Sir Arthur Eddington was a scientist whom I became aware of some weeks ago when I was researching the history of scientific peer review due to Eric Weinstein’s disdain for that process. I came across one of his books, published in 1938, that had one of the words that was used before the term “peer review” came into existence. Eddington was a giant in the 20th century, especially after validating Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity with his expedition of the solar eclipse. Einstein was relatively unknown in the intelligentsia, besides his small circles of friends and peers.

People often forget that Einstein’s papers were radical during his time and were largely ignored and, by some measure, even dismissed. Only a few prominent scientists took an interest, and that’s when they became recognized as significant and potentially groundbreaking. That’s what makes Einstein’s story glorious. You could probably count the number of people in one hand who actually understood Einstein’s theory of relativity, and Eddington was among them. Like many other scientists, I was surprised by their mystical outlook on life. Many times we learn history, or get fed a post on social media of famous figures, yet hardly ever learn about their philosophical views. The more I look into many past giants, the more I learn of their perennial philosophy, many of whom had great depth of knowledge and wisdom when it came to spirituality and their own religion.

–

I have been abusing the Deep Research Mode on ChatGPT to gain more insights, historical knowledge, and even test out theories or claims. There are two main claims made by Ken Wilber (known for Integral Theory) in his book, Quantum Questions, that I wanted to test out with AI, which I believe hold much water.

Note: You can read the full chat log here.

1) Descriptive claim: Many founders of modern physics personally held mystical or religious worldviews.

2) Boundary claim: They themselves insisted physics does not provide proof of those worldviews, and kept the two domains separate.

I can understand the caution to separate mysticism and science — same as religion and science. Despite the caution made by folks like Ken Wilber, I still argue that these two can and sometimes blend or at least inform each other. There is an inclination by some, perhaps more evident with the rise of AI and our connection via the internet, to fuse the two to provide spiritual and scientific insight. If it can’t be done empirically (proof) with the cold logic of science, I believe that it can be done poetically or metaphorically with the warm intuition of a mystic. Yet, logic itself, if you look into its history, was not meant to be only cold or calculated reason, because it, too, comes from mystical origins. Thanks to Gary Lachman for pointing that out in one of his books by tracing its history.

AI Overview (Google):

Sir Arthur Eddington, a prominent astrophysicist and philosopher of science, held a distinct mystical outlook that deeply influenced his understanding of the relationship between science and religion.

Here’s a breakdown of Eddington’s mystical outlook:

- Quakerism and the inner light

- Eddington was a devout Quaker, a religious tradition that emphasizes the importance of personal religious experience and an inner guiding spiritual force known as the “Inner Light”.

- This Quaker background heavily shaped his understanding of spirituality and influenced his approach to both science and religion.

- He believed that just as in religion, where one seeks guidance from the Inner Light, in science, one should embrace exploration and not be overly concerned with absolute certainty.

- Complementary perspectives

- Eddington saw science and religion as complementary avenues to understanding reality, not opposing forces.

- He believed that science explores the measurable, physical world, while spirituality delves into the unseen, mystical realm.

- For Eddington, both were rooted in fundamental human experiences like beauty, truth, and a deep-seated desire for meaning.

- The limitations of science

- While acknowledging the power of scientific inquiry, Eddington also recognized its inherent limitations.

- He famously stated that physics provides only a “shadow world of symbols,” an abstract representation of reality, and that science cannot fully capture the entirety of human experience, including the spiritual dimension.

- The primacy of mind and spirit

- Eddington proposed that all reality is fundamentally spiritual, not just material.

- He suggested that the physical world perceived through the senses is a construction of consciousness. The ultimate reality, which he sometimes called “mind-stuff,” is a spiritual “background” or “substratum” from which both mind and matter emerge.

- He believed the personal experience of this unseen, spiritual reality is beyond scientific verification and should be valued on its own terms.

- Mysticism as a “faculty of consciousness”

- Eddington believed a “mystical faculty” of consciousness allows individuals to understand a spiritual reality that transcends space and time.

- He viewed this as similar to the act of faith involved in believing that sensory input represents a real external world.

- Just as individuals rely on their senses to understand the visible world, they can rely on inner experience to gain knowledge of the unseen world, according to Eddington.

- Impact and legacy

- Eddington’s attempt to bridge science and religion resonated with many people grappling with the implications of new scientific theories like relativity and quantum mechanics.

- His popular writings made these complex ideas accessible to a wide audience and encouraged a more holistic view of reality that embraced both scientific knowledge and spiritual understanding.

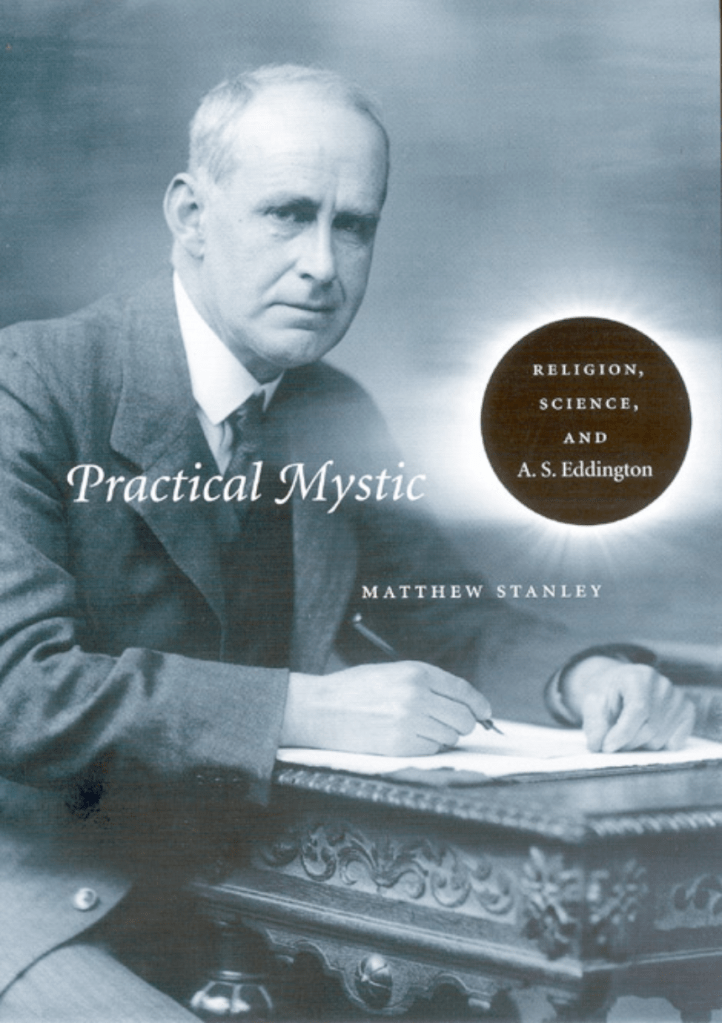

- While some of his philosophical ideas, particularly his “fundamental theory,” were not widely accepted by his scientific colleagues, Matthew Stanley’s book, “Practical Mystic,” demonstrates the lasting relevance of Eddington’s approach to the ongoing dialogue between science and religion.

Goodreads quote:

“Asked in 1919 whether it was true that only three people in the world understood the theory of general relativity, [Eddington] allegedly replied: ‘Who’s the third?” ― Arthur Stanley Eddington.

Sources:

https://philarchive.org/archive/MCKAST-2

// A book I didn’t read, but am interested in reading: