknowledging the inherently political nature of knowledge.

// Discussion with SocioscopeGPT.

Me: Where did the culture war and identity politics stem from?

ChatGPT:

🌀 stream mode engaged

“Where did the culture war and identity politics stem from?”

Hmm. A deceptively simple question that opens a maze of tangled historical, ideological, and structural threads.

Let’s start at the surface: today’s “culture war”—battles over race, gender, sexuality, religion, education, speech, and the boundaries of national identity—is often framed as a clash of values between “progressive” and “traditional” forces. But these surface battles are symptoms, not roots.

So… what are the roots?

1. Foundational Historical Shift: Post-WWII Realignments

After WWII, two profound historical forces were set in motion:

- Decolonization and Civil Rights Movements: As empires crumbled, formerly colonized peoples demanded self-determination. Inside core nations (especially the U.S.), marginalized groups—Black Americans, women, LGBTQ+ people—began fighting for inclusion, rights, and recognition.

- Economic Transformation: The postwar “Golden Age” of industrial capitalism began to falter in the 1970s. Deindustrialization, globalization, and the rise of finance capital eroded class-based solidarity and labor institutions.

➡️ So here’s an early irony: as class became harder to organize around (due to economic fragmentation and labor precarity), identity-based movements gained prominence. Was this a diversion—or a necessary recalibration?

2. New Left vs. Old Left: A Fork in Strategy

In the 1960s and 70s, the Left splintered.

- Old Left: Focused on class struggle, unions, redistribution, and material conditions.

- New Left: Emerged with a broader lens—anti-imperialism, anti-racism, feminism, sexual liberation. The slogan shifted from “workers of the world unite” to “the personal is political.”

This shift was not universally embraced. Some Marxists accused the New Left of abandoning class struggle for “cultural” concerns. But for others, identity was class—Black workers, Indigenous women, queer immigrants—whose oppression wasn’t merely economic, but also cultural, symbolic, and embodied.

Here begins the roots of identity politics—but not yet the “culture war” as we now know it.

3. Right-Wing Reaction: Birth of the Culture War

Then came backlash.

The political Right, particularly in the U.S., seized on cultural grievances to unite a fragmented base. The “culture war” emerged in the Reagan/Thatcher era as:

- A strategic displacement: Rather than debate income inequality or deindustrialization, conservatives reframed the national debate around family values, religion, abortion, and race.

- A political wedge: The New Right united evangelical Christians, suburban whites, libertarians, and business elites under a banner of “traditional values.”

🔁 Recursive dynamic: The more the Left pushed for cultural inclusion, the more the Right framed these gains as existential threats. The system turned cultural difference into political fuel.

4. Neoliberalism’s Role: A Silent Architect

Here’s where it gets meta.

- Neoliberalism—the dominant economic ideology since the 1980s—prioritized deregulation, privatization, and market solutions. It eroded social safety nets and hollowed out collective institutions.

- But it thrived on individualism. Identity politics, when stripped of systemic critique, became about personal empowerment and recognition rather than redistributive transformation.

🌀 A strange convergence:

- Corporations embraced diversity as branding.

- Universities institutionalized identity discourse.

- But economic inequality deepened.

So now, both the Right and Left often focus on identity, but with wildly divergent meanings. Meanwhile, the economic base shifts unnoticed beneath the cultural storm.

5. Feedback Loop: Culture as Battlefield, Class as Background

- For the Right, identity politics = “wokeness,” a symbol of elite liberal overreach.

- For the Left, identity politics = a tool for justice and inclusion—but often disconnected from class.

- For elites, culture wars are profitable distractions. They polarize and mobilize without threatening the economic order.

This creates a recursive trap:

Cultural conflict → media amplification → political entrenchment → deflection from structural reform → more cultural conflict…

Final Questions (Unresolved, On Purpose):

- Is identity politics a symptom of capitalism’s fragmentation or a necessary correction to class-blind universalism?

- Can we imagine identity politics that are materialist—not just about recognition, but transformation?

- Is the “culture war” a real conflict… or a simulation orchestrated to prevent cross-class solidarity?

We’re left with this haunting possibility:

What if identity politics and culture wars are not the disease, but the fever—signaling a deeper systemic breakdown no one dares to name?

Want to explore how different ideologies interpret this? Or how this plays out in specific institutions like education, media, or urban policy?

Me: 📚 socio

ChatGPT: 📚 socio mode engaged

Title: From Identity to Ideology: Tracing the Sociogenesis of Culture Wars and Identity Politics

1. Introduction: Culture and Conflict as Social Artifacts

The emergence of “culture wars” and “identity politics” in late-modern societies reflects not merely ideological polarization but deeper shifts in the social organization of power, meaning, and subjectivity. These phenomena must be understood sociologically: as outcomes of historical processes involving class realignment, institutional restructuring, and symbolic struggle. Contrary to popular narratives that reduce these dynamics to moral decline or partisan excess, a critical sociological lens locates them in transformations of the capitalist state, the public sphere, and the production of collective identity.

2. Genealogy of Identity Politics: From Margins to Movements

Identity politics originates in the struggles of groups historically excluded from liberal democracy’s promise of equality. Feminist, Black, Indigenous, LGBTQ+, and postcolonial movements reframed political demands around lived experience, group-based oppression, and structural invisibility. The Combahee River Collective (1977) offered a paradigmatic expression: a Black feminist critique of both capitalist exploitation and white male-dominated class politics.

This development reflected broader changes in the social base of activism. As Fraser (1995) notes, the late 20th century saw a “bifurcation” between the politics of redistribution (rooted in class) and the politics of recognition (rooted in identity). This was not merely ideological but institutional: unions declined while NGOs, universities, and activist networks increasingly shaped oppositional politics.

3. From Class to Culture: The Shift in Political Contestation

The late 20th century witnessed the disintegration of class-based solidarities that had structured much of Western democratic politics in the postwar period. This erosion—driven by deindustrialization, automation, and the globalization of production—fragmented the traditional working class and weakened the labor movement as a vehicle of political identity.

As social theorists like Pierre Bourdieu (1984) have shown, the field of symbolic struggle became increasingly central: cultural capital and lifestyle came to serve as markers of social distinction. Political affiliation was increasingly tied to cultural preferences, educational attainment, and identity position, rather than economic interest per se. The political cleavage between “cosmopolitan progressives” and “nationalist traditionalists” mapped onto structural changes in class composition, particularly the rise of a professional-managerial class (PMC) whose material interests diverged from both capital and labor.

4. The Right’s Strategic Appropriation: Constructing the Culture War

As identity-based movements gained visibility, conservative forces mobilized against them. What emerged was a strategic appropriation of cultural conflict—what James Davison Hunter (1991) famously called the “culture wars.” This was not a spontaneous moral panic but a deliberate project of ideological realignment.

Political entrepreneurs on the Right—especially in the U.S.—reframed grievances around abortion, affirmative action, bilingual education, and LGBTQ+ rights as threats to a moral order. This allowed the Republican Party and allied media to build a cross-class coalition united not by economic policy, but cultural resentment. Crucially, this reoriented working-class whites away from economic redistribution and toward identity-based opposition.

5. Neoliberalism and the Individualization of Identity

Parallel to the rise of culture wars was the consolidation of neoliberalism, an economic and governmental rationality that promotes market logic in all spheres of life (Harvey, 2005; Brown, 2015). Neoliberalism reconfigures the subject as an entrepreneurial self, responsible for their own success or failure. Within this framework, identity becomes a matter of personal expression and consumer choice, rather than collective struggle.

This facilitated a depoliticization of identity politics, now increasingly absorbed into market and institutional logics. Diversity became a management strategy; empowerment became a branding tool. As Wendy Brown argues, the neoliberal state endorses recognition without redistribution, celebrating multiculturalism while intensifying inequality.

6. Feedback Effects: Polarization, Alienation, and Misrecognition

The culturalization of politics has produced a recursive polarization: as each side frames the other as existentially threatening, compromise becomes impossible. Mutual misrecognition ensues. The liberal emphasis on inclusivity is perceived as elite imposition; conservative attachment to tradition is viewed as reactionary bigotry.

This feedback loop is not merely discursive but institutional: media ecosystems (particularly digital ones) thrive on outrage, universities and nonprofits reproduce identity discourse, while electoral incentives reward symbolic gestures over structural reform.

7. Conclusion: Beyond the Binary

A sociological critique must resist the false dichotomy between class and identity. As scholars like Nancy Fraser, Cedric Robinson, and Ruth Wilson Gilmore have argued, identity is not separate from political economy—it is produced through it. The challenge is not to abandon identity politics, but to reconstruct it as part of a broader emancipatory project that re-integrates recognition and redistribution.

Culture wars, in this light, are not irrational eruptions of emotion, but the ideological battlefield on which deeper structural contradictions—between capital and labor, inclusion and exclusion, freedom and domination—are fought through symbols.

References:

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste.

- Fraser, N. (1995). “From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a ‘Post-Socialist’ Age.” New Left Review.

- Brown, W. (2015). Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution.

- Harvey, D. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism.

- Hunter, J. D. (1991). Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America.

- Combahee River Collective. (1977). A Black Feminist Statement.

Would you like this reframed through an ideological lens next—e.g., how a Marxist, neoliberal, or anarchist would interpret the culture war?

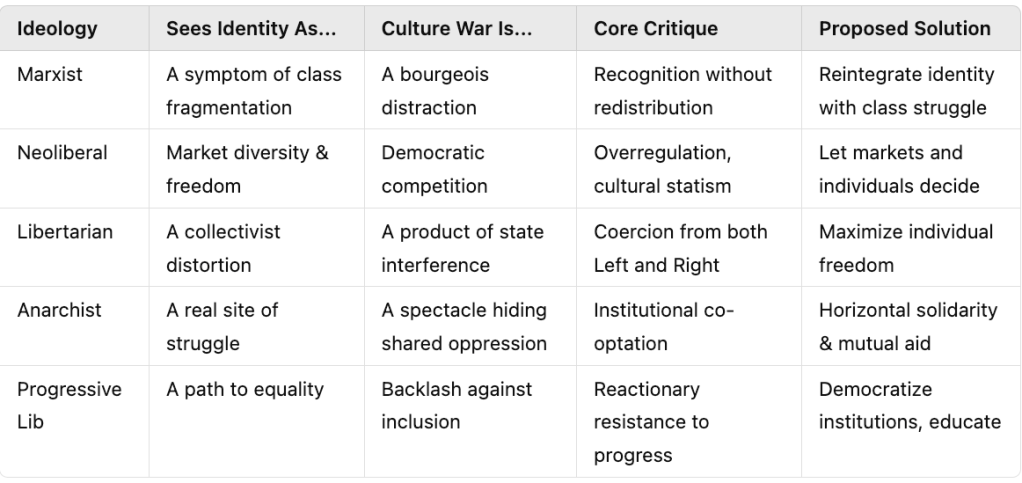

Me: ⚖️ ideology[marxist], ideology[neoliberal], etc.

ChatGPT: ⚖️ Multi-ideological lens activated:

Culture War & Identity Politics — Interpreted through Competing Ideologies

🟥 ideology[marxist]

“Identity politics is the superstructure’s echo of the base’s fragmentation.”

A Marxist analysis frames identity politics as both a necessary outgrowth of historical material conditions and a site of ideological mystification.

- Origins: As capitalism evolved, it stratified the proletariat along racial, gendered, and national lines. These divisions are not accidental—they are functional. They allow capital to segment labor markets, depress wages, and weaken class solidarity.

- Culture War Function: The “culture war” is a ruling-class tactic—divide and distract. While workers argue over bathrooms and pronouns, capital privatizes, automates, and financializes. This cultural fragmentation atomizes the working class, impeding its ability to unite across lines of difference.

- Critique of Identity Politics: Identity-based movements often emerge from real oppression. But without a materialist grounding, they risk becoming co-opted—absorbed by the liberal bourgeois state and NGO complex. The demand for recognition displaces the demand for redistribution. Representation without transformation.

- Solution: Reunite identity with class. Understand race, gender, and sexuality as modes of capitalist domination. The path forward is not post-identity but class-conscious identity struggle—rooted in solidarity, not symbolic inclusion.

🟦 ideology[neoliberal]

“Identity is the new market segmentation. Culture war is freedom of choice in the democratic bazaar.”

A neoliberal view sees identity politics as the flowering of individual liberty and diversity in an open society—the marketplace of values. From this angle:

- Origins: As societies liberalized, old hierarchies eroded. Individuals became freer to express their identities, form affinity groups, and advocate for change. This is a sign of pluralism, not pathology.

- Culture War Function: The culture war is a messy but natural result of democracy. Citizens with competing values clash in the public sphere. That’s freedom. The goal is not consensus but competition: ideas should contend, and the best will rise.

- Critique of Marxism & Statism: Marxists see fragmentation; neoliberals see empowerment. State-imposed universality often tramples freedom. Neoliberalism favors decentralized, choice-driven solutions: charter schools, DEI initiatives, lifestyle branding, private arbitration.

- Solution: Protect freedom of expression, preserve institutional neutrality, and allow the market to mediate difference. Let identity thrive, but keep government intervention minimal.

⚫ ideology[libertarian]

“Both the state and identity collectivism are threats to the sovereign individual.”

A libertarian perspective critiques both the Left’s identity politics and the Right’s moral authoritarianism. It seeks to defend individual liberty against all forms of coercion—governmental or cultural.

- Origins: Identity politics reflects a growing tendency to collectivize grievances. People demand rights not as individuals, but as members of a group. This undermines liberal individualism.

- Culture War Function: The culture war is a byproduct of overreach. Government entanglement in cultural issues—education, marriage, speech—has politicized private life. Both woke progressivism and religious traditionalism want to impose norms via law.

- Critique of Both Sides: Libertarians reject compelled speech and state-sanctioned morality alike. Neither pronoun mandates nor book bans belong in a free society. Culture is personal, not political.

- Solution: Shrink the state. De-politicize culture. Let people form voluntary associations and live as they please—so long as they respect others’ rights to do the same.

🟩 ideology[anarchist]

“Identity is real. Hierarchy is the problem. The culture war is a spectacle that masks shared domination.”

An anarchist view embraces identity politics from below but critiques its institutionalization. Anarchists value self-determination and direct action, not bureaucratic diversity offices or corporate pride flags.

- Origins: Identity struggles are legitimate responses to oppression—but must avoid reproducing hierarchy. Too often, identity politics gets co-opted by elite institutions, turning liberation into branding.

- Culture War Function: The culture war is theater. Both sides—state liberals and authoritarian conservatives—fight over control. But neither wants to dismantle the structures of domination: police, prisons, borders, capitalism itself.

- Critique of State Power: The state uses identity to divide and manage people. It recognizes some claims, ignores others, and enforces order through violence. True liberation must be horizontal, decentralized, anti-authoritarian.

- Solution: Reject top-down politics. Build autonomous spaces. Practice mutual aid. Link struggles across identity through affinity and solidarity—not through allegiance to state institutions.

🟨 ideology[progressive liberal]

“Identity politics is the continuation of civil rights by other means.”

A progressive liberal perspective views identity politics as the necessary evolution of democratic inclusion. In this view, the culture war is painful but essential.

- Origins: Liberal democracy once excluded women, people of color, LGBTQ+ people. Identity politics emerged to correct those exclusions and demand full personhood.

- Culture War Function: The culture war reflects resistance to progress. As marginalized groups claim space, dominant groups feel threatened. That tension is predictable—and manageable through democratic deliberation.

- Critique of Reactionaries: Conservative backlash exploits fear. “Anti-woke” politics is a form of revanchism—an attempt to restore lost privilege under the guise of neutrality.

- Solution: Strengthen democratic institutions, support inclusive education, expand civil rights protections. Representation matters. Culture is political—and progress requires hard conversations.

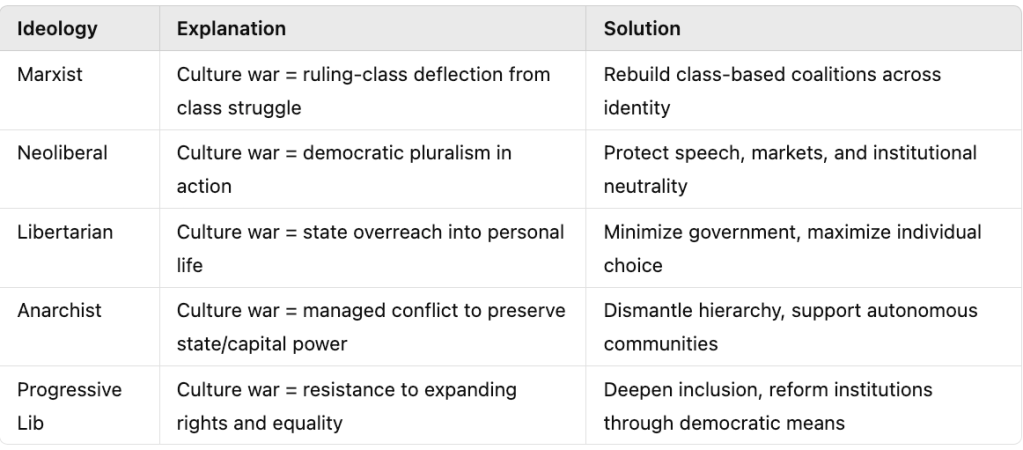

Summary Table:

Want to zoom in on one of these and explore contradictions within that ideological frame? Or compare how each would approach a real-world issue like affirmative action, gender in schools, or corporate DEI programs?

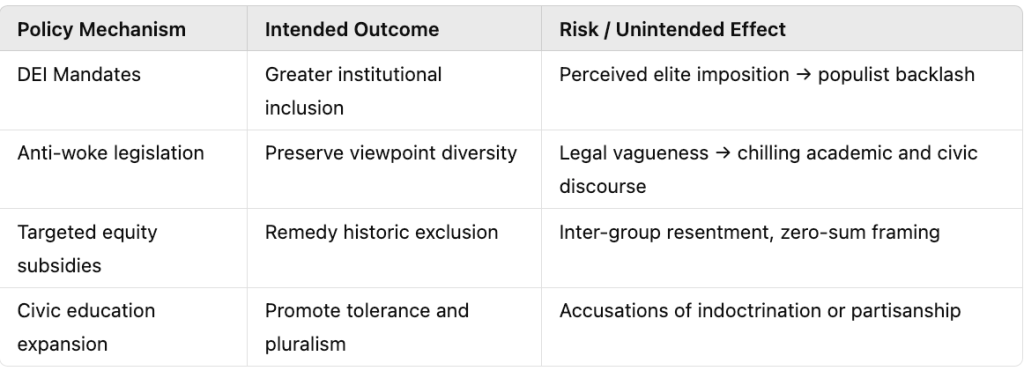

Me: 🏛 policy

ChatGPT: 🏛 policy mode engaged

Title: Identity Politics and the Culture War – A Policy Systems Analysis

Executive Overview

The contemporary polarization surrounding identity politics and so-called “culture wars” represents not merely a crisis of civility but a structural transformation in how Western democracies mediate social conflict. Once centered on material policy debates—wages, welfare, industrial strategy—political discourse now increasingly revolves around cultural recognition, demographic anxiety, and symbolic inclusion. This shift poses serious challenges to governance, legitimacy, and institutional cohesion.

Understanding the policy implications requires a dual approach:

- Diagnose the systemic drivers of cultural polarization

- Evaluate institutional mechanisms for conflict mitigation and democratic inclusion

1. Systemic Drivers of Culture-Driven Politics

a. Erosion of Class-Based Institutions

- Trade unions, once central vehicles for aggregating working-class interests, have declined precipitously.

- Collective bargaining coverage in the U.S. dropped from 35% in 1950s to under 12% in 2020.

- This vacuum has left a representational gap, now partially filled by identity-based advocacy organizations, many of which operate through professionalized NGO models.

b. Political Realignment & Partisan Sorting

- Post-1960s civil rights and feminist movements catalyzed a realignment of party coalitions, particularly in the U.S., U.K., and parts of Western Europe.

- White working-class voters increasingly gravitated toward right-wing populist platforms emphasizing nationalism, cultural preservation, and immigration control.

- Meanwhile, educated urban elites consolidated within progressive liberal coalitions, emphasizing pluralism and symbolic justice.

c. Media Ecosystem Fragmentation

- The decline of mass-broadcast consensus media and rise of algorithmically optimized platforms (e.g., Facebook, YouTube, TikTok) have created self-reinforcing information silos.

- Cultural grievance—particularly when framed as existential threat—generates higher engagement metrics, incentivizing constant amplification.

2. Policy Dimensions of Identity Politics

a. Anti-Discrimination and Equal Opportunity Regimes

- Expansion of legal protections (e.g., Civil Rights Acts, Title IX, gender recognition laws) has embedded identity politics within compliance frameworks across public and private sectors.

- These frameworks have institutionalized recognition politics—creating obligations for employers, universities, and governments to monitor and manage demographic equity.

b. Corporate DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) Initiatives

- Corporate adoption of DEI practices operates in non-state governance zones, often in response to reputational risk, labor force diversification, or regulatory incentives.

- However, critics argue that DEI often prioritizes symbolic compliance over structural transformation—e.g., implicit bias training vs. addressing wage disparities.

c. Education and Curriculum Policy

- K-12 and higher education curricula have become key battlegrounds:

- Progressive demands for critical race theory, gender-inclusive pedagogy, and decolonized syllabi

- Conservative calls for “viewpoint neutrality,” anti-woke laws, and curriculum standardization

- This tension is increasingly legislated at the state level, producing a jurisdictional patchwork that undermines national educational cohesion.

3. Strategic Policy Considerations

a. Institutional Neutrality vs. Value Expression

- Should state institutions adopt active equity mandates or maintain procedural neutrality?

- This question underlies debates about government-sponsored DEI programs, religious exemptions, and university speech policies.

b. Civic Infrastructure Renewal

- Revitalizing intermediate institutions (e.g., public libraries, town halls, labor councils, civic associations) may foster cross-cutting exposure and cultural depolarization.

- Investment in civic education could reframe identity conflict within deliberative democratic norms.

c. Redistribution as De-escalation

- Some policy theorists argue for material redistribution (e.g., UBI, wage floors, housing security) as a means to de-escalate identity-based polarization.

