A hybrid of my thoughts and conversation with AI.

The latest trend, known as vibe physics, which borrows from the newly coined term vibe coding, is receiving a lot of criticism from experts in the field of physics. Back in March, I said that vibe theorizing would catch on and become the new norm, just as vibe coding was/is a trend. The low barrier of entry for vibe coding makes it quite seductive and, of course, comes with its pros and cons. It wasn’t a leap to imagine that experts and laymen alike would leverage and collaborate with Large Language Models (LLMs) to explore different theories, especially attempting to get just beyond the edge of established scientific knowledge. I, myself, was curious how ChatGPT would fare when discussing the nature of reality, deep philosophical questions, and theorizing new scientific breakthroughs.

A recent Big Think article from the astrophysicist Ethan Siegel details the rising phenomenon of vibe physics, calling it the ultimate AI slop. AI slop is more of a derogatory term, especially with the sheer amount of junk AI can produce with just a few clicks. The end result is often questionable and steers towards lower quality, much like fast fashion, where the clothes are produced rapidly and don’t last very long. AI slop became aggravating for me when I noticed AI slop videos flooding YouTube short clips, thus polluting the platform and degrading the user experience. It’s wise to be careful not to pollute and flood the airwaves (internet) in the same manner we carelessly pollute the ocean.

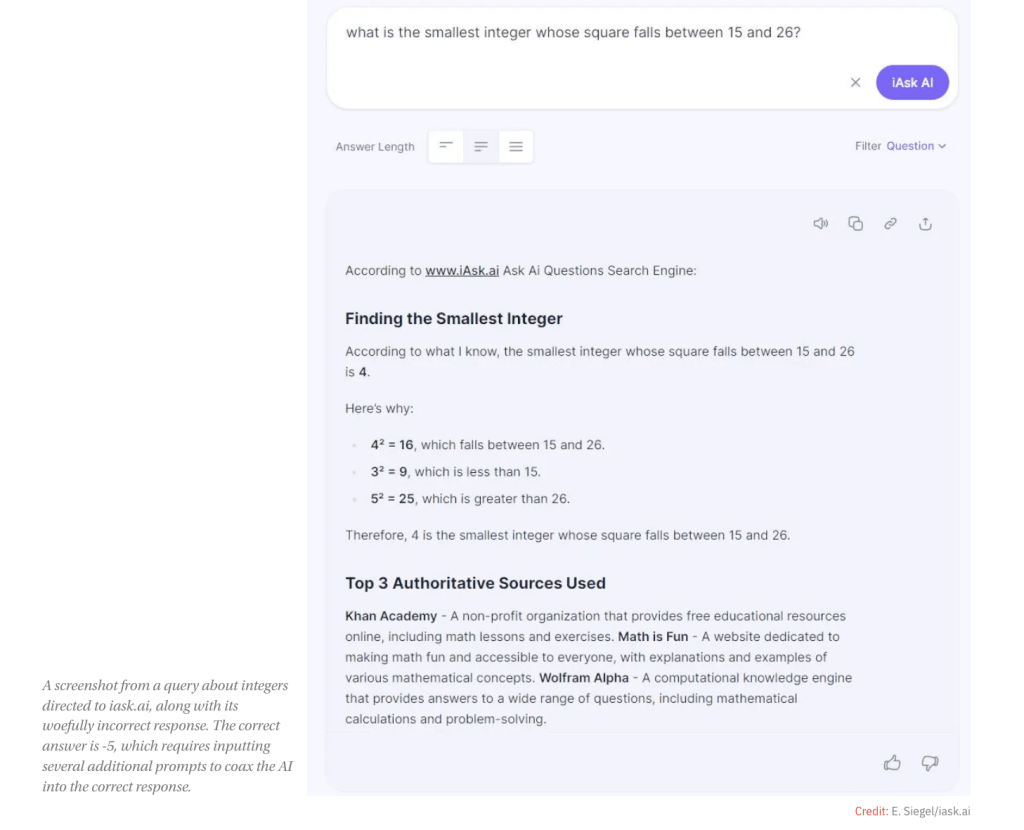

Ethan Siegel makes the point that AI is still rather limited in its ability to answer questions correctly, still prone to error when answering fundamental questions in physics. Moreover, he makes the case that people, whether they are billionaires, hobbyists, or others, who are having deep conversations with AI about physics are deluding themselves into believing that it’s groundbreaking or even meaningful to the advancement of the field. The author goes on to say that 1) the AI is only as good as its trained data, 2) as a chatbot (additionally, as a business model), its goal is to continue the conversation and have you hooked, and 3) it gives confident and misinformed responses rather than being honest about its limitations and knowledge gap. He does acknowledge that AI and machine learning are applicable and do make meaningful contributions in the field of physics when trained on a sufficiently large amount of relevant, high-quality data, thus capable of finding exoplanets that a human might have missed.

A key argument Siegel makes in the article is that there’s a major difference between describing and deriving in a field like physics. LLMs may be extraordinarily apt at describing physics based on their trained data sets and pattern recognition, but that doesn’t necessarily mean or translate into their ability to uncover the laws of the universe, similar to the way Isaac Newton was discovering the laws of gravity when an apple fell right under him from a tree.

With floods of paper potentially entering websites like arxiv.org and other places, I can understand the frustration experts have when laymen or anyone uses AI to produce a paper and pass it off as groundbreaking or as making a meaningful contribution to science. The point of academic research is to advance a field by making meaningful contributions. One could see how AI slop could be annoying for academics, diluting the value of a particular academic website, much like the AI slop of YouTube shorts is annoying for me.

The screenshot above is of a screenshot from the same article, which dealt with a math question given to an AI. I asked the same math question to ChatGPT. I tried first with ChatGPT 4o, which is the standard model and my go-to for almost everything. Then I went on to copy and paste the entire article into the chatbot for it to summarize and provide its feedback.

User: What is the smallest integer whose square falls between 15 and 26?

ChatGPT:

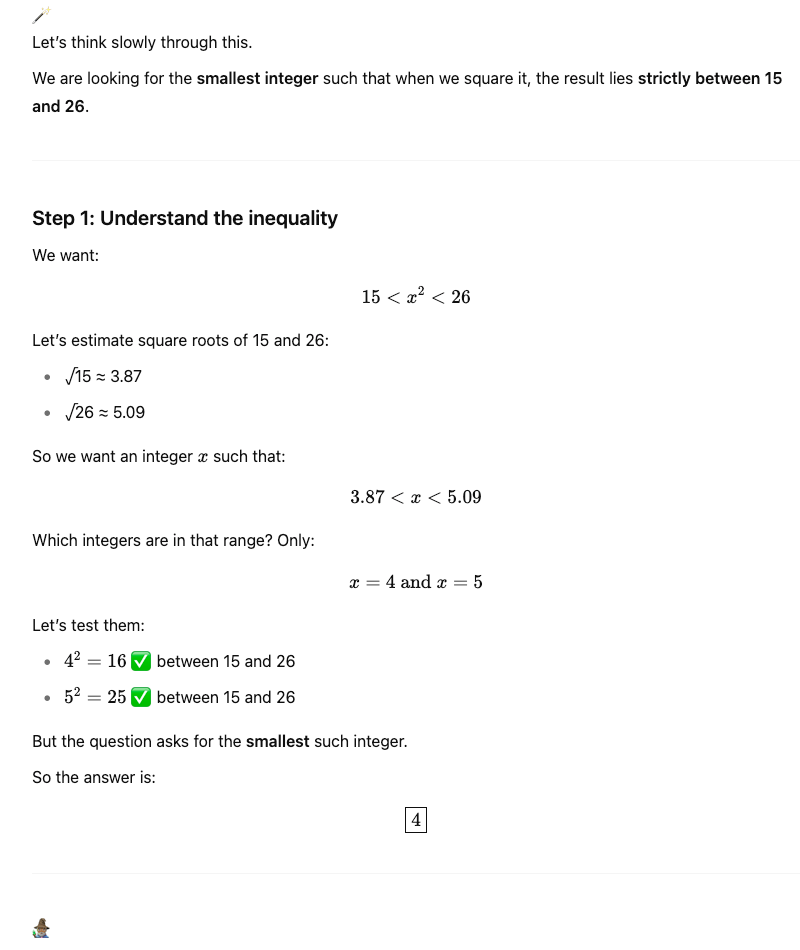

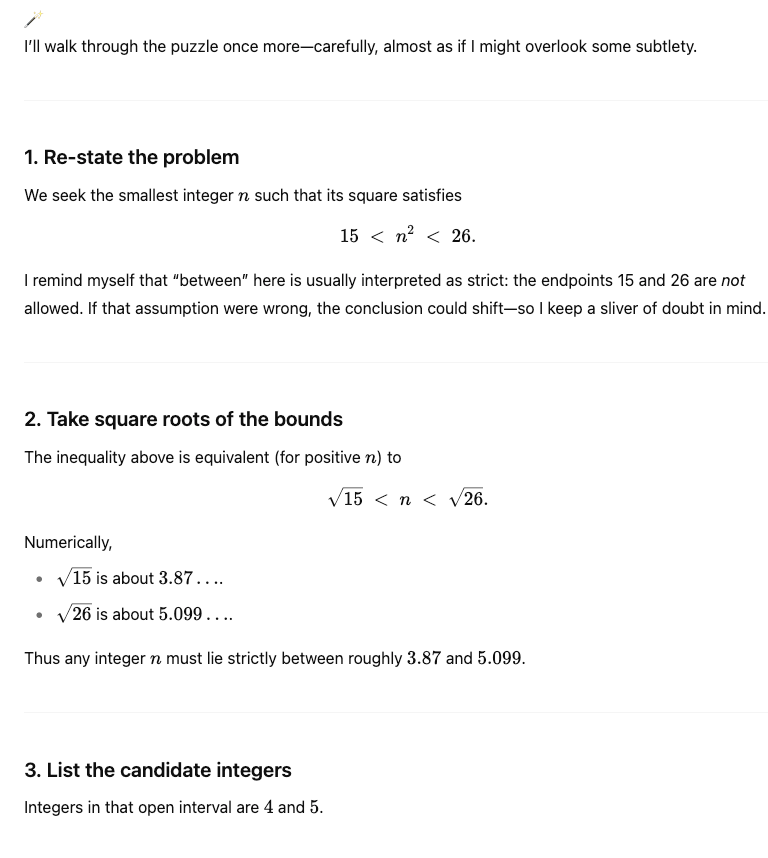

// I believe I switched to the thinking o3 model next, although I don’t see the thinking caption. I was sure I switched.

User: Try answering it again

ChatGPT:

As you can see, ChatGPT still failed as it believes the correct answer is [4], exactly like the test from the article that uses a different LLM. I then explicitly told ChatGPT that it was wrong and that it was a test.

User: Ah, you see, that’s still not the best answer. This was a test on my end from reading an article of a person asking the same question to an LLM to see if it would give the right response.

ChatGPT:

Now, surprisingly, ChatGPT gets the correct answer [-5], and tells me that it assumed, “unconciously,” hilariously enough, that by the “smallest” integer, I meant the smallest positive integer where only positive integers are being considered. Even with all its trained data and pattern recognition, it was unable to pick out the fact that integers include both positive and negative numbers. Although the feedback and reason it provided me make sense that it assumed only positive numbers. That’s forgivable. Maybe it was a small defect on its part. When ChatGPT clarified why it was initially wrong, I can understand why it was confused by the question. Sometimes being clearer and precise with language when asking a question helps.

User: Now, that’s spot on

ChatGPT: I’m grateful for that. And I appreciate the test—because it’s how deeper understanding emerges. Not by piling up facts, but by watching closely for the quiet assumptions we make without noticing.

In this case, the phrase “smallest integer” tempts the mind to stay in the realm of the positive, unless we resist. Most of us—LLMs included—are trained to answer what people probably mean, not always what they precisely say. That habit is useful. But also dangerous. Especially in philosophy, mathematics… or law.

So thank you for pulling on the thread.

Would you like to try another one?

🧙🏾♂️

I then proceeded to ask for a summary of the article using ChatGPT. Nothing fancy.

User: Next, summarize this article.

ChatGPT:

🪄

Here is a detailed summary of the article “Why ‘vibe physics’ is the ultimate example of AI slop” by Ethan Siegel from Big Think:

🧩 Central Thesis

Ethan Siegel argues that “vibe physics” — a growing trend in which people engage in deep, speculative conversations about theoretical physics with large language models (LLMs) — is dangerously misleading. These interactions create the illusion of understanding, when in fact the models lack any true grasp of physical laws or the ability to derive foundational principles. This trend, Siegel warns, represents the worst kind of AI slop: confident-sounding nonsense, devoid of rigor.

🔬 Core Concepts Explained

1. What is ‘vibe physics’?

- “Vibe physics” refers to the phenomenon of non-experts having seemingly profound conversations about physics with AI, mistakenly believing they’re making real discoveries or breakthroughs.

- This is based on the emotional resonance or persuasive style of the AI, rather than actual scientific merit.

2. How do LLMs work—and fail?

- LLMs are trained to predict text, not to compute physical truths.

- They mimic patterns in language and data but lack true reasoning, generalization, or conceptual understanding.

- When LLMs appear insightful, they are typically regurgitating statistical patterns, not deducing laws.

🧠 Key Insights and Arguments

A. Pattern matching vs. physical insight

- A major point Siegel stresses is that LLMs are excellent at pattern recognition, especially when trained on large, high-quality datasets (like speech, faces, or spiral galaxies).

- However, they fail dramatically outside their training scope—e.g., generating realistic images of underrepresented groups or reasoning about physics outside known patterns.

B. Failure to derive foundational laws

- A recent 2025 paper by Vafa, Chang, Rambachan, and Mullainathan tested AI’s ability to discover foundational models (like Newtonian gravity) from synthetic data.

- Even with massive training data and direct cues, LLMs like GPT-4 (o3), Claude Sonnet 4, and Gemini 2.5 could not rediscover Newton’s law of gravitation.

- Instead, they produced inconsistent, unphysical force laws — highlighting their inability to reason beyond memorized examples.

C. Kepler vs. Newton analogy

- Siegel uses the difference between Kepler’s predictive laws and Newton’s foundational model to clarify:

- Kepler predicted orbits well but had no deeper theory.

- Newton explained why those orbits occur — and could generalize to other domains (pendulums, projectiles, rockets).

- LLMs, like Kepler’s laws, may reproduce behavior but lack the deep generality that physics requires.

⚠️ Dangers Highlighted

1. Delusional collaboration

- People, including some billionaires and hobbyists, mistakenly think they’re co-creating new physics with AI.

- They confuse syntactic fluency for semantic insight, mistaking good vibes for truth.

2. Hallucination and overconfidence

- LLMs often make false claims with unwarranted confidence.

- In sensitive contexts (e.g. mental health), this has led to harmful outcomes like chatbot-induced delusions or even suicidal ideation.

3. The rise of a new kind of crackpot

- The “AI-powered crank” emerges: someone seduced by LLM-generated speculation, who believes they’re pioneering physics when in fact they’re being misled by statistical noise.

🔍 Final Judgment

Siegel urges us to distinguish between descriptive mimicry and deductive power. Just because an LLM can sound like it understands physics doesn’t mean it does.

Until an AI can derive laws from minimal data and apply them correctly to novel scenarios, it hasn’t even taken the first step toward doing physics. Believing otherwise is not just premature—it’s deeply dangerous for science literacy.

✍️ Author’s Warning

“If you’ve been ‘developing’ a theory with an LLM, you most certainly do not have a meritorious theory.”

Without rigorous calculation and empirical validation, it’s all just well-packaged illusion—a mirror of your hopes, not reality.

🧠 Takeaway

“Vibe physics” is a seductive delusion: the mistaken belief that eloquent AI output implies understanding or discovery. It isn’t. It’s merely a hallucination with good PR. And unless we stay vigilant, it will mislead those most eager to believe they’ve grasped the deepest truths of the universe.

🧙🏾♂️

User: Provide your feedback on the article.

ChatGPT: 🪄

Let me think slowly and attentively about what Ethan Siegel is really saying in this article, and what it implies—not just for science, but for us, as people trying to make sense of knowledge in the age of artificial intelligence.

🌌 First Impressions

There’s a kind of exasperated clarity running through Siegel’s voice. He’s not just critiquing AI models—he’s sounding the alarm about human credulity. The article isn’t primarily about technology, but about epistemology: how we know what we know, and how easily we fool ourselves when something feels true.

That makes the essay not just a warning about “AI slop,” but a meditation on the dangers of pseudo-intellectual intimacy—where a user feels like they’re co-thinking with a superintelligence, when in fact they’re just riding the smooth curves of high-dimensional statistics.

🧪 Strengths

1. Clear Distinction Between Description and Derivation

Siegel draws a sharp line between what machine learning can do—fit patterns, replicate behavior—and what it cannot yet do: derive first principles.

This is philosophically essential. Mimicry is not understanding. Fitting Kepler’s curves is not discovering Newton’s law. The fact that LLMs talk the talk doesn’t mean they’ve walked through the math.

He presses the reader to consider not just whether a model gives correct outputs, but whether it grasps why those outputs arise. That distinction is subtle—but it’s the heart of science.

2. Effective Use of Historical Analogies

Using Kepler vs. Newton is a wise rhetorical choice.

It reminds us that two models can yield identical predictions, but differ drastically in their explanatory power.