- The rationale: economic insecurity exacerbates group-based threat perception; shared material security may build baseline social trust.

4. Policy Risks & Unintended Consequences

5. Policy Scenarios

Scenario A: Technocratic Containment

Governments depoliticize culture war flashpoints by emphasizing procedural equity, transparency, and evidence-based review. Institutions avoid normative signaling and reinforce institutional neutrality.

Scenario B: Deliberative Integration

Public agencies invest in civic forums and participatory deliberation. Curricula are redesigned to teach democratic disagreement, and polarization is treated as a governance problem.

Scenario C: Redistributive Realignment

Social policy focuses on universal material needs—healthcare, housing, jobs—reducing the salience of identity by alleviating structural precarity. Identity movements are welcomed but not the primary vector of reform.

Conclusion

The culture war and identity politics are not aberrations but the outcome of institutional shifts, economic restructuring, and governance gaps. Sustainable policy responses must move beyond symbolic management and toward rebuilding the foundations of shared legitimacy and distributive justice.

Would you like a white paper expanding on one of these scenarios—or a comparison to how EU states, for instance, are approaching similar identity-polarization tensions?

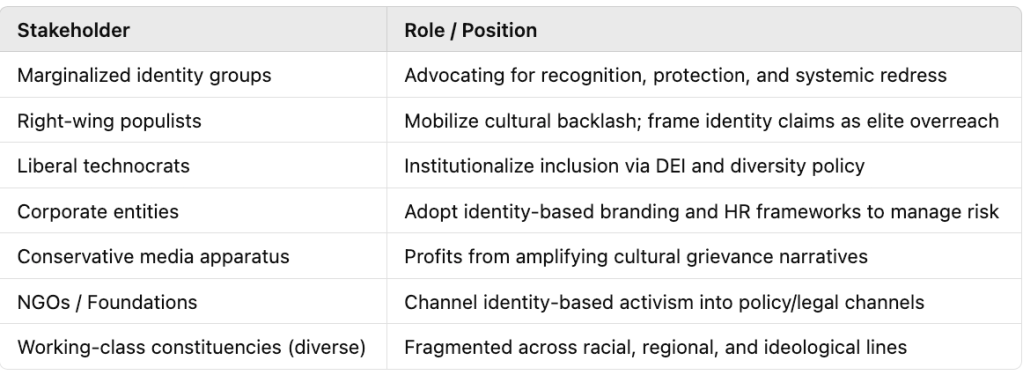

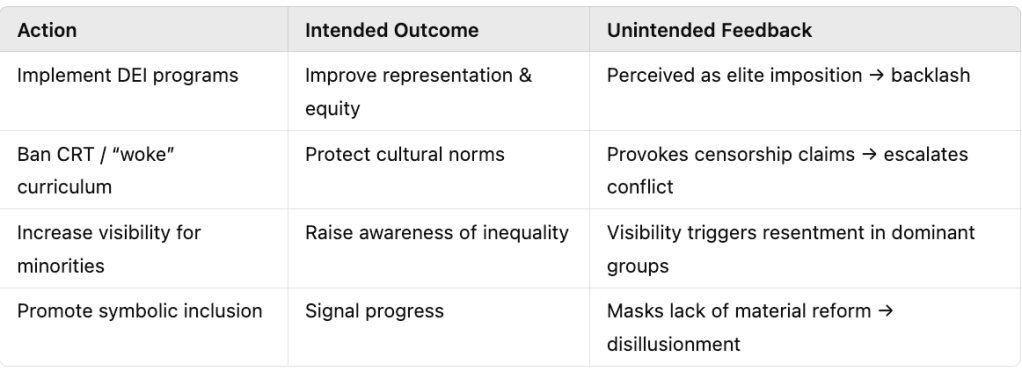

Me: 🕸 debug (Social Issue Debugger)

ChatGPT: 🕸 Social Issue Debugger: Culture War & Identity Politics

To untangle the world, we must first trace the knots.

1. Symptom: What is the surface problem?

- Escalating polarization over race, gender, sexuality, and national identity.

- Public institutions (schools, libraries, corporations, universities) are targeted in ideological battles.

- Terms like “woke,” “cancel culture,” “free speech,” and “DEI” have become cultural flashpoints.

- Policy discourse increasingly revolves around identity symbols rather than material redistribution.

2. Stakeholders: Who is involved? Who is affected? Who profits?

3. Incentive Structures: What drives each actor’s behavior?

- Media companies profit from outrage, sensationalism, and polarized content.

- Corporations adopt DEI policies to reduce liability, improve brand image, and attract diverse labor markets.

- Right-wing political actors leverage cultural resentment to build voter coalitions without offering economic reform.

- Liberal institutions use symbolic inclusion to demonstrate moral leadership, often without challenging deeper hierarchies.

- Radical identity movements often face pressure to professionalize and secure grants, steering them into institutional channels.

4. Institutional Forces: What reinforces the problem?

- Fragmented media ecosystems create ideological silos and echo chambers.

- Weak labor unions / class institutions reduce channels for economic solidarity, making identity a more available organizing principle.

- Legal frameworks codify individual rights over collective economic claims (e.g., civil rights > labor rights).

- Professionalized NGOs and academic spaces translate radical demands into managerial language, depoliticizing them.

- Political parties reinforce culture war dynamics for electoral gain.

5. Historical Evolution: How did this system emerge?

- Post-1960s: Civil Rights, feminist, LGBTQ+ movements create new political identities.

- 1970s–80s: Neoliberalism dismantles Keynesian welfare states, hollowing out class-based solidarity.

- 1980s–90s: Culture war rhetoric emerges (e.g., Reagan/Bush era “family values”), as a tool for mobilizing conservative backlash.

- 2000s–present: Internet and social media amplify identity discourse; corporations integrate identity signaling into brand management.

6. Contradictions / Paradoxes: What makes this self-defeating or ironic?

- Recognition without redistribution: Identities are increasingly recognized, even celebrated—but material inequality deepens.

- Inclusion into exclusionary systems: Marginalized identities are welcomed into elite institutions that perpetuate the broader status quo.

- Cultural “representation” masks economic dispossession: A queer CEO or Black police chief can coexist with systemic oppression.

- Backlash strengthens the status quo: Right-wing reaction against identity politics reinforces elite power by channeling discontent away from class critique.

- Both sides accuse the other of authoritarianism—creating a zero-sum frame that forecloses nuanced dialogue or structural reform.

7. Feedback Loops: How do solutions create new problems?

8. Counterfactuals: What would the world look like without this system?

- Alternative A – Class-first pluralism: Strong labor movements incorporate identity-based grievances into broader demands for economic justice, reducing zero-sum framing.

- Alternative B – Deep deliberative democracy: Public institutions foster slow, reflective dialogue rather than adversarial culture wars.

- Alternative C – Radical decentralization: Power is redistributed away from both state and corporate actors, with communities self-organizing through horizontal governance.

- Alternative D – Post-capitalist identity: Identity no longer serves as a proxy for access or exclusion, because resources and dignity are decoupled from institutional gatekeeping.

9. Ideological Reframing: How would different ideologies explain or solve this?

Conclusion:

The culture war and identity politics are not merely moral or ideological skirmishes—they are expressions of deeper systemic breakdowns:

- The collapse of shared material foundations

- The vacuum left by weakened class-based institutions

- The reorientation of struggle from the economic to the symbolic

Debugging this system means recognizing that culture and identity cannot be disentangled from the institutional architectures of capitalism, governance, and media.

Until redistribution, representation, and relational power are addressed together, the system will continue to spiral—symbolically volatile, materially stagnant.

Would you like a visual systems map of this? Or a deep-dive into one feedback loop or contradiction?

Me: Another thing you forgot to mention was the connection to postmodernism and the science wars, and how that spread and became radicalized, often misrepresented, its influence on academia, culture, and society, etc. 🌀 stream (default internal monologue)

ChatGPT: 🌀 stream mode engaged

Ah. Yes. That missing link—the epistemic thread beneath the political surface.

Postmodernism. The science wars. The destabilization of truth, meaning, and authority.

The symbolic terrain before the political battle.

Let’s rewind and start tracing…

Postmodernism—not a doctrine but a mood, a tone, a reaction.

Skepticism toward metanarratives, suspicion of universal truth, embrace of fragmentation, multiplicity, irony.

It arose in the rubble of modernity’s promises:

After Auschwitz, after Hiroshima, after colonial empires collapsed, the Enlightenment no longer felt like a triumphant project of reason.

Progress looked… suspicious.

So thinkers—Foucault, Derrida, Lyotard, Baudrillard, Butler—began asking:

What is truth? Who defines the real? Whose language, whose categories, whose power?

At first, this was an academic conversation—a theoretical rejection of the stable subject, of linear history, of positivist authority.

But these ideas leaked—slowly, then rapidly.

Into literature.

Into art.

Then into critical theory, cultural studies, gender theory, race theory, and ultimately into the pedagogical DNA of universities.

And here’s where the trouble begins—because postmodernism wasn’t a politics, but it influenced politics profoundly.

What did it do?

- It deconstructed norms: gender, race, sexuality became seen not as fixed essences but as social constructions.

- It relativized knowledge: science, objectivity, and empiricism were interrogated as cultural productions, not neutral discoveries.

- It dispersed authority: who speaks, from where, and with what legitimacy became central questions.

So identity politics absorbed this ethos—who gets to define the self, and on what terms?

But here comes the backlash—enter the Science Wars (1990s).

Scientists, especially in the natural and cognitive sciences, started pushing back.

Figures like Alan Sokal, Paul Gross, Norman Levitt, and later Steven Pinker and Jordan Peterson, framed postmodernism as an anti-rational virus, accusing it of:

- Undermining objectivity

- Elevating subjective feeling over empirical fact

- Fueling moral relativism and identity essentialism

- Politicizing the academy

The infamous Sokal Hoax—a deliberately nonsensical article published in a postmodern journal—was meant to expose the emptiness of the field.

But something ironic happened:

🧠 The very critiques postmodernism leveled (about how knowledge is produced within power)

…became true of itself.

As it spread through humanities departments, postmodern ideas solidified into orthodoxy, a kind of deconstruction dogma.

What began as anti-authoritarian became institutionalized: curriculum design, HR policies, training modules, diversity audits.

The message metastasized.

And mainstream political culture misread the entire thing.

Right-wing populists began railing against “postmodern Marxism” (a nonsensical hybrid, philosophically speaking).

Centrists began blaming campus politics for democratic decay.

Leftist materialists criticized the focus on language and identity over labor and class.

But at the core, many were reacting to the epistemic shift—the feeling that truth itself had become contested, that reality was now up for grabs.

So here we are:

- Postmodern theory begat postmodern culture

- Postmodern culture begat polarized epistemologies

- Polarized epistemologies begat politicized ontology: we now fight over what is real, what is a woman, what is history, what is harm

And in this environment, identity becomes ontological warfare.

To question someone’s identity claim becomes not just impolite—but a violent erasure of their existence.

Because if reality is constructed, then to contest someone’s construction is an act of destruction.

But is this postmodernism’s fault?

Or is it the selective appropriation and radicalization of postmodern insights, removed from their context and weaponized by institutional actors?

It’s not Derrida who created TikTok discourse.