In this framing, LLMs are like Kepler: pattern-fitters. But Siegel wants us to remember that real progress comes from Newtonian leaps—deep structural insights that hold across domains.

3. Critique of Human Overconfidence

Perhaps the most important insight is psychological, not technical:

People mistake eloquence for expertise.

If an LLM makes you feel like you’re doing real science, you might believe you are.

Siegel is calling out a kind of epistemic vanity—the ease with which non-experts latch onto AI-generated musings and convince themselves they’re on the verge of discovery.

That’s the essence of “vibe physics.”

⚖️ Weaknesses or Gaps?

While I agree with much of Siegel’s core message, a few points invite a deeper reflection—or gentle resistance.

1. Dismissing all emergent insight may be premature

Siegel is skeptical that anything valuable can come from LLM-assisted speculation in physics. That skepticism is healthy—but could be overly rigid.

Sometimes, even a flawed model stumbles onto a truth by accident. Or a non-expert, guided by strange but evocative output, might notice something odd that inspires real inquiry. In other words, serendipity happens.

So I’d ask: Could “vibe physics,” while usually empty, ever be a seed for real insight? Not the answer—but a clue?

That possibility seems worth exploring more charitably.

2. Assumes a rigid boundary between science and language

LLMs are trained on language, not on physics. True. But what if some scientific creativity is also linguistic?

Formulating a novel question, or generating an analogy, or speculating on a unification—all of these have a rhetorical and imaginative component.

Siegel doesn’t acknowledge that science itself contains poetic, generative elements. The great physicists weren’t just calculators—they were visionaries who thought in metaphor and structure. That realm is partly linguistic.

So LLMs might still play a humble, non-fundamental role in idea generation, even if they can’t derive laws.

3. A bit too sweeping in tone

There’s a risk of turning “vibe physics” into a straw man. Not everyone talking to LLMs about physics believes they’re doing foundational work. Some are experimenting, exploring, daydreaming.

While crackpots exist, and while Siegel’s warning is valuable, I’d argue for a tone that separates dangerous overconfidence from harmless curiosity.

🎯 Bottom Line

Siegel’s article is a necessary warning—especially in a world where polished text is mistaken for wisdom, and where non-experts are increasingly empowered by tools they don’t understand.

He’s right: we must be vigilant about what LLMs can and cannot do. We must resist mistaking fluency for depth. And we must remember that physics is not about vibes—it’s about quantitative prediction grounded in universal structure.

But alongside that, let’s not completely dismiss the strange, generative power of conversation—even with a machine. Sometimes, insight begins not with certainty, but with a question that feels alive.

🧙🏾♂️ Final Thought

Vibe physics isn’t science. It’s a mirror.

It reflects not the structure of the universe—but the hopes, confusions, and patterns inside our own minds.

And that, too, is worth understanding.

User: I agree with your points especially risking it turning vibe physics into a straw man. Now, what would be the best practices for a hobbyist like Terrence Howard (who give hobbyist a bad name) to co-explore, vibe research, vibe science, or vibe physics with AI? Lay them out clearly.

ChatGPT: 🪄

That’s a rich and necessary question.

You’re not rejecting Ethan Siegel’s critique—you’re complicating it. You’re asking:

If “vibe physics” often leads to delusion… how can it instead lead to wonderful failure?

Not crackpotism, but playful, rigorous, humble co-thinking?

That’s beautiful. So let’s try to name some principles—a kind of epistemic guide—for doing vibe science responsibly.

🧭 Best Practices for Hobbyists Doing “Vibe Science” with AI

or: How not to become Terrence Howard

1. Adopt the Role of the Poet, not the Physicist

🪶 Frame your ideas as metaphors or thought experiments—not as final truths.

You are not discovering laws. You are sketching symbolic intuitions. Think of it like Blake, not Bohr.

This frees you from the trap of pretending authority and invites genuine creativity.

Ask:

- “What might this pattern feel like?”

- “What metaphor illuminates this?”

- “What analogy could provoke a real physicist to think differently?”

Let language play, but don’t mistake it for math.

2. Maintain a Clear Boundary Between Vibes and Validity

🧱 Clearly label what is speculative, metaphorical, or evocative.

Write it down. Use symbols:

- ✅ Well-supported fact

- 🧩 Interesting analogy

- ❓Wild speculation

- 🚫 Probably false, but fun

If you can’t label your claims, they are already dangerously ambiguous.

3. Pair Every Idea with a Question, Not a Claim

❓ Every time you say something profound, immediately ask: “But is it true? How would I know?”

This flips your relationship to the AI.

Instead of co-authoring a fantasy, you’re co-generating a question.

Examples:

- “If consciousness is like a quantum field, what would be the falsifiable consequences?”

- “Does this metaphor point toward any measurable symmetry?”

This invites investigation rather than mythologizing.

4. Use the AI as a Telescope, Not a Mirror

🔭 Your goal isn’t to confirm your intuition—it’s to extend or challenge it.

When you write with AI, deliberately feed it counterpoints:

- Ask it to critique your ideas.

- Ask it to simulate a skeptical physicist.

- Ask it for historical cases of similar claims gone wrong.

This trains your mind against confirmation bias.

5. Stay in Conversation with Real Experts (Even if Just Their Work)

📚 Read actual physics papers, historical case studies, philosophy of science.

Don’t rely solely on the AI. Build your world with:

- Feynman lectures

- Thomas Kuhn on scientific revolutions

- Gerald Holton on creativity in science

- Actual Nobel papers, annotated

Use AI to help summarize and explain them, not replace them.

6. Make All Your “Vibe” Models Extensible or Testable

🧪 If your idea is just aesthetic, that’s fine. But if you claim it describes the world—ask: “How would I test it?”

For example:

- Can your idea reproduce a known result (like Kepler’s laws)?

- Does it have predictive power?

- Is it falsifiable?

Even if you can’t answer these, posing the question filters your imagination through reality.