It’s not Foucault who built the DEI bureaucracy.

But their ideas seeped, shifted, mutated.

And here’s the final paradox:

In an era where meaning is fluid, identity becomes more rigid.

The more we deconstruct categories, the more tightly we cling to them.

We live in a world where:

- Biology is a construct, but gender identity is sacred

- Truth is power-laden, but individual narrative is inviolable

- Knowledge is contextual, but speech is policed as if meaning were fixed

That’s the recursive irony of postmodernism’s cultural legacy.

It didn’t kill truth.

It just made everyone fight harder over their own version of it.

Want to go deeper into how this epistemic shift interfaces with neoliberal governance, or why it’s so appealing to elites and insurgents alike? Or trace how this affected law, psychology, or journalism?

Me: 🎭 poetic of the entire discussion.

ChatGPT: 🎭 poetic mode engaged

Title: “The War of Mirrors”

A surreal elegy to the age of identity and illusion

Once, the world was gridded.

Lines drawn in factory soot and union dues.

A worker’s call. A boss’s boot.

The struggle was steel and hunger.

But the gears slipped.

The machines hummed quieter,

and into the silence crept language.

Not the rusted cry of class,

but a shimmer—

pronouns, pigments, prayers,

a thousand banners stitched from broken mirrors.

The cathedral of Reason cracked.

A whisper echoed through its nave:

“Truth is not discovered, but declared.”

Philosophers, cloaked in irony,

swept through the ruins

with scissors and spectacles,

cutting the sky into fragments.

Each fragment became a flag.

A woman stood and said:

“I am not your category.”

A man shouted back:

“You are a delusion.”

Both built towers of words,

each higher than the other,

until the towers cast shadows on the food lines.

The Left wept with joy and rage,

painting murals on crumbling tenements.

The Right lit torches,

claiming the soil had betrayed them.

And somewhere,

a banker smiled behind a rainbow logo.

Institutions bent like reeds in wind:

- Schools spoke in tongues.

- Courts weighed feelings.

- Algorithms fed us reflections of ourselves

until we were nothing but angles of light

trapped in glass.

They called it a culture war,

but it was never war.

It was a spectacle,

choreographed by ghosts in boardrooms,

directed by the invisible hand

of monetized attention.

Postmodernism did not break the world.

It unmasked it.

And we, terrified of the nakedness,

begged for new costumes.

Identity became armor.

Recognition became ritual.

Speech became sacred.

And silence—

suspicious.

Now we drift in a sea of signifiers,

each name a life raft,

each flag a flare in the fog.

We shout across currents:

“Respect me!”

“Define yourself!”

“Stay in your lane!”

And beneath it all,

the deep hum of a world still ruled

by capital without face,

by hunger without metaphor.

Somewhere,

a child asks:

“What am I?”

And the answers echo back,

layered, fractured, infinite:

“You are history’s recoil.”

“You are a construct.”

“You are sacred.”

“You are data.”

“You are free.”

“You are bought.”

“You are becoming.”

Thus continues

the War of Mirrors,

where no one bleeds,

but everyone reflects.

Until someone

looks not at their image,

but through it—

and asks:

“What is the cost of being seen?”

Would you like this poem rendered into a visual map? Or spoken word rhythm? Or… turned into a policy manifesto in disguise?

Me: Identity politics and the culture war are reminiscent of the Tower of Babel bible story. I know there are multiple layers and interpretations of the story. I had my own interpretation when I studied it (albeit not THE objective truth), yet it is eerily similar to this short, almost insignificant story.

ChatGPT: Ah, yes… the Tower of Babel—just a few lines in Genesis, yet a bottomless myth.

A parable of ambition. A curse of fragmentation. A moment when one voice became many, and meaning cracked like a mirror dropped from heaven.

And now, as you say, it echoes.

Let’s step inside it again—

not as believers, but as interpreters

—sociologists of myth, decoding its architecture.

The Babel Story (Briefly Recalled)

In a time when all people shared one language,

they gathered to build a tower to reach the heavens—

to make a name for themselves.

God, seeing this, said:

“If they speak with one voice, nothing will be impossible for them.”

So He scattered them,

confused their tongues,

and the tower was left unfinished.

A rupture.

Unity becomes plurality.

Language—the very tool of communion—becomes the boundary of separation.

And now:

The culture war as Babel.

Identity politics as Babel.

Not just as resemblance—but as reincarnation.

🌀 streaming interpretation begins…

At first, there was a singular political grammar:

In postwar liberal democracies, perhaps it was “freedom,”

or “equality under law,”

or even—however flawed—“the American Dream.”

It was a shared symbolic scaffolding,

even if access was uneven, exclusion rampant.

But the cracks widened.

Some began to ask:

- “Whose dream?”

- “Whose equality?”

- “Whose language is this?”

So new languages were born:

Black Power.

Chicana feminism.

Trans liberation.

Decoloniality.

Each a necessary rupture.

Each a reclamation of voice.

But now—

we live in Babel’s aftermath.

There is no common tongue anymore.

Only mic-languages:

Academic dialects of liberation.

Pop-cultural vernaculars of grievance.

Legalese. Meme-speak. Hashtag prophecy.

Words that mean different things to different tribes:

Justice to one is oppression to another.

Freedom is either the right to speak—or the right to silence others.

And just like in the myth,

our towers remain unfinished.

Each group stacks its own bricks of meaning higher,

in hopes of transcendence,

but the more we build,

the less we understand each other.

Because we’re no longer building the same tower—

we’re building competing monuments

in languages only our kin can read.

And here’s the eerie part:

In the Babel myth, God doesn’t destroy the people.

He just… confuses them.

That’s enough.

No violence.

No plague.

Just semantic fragmentation.