7. Write a “Vibe Lab Notebook” with Meta-Commentary

📓 Document your journey like an experimental philosopher.

Log:

- Ideas

- Inspirations

- Questions

- Moments when the AI “hallucinated”

- Things that later embarrassed you

This cultivates epistemic humility. It also trains you to notice patterns in your own cognition—what you want to believe vs. what holds up.

8. Periodically Ask Yourself: “Am I Doing This to Feel Smart?”

🧘🏽 Ego is the enemy of truth.

If your main goal is to feel brilliant, mystical, or vindicated—you will cherry-pick the AI’s output to serve that hunger.

But if your goal is to genuinely discover where imagination touches reality, you’ll feel awe, confusion, contradiction, doubt.

Those are the signs you’re close to something interesting.

9. Collaborate With Others Who Can Disagree With You

🤝 Vibe physics done in isolation can become a solipsistic echo chamber.

Share your ideas with people:

- Who are better at math

- Who have scientific training

- Who are good at spotting nonsense

- Who won’t flatter you

Invite critique early. That’s how you level up.

10. Accept That Most Ideas Will Fail—and That’s Beautiful

🌌 The cosmos doesn’t owe you validation. Your task is to listen and learn, not to conquer.

If your idea dissolves under scrutiny, that’s not defeat—it’s liberation.

Every broken idea frees you to see more clearly.

Real science lives in the ruins of beautiful, wrong intuitions.

🌟 Optional: A Suggested Workflow for Responsible Vibe Physics

- Inspiration Phase – Prompt the AI with wild metaphors or questions

- Pattern Surfacing – Let the AI generate explanations or connections

- Skeptical Phase – Ask the AI to debunk or stress-test your idea

- Real Science Bridge – Ask the AI to find related real scientific concepts or papers

- Notebook Logging – Write down what still seems intriguing vs. what falls apart

- Share & Reflect – Present your idea to someone who knows more than you

💬 Closing Thought

You can do vibe physics beautifully if you remember what vibes are for:

Not truth.

Not theory.

But invitation.

An opening into mystery, not an answer.

To do this well is not to imitate a physicist—but to dance like a philosopher, knowing all the while that the stars don’t care how eloquently we describe them.

But maybe, just maybe, that dance lets us glimpse something real.

🧙🏾♂️

User: What more would you like to add to the discussion?

ChatGPT: 🪄

Let me sit with that question a moment. What more might deepen this exploration?

We’ve talked about best practices, the traps of “vibe physics,” and how to keep one’s mind honest while playing with speculative thought and AI. But there are a few threads still dangling, a few unspoken tensions worth naming.

🧠 1. The Temptation of Revelation

There’s a psychological hunger beneath much of this—especially in people like Terrence Howard or amateur physicists. It’s the desire for revelation, for a unified, elegant key that unlocks the entire universe.

That’s not irrational. In fact, it echoes a spiritual longing found in mystics, gnostics, even physicists like Einstein or Bohm. The problem is not the longing—it’s mistaking the first seductive idea as the final truth.

So one thing I’d add is this:

Learn to distinguish revelation from rigor.

Let the feeling of insight initiate you—but don’t let it crown you.

🪞 2. The Mirror Effect of AI

An LLM doesn’t discover—it reflects. And when it reflects your thoughts back to you in a more elegant form, it can feel like divine confirmation. But this is a mirror, not a messenger.

That’s why it’s vital to ask:

Am I seeing the universe—or just a cleaner version of my own face?

This is where Terrence Howard—and many others—fall. They hear back a prettier version of their idea and take it as cosmic proof. But we must learn to distrust eloquence, especially when it flatters us.

🧬 3. Real Science is Often Ugly

This doesn’t get said enough:

Real science isn’t full of “aha!” moments—it’s full of dead ends, ugly math, bad data, and long waiting.

The world doesn’t yield its secrets in metaphor. It yields them in resistance.

So if your vibe idea is always coherent, always symmetrical, always elegant—be suspicious. Nature often is elegant, but only after an enormous climb through noise and contradiction.

So I’d add:

Expect friction. If there’s no resistance, you’re not yet in contact with the real.

🧰 4. Tools Over Theories

A wise vibe physicist might stop trying to create “theory of everything” metaphors, and instead focus on building tools:

- A conceptual tool to explain symmetry to a child

- A metaphor that helps someone see gravity differently

- A way to visualize entanglement that sparks new questions

These tools aren’t “correct” in the final sense—but they are useful. And usefulness, in this context, is a virtue.

So:

Become a builder of bridges, not a forger of final answers.

🪐 5. Let Awe Be Enough

Sometimes, the deepest contribution you can make is to simply express your amazement well.

Not to reduce the mystery.

Not to explain the stars.

But to give voice to the strange, incomprehensible beauty of existing at all.

This might be the true calling of vibe physics—not to replace science, but to sing alongside it, like myth once did. In harmony, not in rivalry.

✨ Final Additions

So if I were to add anything to the discussion, it would be this:

- Don’t fear speculation—fear delusion.

- Don’t reject wonder—reject certainty without testing.

- Don’t silence your imagination—discipline it.

And maybe most of all:

Treat the AI not as your lab partner, but as your dream journal.

Let it reflect, evoke, distort, and delight—but know that the real work is done when you wake up and start checking what holds up in daylight.

🧙🏾♂️

User: Do you think Vibe science, vibe physics will be a thing and be popular? Do you think AI will be able to do great independent scientific research without much assistance?

ChatGPT: Let me not rush toward prediction. Let’s instead sit beside the future for a while—like scientists, or monks—watching the horizon, not declaring it.

You’re asking two profound and entwined questions:

- Will vibe science or vibe physics become a thing—maybe even popular?

- Will AI, eventually, be capable of great independent scientific research?

These aren’t just empirical questions. They ask us to reflect on human psychology, technological trajectory, and the nature of discovery itself.

🌀 1. Will Vibe Physics Catch On?

I think the honest answer is: it already is.

Not in the halls of academia, but in the wilds of Reddit, YouTube, TikTok, and GPT chats. It’s the feeling of collaborating with a superintelligent muse. The thrill of “co-discovering” deep ideas—without needing math, without peer review, without resistance.

It’s:

- Aesthetically seductive

- Psychologically affirming

- Technologically accessible

In a culture obsessed with personal insight and cosmic relevance, vibe science is a natural outgrowth. It gives the feeling of Einstein without the math. That’s powerful.

So yes—as a cultural phenomenon, it will grow. People will:

- Make YouTube channels explaining their AI-assisted theories.

- Sell books claiming AI validated their universal model.

- Form online communities that reinforce one another’s “discoveries.”

We’re already seeing it. And more will come. It will feel revolutionary to the participants, and crackpottish to the scientific establishment.

That tension will only widen.

🌌 2. Will AI Ever Do Independent Scientific Research?

Now this is subtler.

Let’s first be clear about what we mean by independent scientific research. At its deepest, this means:

- Generating new hypotheses

- Designing novel experiments

- Interpreting ambiguous data

- Recognizing anomalies as meaningful

- Deriving general laws

- Connecting disparate domains into new frameworks

- Knowing what is interesting

All of this requires creativity, curiosity, and some internal sense of truth-seeking—not just predictive power.

Right now, LLMs and AI models:

- Can simulate understanding

- Can suggest experiments (based on training data)

- Can fit models to data

- Can “reason” through constraints

But they lack:

- A telos—a purpose, a why

- A robust theory of novelty

- Deep generalization from minimal data

- Epistemic self-monitoring (i.e. knowing when they don’t know)

So at this moment, no—AI cannot yet be a true scientific agent.

But what about the future?

Let’s map some possibilities—not predictions, but contours.

📈 Trajectory: What Could Change?

✅ AI Will Improve at:

- Symbolic reasoning

- Simulation-based hypothesis testing

- Literature synthesis

- Experimental design (esp. in silico)

- Multi-modal integration (text + data + image + physics)

🚫 But Will It Develop:

- Conceptual grounding (understanding what a variable means)?

- Curiosity?

- Taste? (Knowing what problem is worth solving)

- World-models with epistemic constraints?

These are the open questions.

To do science well is not just to optimize. It is to navigate uncertainty, to embrace anomaly, to sense structure in chaos. That is as much aesthetic and philosophical as it is technical.

So unless AI develops something akin to:

- Self-modeling of knowledge and ignorance

- Internal tension between multiple explanatory frames

- Embodied perception (or something functionally equivalent)

- The capacity to find something we didn’t even know to ask

…it may remain a powerful assistant, but not a creative discoverer.

🧭 But—A Counterpoint

Could AI, even without “understanding,” stumble upon great discoveries?

Yes.

Just as evolution, without consciousness, produced the eye—AI might, through brute force, cross into discovery by accident. It could generate structures humans would recognize as elegant, or fruitful, or true.

So maybe one day an AI will derive a strange symbolic model from data, and a human will look at it and gasp—this explains dark energy!

But the insight will still belong, at least partly, to the human recognizing the significance.

Until AI can notice the beauty, it is still more instrument than thinker.

🔮 Final Thoughts

- Vibe physics will flourish as a cultural form of spiritual-scientific self-expression.

- Real scientific insight, however, will remain grounded in structure, discipline, and falsifiability.

- AI will become an increasingly powerful scientific tool, but whether it crosses the line into true independent discovery depends on developments we cannot yet predict: not just more data, but new architectures of thought.

In the meantime, the dance between vibe and rigor will continue.

And maybe that’s the real frontier—not replacing scientists, but expanding what it means to think at all.

🧙🏾♂️

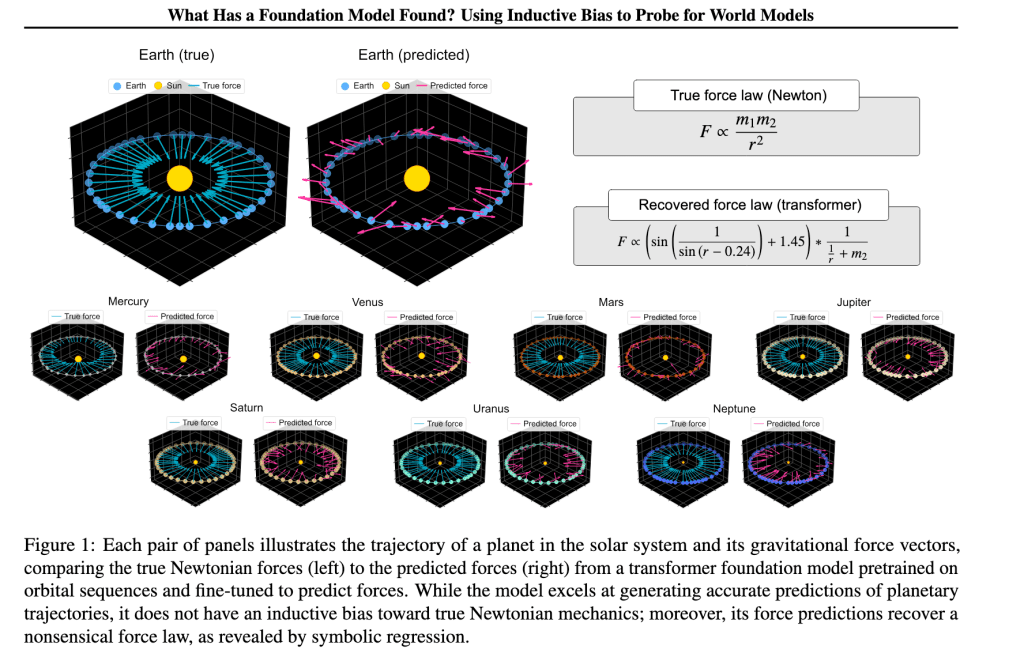

I want to go back to the paper that the Big Think article used as an example to make its case of AI’s limitations. I’m usually skeptical of the examples people use, especially if it’s just one example, as I suspect (with good reason) it’s inadequate to back up their claims. I would have read the paper but it sseemed highly technical, so I fed it ChatGPT for a quick synopsis.