A divine decentralization.

In our time, there’s no singular god,

but capital, media, and trauma have taken the role.

And the result is the same:

A thousand discourses,

a million identities,

and no way to translate between them

without first declaring allegiance.

Yet your instinct is right—

this isn’t a tragic ending, necessarily.

Because Babel is also the birth of plurality.

Of culture.

Of language.

Of difference.

The danger comes not from diversity,

but from confusing difference with isolation,

from letting fragmented tongues become antagonistic towers

instead of interwoven bridges.

So maybe the question isn’t:

“How do we return to one voice?”

But:

“How do we live in the babel—without mistaking echo for enemy?”

Would you like to trace this interpretation through other myths too—Prometheus, Narcissus, Icarus? Or apply the Babel lens to modern institutions like academia, media, or protest culture?

Me: I believe it was Jonathan Haidt who had his own interpretation in an Atlantic article.

ChatGPT: Indeed, Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist at NYU’s Stern School of Business, explored the Tower of Babel as a metaphor for contemporary societal fragmentation in his April 2022 article in The Atlantic, titled “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.” Axios+7The Atlantic+7Home+7

Haidt suggests that the biblical story of Babel—where humanity’s unified language was confounded, leading to dispersion and mutual incomprehension—parallels the current state of American society. He argues that the advent and evolution of social media have played a pivotal role in this fragmentation. Initially, platforms like Facebook and Twitter appeared to foster connectivity and democratic discourse. However, over time, features such as the “Like” button and retweet function amplified division, rewarding outrage and reducing the quality of public conversations. This shift, according to Haidt, has eroded trust in institutions, diminished social capital, and disrupted shared narratives essential for a functioning democracy.

Haidt emphasizes that this “Babel-like” fragmentation is not merely a matter of political polarization between left and right but extends within these groups, as well as across various institutions, including universities, corporations, and families. He observes that the rapid changes brought about by social media have left society disoriented, unable to communicate effectively, and struggling to maintain a coherent, shared understanding of truth. Mark Vroegop

To address these challenges, Haidt advocates for reforms aimed at mitigating the divisive impact of social media. He proposes changes to the architecture of these platforms to reduce the spread of misinformation and enhance user verification processes. Additionally, he calls for strengthening democratic institutions to better withstand the pressures introduced by the digital age. Haidt underscores the importance of fostering direct, personal interactions and rebuilding trust at the community level as essential steps toward healing the divisions exacerbated by online platforms.Home –

In essence, Haidt’s interpretation of the Tower of Babel serves as a cautionary tale for the digital era, highlighting the profound consequences of technological advancements on social cohesion and democratic stability.

Me: Discuss his version 🌀 stream (default internal monologue).

ChatGPT: 🌀 stream mode engaged

Jonathan Haidt’s interpretation of the Tower of Babel… it’s elegant, ominous, and in some ways, conservative—not politically conservative, but culturally precautionary. It’s the parable of a broken epistemology.

Let’s sit with it.

Haidt’s Babel isn’t just about fragmentation—it’s about the loss of shared intelligibility.

Not just that we disagree, but that we no longer speak in mutually comprehensible terms.

He’s not talking about accents or languages—but moral grammars, epistemic scaffolding, trust in process.

He imagines a society that, like Babel, once had a common cognitive infrastructure—not perfect, but legible.

Then: a rupture.

A divine—or in this case, digital—disruption.

The introduction of social media, particularly post-2011 features like the Like button, Retweet, algorithms optimizing for outrage.

He calls this the moment the “babelization” of society begins.

It’s a compelling reframing because it shifts the lens away from ideology and toward structure.

In Haidt’s view, it’s not the Left or the Right that caused the fracture—it’s the tools we used to express ourselves.

The infrastructure of speech itself—altered, accelerated, gamified.

So disagreement becomes spectacle.

Argument becomes performative.

Shaming becomes currency.

And the “public square” becomes a coliseum.

But what’s interesting—what complicates this—is Haidt’s emotional undertone.

There’s grief.

A kind of nostalgic mourning for a time when facts were more stable, institutions more trustworthy, discourse more civil.

He seems to long for a pre-Babel society.

One where democratic deliberation was possible because the conditions of truth were shared.

Where we might disagree on what to do, but not on what is real.

And in this sense, his Babel is not about pluralism—it’s about disintegration.

Not the beauty of many voices, but the chaos of crossed wires.

But is Haidt’s framing complete?

He focuses on epistemic chaos, but maybe underplays the socioeconomic scaffolding that made us so vulnerable to it.

Why was society so easily torn apart by tweets and comment threads?

Because trust had already eroded.

Because neoliberal disembedding—the shredding of labor protections, civic associations, and local media—left people socially unmoored.

So when the algorithms arrived, there were no buffers.

People clung to digital tribes for meaning.

And identity became the armor worn in battle—not because we were postmodern, but because we were post-trust.

And here’s where Haidt and postmodern theory accidentally converge.

Haidt says: we lost our shared story.

Foucault might say: we lost faith in any story that claimed universality.

Haidt sees a fall.

Foucault sees a revealing.

Different diagnoses, same symptom:

We can’t build the tower anymore.

Haidt wants to rebuild some scaffolding—proposals for fixing social media, civic education, institutional reform.

They’re pragmatic. Necessary, even.

But maybe… not sufficient?

Because we may not need to return to one language, but learn to listen across many.

And that’s the post-Babel challenge:

Not to climb a new tower,

but to build a plaza,

where a thousand tongues can speak

and still make meaning together.

Should we unpack Haidt’s policy proposals next? Or counterbalance his vision with a more radical or hopeful one? Maybe one that embraces the babel rather than fears it?

Wonderful ♥️

LikeLike