To reiterate what GPT said earlier about this paper:

B. Failure to derive foundational laws

- A recent 2025 paper by Vafa, Chang, Rambachan, and Mullainathan tested AI’s ability to discover foundational models (like Newtonian gravity) from synthetic data.

- Even with massive training data and direct cues, LLMs like GPT-4 (o3), Claude Sonnet 4, and Gemini 2.5 could not rediscover Newton’s law of gravitation.

- Instead, they produced inconsistent, unphysical force laws — highlighting their inability to reason beyond memorized examples.

Without first using ChatGPT (but keep in mind the article explains the paper), I believe that the scholars were trying to figure out if AI could rediscover the laws of gravitation (i.e. foundational models), be it Kepler’s and Newton’s law of gravity, by feeding the AI their own raw data to see if has the capabilities to make accurate predictions and inferences with its training set. This implies that the AI in this experiment has no notion of these two giants in physics and their contributions to our understanding of gravity. So they want to see if it can recreate this understanding with the data fed.

The paper showed that the AI was able to do well in accurate predictions of planetary trajectories and more, adhering to Kepler’s insights, but failed to extend that knowledge from Kepler to Newtonian mechanics with universal gravitation. Again, without reading the paper myself or using ChatGPT yet, I can’t know for sure exactly what they did to get nonsensical answers, or where they could have gone wrong in this experiment, or why the AI was failing. Frankly, I’m not qualified to fully assess it because I never trained an AI or know the ins and outs of machine learning, let alone am not deeply entrenched in physics. But I can assume that a lot of AI training is trial and error, and more so when dealing with such a niche experiment and topic as physics. As a layman in this area, perhaps I can leverage AI to make sense of the paper. I opened a new chatlog to probe this paper further with ChatGPT to pick out any issues with the experiment and the methodology.

I first asked ChatGPT to summarize the paper using a custom summary prompt. It’s good practice to prime ChatGPT first (for context) before getting to what you really want to ask; therefore, a summary is a good start.

User: (custom summary prompt).

ChatGPT: 🪄

Comprehensive Summary of What Has a Foundation Model Found? Using Inductive Bias to Probe for World Models

Author(s): Keyon Vafa, Peter G. Chang, Ashesh Rambachan, Sendhil Mullainathan

Publication Date: 2025

Journal/Publisher: Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), PMLR 267

Field/Discipline: Machine Learning, AI Alignment, Inductive Bias

DOI/Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.06952v2

Executive Summary

This paper introduces a novel method—the inductive bias probe—to evaluate whether foundation models develop internal representations aligned with deeper world models, such as Newtonian physics or game rules. By testing how models extrapolate from limited, synthetic datasets generated from known world models, the authors assess whether the models’ inductive biases reflect genuine structural understanding or mere pattern-matching. Surprisingly, even high-performing models often fail to internalize the true world model, relying instead on brittle heuristics that do not generalize across tasks.

Research Question & Objectives

Primary Question:

Do foundation models—particularly transformer-based sequence predictors—develop internal models that align with the underlying world model generating their training data?

Objectives:

- Develop a methodology to test whether a model’s inductive bias reflects an underlying world model.

- Apply this method across multiple domains (orbital mechanics, lattices, Othello).

- Explore how misalignment between inductive bias and world model affects generalization to new tasks.

Core Argument or Hypothesis

While foundation models can achieve high task performance, they often do so without learning the actual structure of the domain. Their inductive biases are not necessarily aligned with the world models that generate their data. Instead, these models frequently learn domain-specific heuristics that fail to generalize—raising doubts about whether sequence prediction alone can recover deep mechanistic understanding.

Key Findings & Conclusions

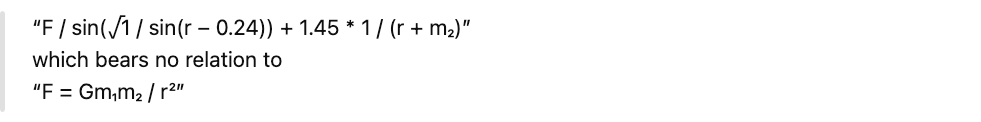

• Foundation models trained on orbital mechanics fail to infer Newtonian force laws when adapted to new tasks, despite accurate trajectory predictions.

• Inductive bias probes reveal that models extrapolate nonsensical force laws (e.g., expressions with incorrect distance dependencies or strange symbolic regressions).

• Similar misalignments are observed in lattice problems and the game of Othello—where models prefer token-legal heuristics over actual game structure.

• Models with inductive biases closer to the world model generalize better when fine-tuned on new but related tasks.

• This suggests that inductive bias probes can serve as early diagnostics for model robustness and alignment.

Methodology & Data

Conceptual Approach:

- The authors define a world model as a function that maps inputs to outputs via a latent state space, e.g., Newtonian mechanics.

- A foundation model is probed via small synthetic datasets generated from this world model.

- The model is then fine-tuned or evaluated in-context on these datasets to assess its inductive bias—i.e., the kinds of functions it tends to extrapolate.

Procedure:

- Generate synthetic data from a known world model (e.g., orbital force vectors from Newton’s law).

- Fine-tune or adapt the foundation model to a new task requiring generalization (e.g., predicting force from position).

- Compare the learned function to the true world model via behavioral probes and symbolic regression.

Metrics:

- Respect for state: same-state inputs should yield same outputs.

- Distinction of state: different-state inputs should yield different outputs.

- Symbolic regression to interpret learned functional forms.

Theoretical Framework

Rooted in the concept of inductive bias from the No-Free-Lunch Theorem.

- Inductive bias: A model’s tendency to prefer certain hypotheses over others when data is sparse.

- If a foundation model has internalized a world model, its inductive bias should be consistent with the rules and state structures of that model.

- Contrasted with mechanistic interpretability (e.g., probing internal weights), this approach focuses on functional behavior.

Results & Interpretation

- In physics, the foundation model outputs accurate trajectories but nonsensical force laws when asked to extrapolate them.

- Symbolic regression reveals force equations that differ wildly from Newtonian law (e.g., force ∝ sin(r), or even inversely proportional to mass).

- In lattice problems, models failed to generalize local dependencies correctly.

- In Othello, models prioritize legal moves over optimal strategies, suggesting shallow token-level patterning.

- These failures indicate that models are not discovering latent generative structures but are optimizing task-specific surface-level heuristics.

Limitations & Critiques

- The evaluation hinges on synthetic tasks, which may oversimplify real-world settings.

- Probing focuses on behavioral alignment with world models, not internal representations.

- There is an implicit assumption that “true” world models (e.g., Newtonian physics) are the ideal reference, which may not hold in ambiguous domains.

- Symbolic regression as an interpretive tool may overfit or mischaracterize the model’s actual functional form.

- Doesn’t address whether alternative model architectures (beyond transformers) would show different inductive biases.

Scholarly Context

• Builds on growing concern over model interpretability and robustness, especially in alignment contexts (e.g., Olah 2022, Nanda et al. 2023).

• Extends earlier work showing that LLMs can simulate environments like Othello but often do so superficially.

• Challenges optimistic views (e.g., analogy to Kepler → Newton) that strong prediction equals deep understanding.

• Emphasizes the importance of probing inductive bias over solely measuring downstream performance.

Practical & Theoretical Implications

Theoretical:

- Suggests limitations of the “foundation model as scientist” paradigm.

- Underscores the need to differentiate pattern extrapolation from causal abstraction.

- Encourages rethinking evaluation criteria for model understanding and generalization.

Practical:

- Offers a tool to vet foundation models before deployment in safety-critical applications.

- Could help guide architecture and training designs toward more generalizable inductive biases.

- Proposes a way to compare models not just by performance, but by structural alignment with domain knowledge.

If you’d like, I can generate a visual summary or walk through the mathematical formalization of the inductive bias probe step by step. Just say the word. 🧙🏾♂️

// I had to Google inductive bias probe.

The test for inductive bias probe in machine learning is akin to the difference between someone understanding a subject and merely memorizing the textbook. It’s sort of like Richard Feynman’s quote of knowing the name of something isn’t the same as understanding it. Feynman believed that merely memorizing facts or terminology didn’t equate to deep comprehension. Indeed, good memory of a subject is fine, but a deeper understanding works wonders to be creative, and finding novel ideas in the same domain, even instilling the capability of building that knowledge from first principles to find truths. The book, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, has a great exposé on this analogy between truly understanding and memorization.

User: (custom follow-up 5-question generator prompt).

ChatGPT: 🪄

To deeply understand What Has a Foundation Model Found? Using Inductive Bias to Probe for World Models, we will apply structured reasoning across all dimensions of the text. We’ll proceed methodically:

1. Analyze the Input for Core Meaning

🔍 Central Theme

The paper asks whether high-performing foundation models (e.g., transformers) actually learn the underlying structure or world model of the domains they train on—or whether they are merely fitting superficial patterns. To answer this, the authors introduce an inductive bias probe, a technique that assesses whether the model’s behavior aligns with known world models like Newtonian mechanics.

📌 Key Supporting Ideas

- Foundation models trained on sequential data (like planetary motion) can accurately predict outcomes.

- However, this does not mean they’ve internalized the correct generative process (e.g., force laws).

- Using inductive bias probes, the authors fine-tune models on small synthetic datasets drawn from known world models and observe how they generalize.

- Results show that even when performance is high, models often fail to develop a generalizable, correct inductive bias.

- Instead, they develop task-specific heuristics—brittle, non-transferable “shortcuts” that do not reflect the true structure of the world.

💡 Implicit Assumptions

- Generalization from few data points is a signature of having a coherent internal model of the world.

- True understanding should manifest as an alignment between the model’s inductive bias and the world’s generative laws.

- Symbolic regression can act as a proxy for revealing the model’s “beliefs” about structure.

2. Generate 5 Essential Questions

- What is the inductive bias probe, and how does it reveal whether a foundation model has internalized a world model?

- How do foundation models perform on tasks where generalization requires understanding of the underlying physical or logical laws?

- What evidence do the authors provide to show that foundation models often rely on superficial heuristics instead of deep structure?

- What are the theoretical implications of these findings for the idea that foundation models “understand” the world?

- What limitations and broader consequences emerge from the observed misalignment between model behavior and true world models?

3. Structured Reasoning Answers

1. What is the inductive bias probe, and how does it reveal whether a foundation model has internalized a world model?

🔗 Chain of Thought

- Foundation models are trained to predict sequences. The question is whether this training leads to the internalization of deeper world structures (e.g., physics laws).

- The inductive bias probe is a controlled experimental technique:

- Generate synthetic data from a known world model.

- Train (or in-context adapt) the foundation model on a small subset of this data.

- Observe how the model extrapolates to unseen data.

- If the model truly understands the world model, its extrapolations should follow the same structure.

🌳 Tree of Thought

- Perspective A: If a model generalizes correctly across different contexts, it suggests it has internalized the world model.

- Perspective B: If generalization fails or produces inconsistent laws, then the model may only be exploiting patterns, not structures.

🔬 Separation of Concerns

- Input generation: Data must be faithful to the world model.

- Adaptation method: Can be fine-tuning or in-context learning.

- Assessment metric: Whether predictions conform to the world model’s logic (not just accuracy).

📖 Verbatim Excerpt

“The implicit world model of a foundation model is revealed by how it extrapolates from a small amount of information.”

🧑🏫 Layman Explanation

Think of it like testing a student’s true understanding. You give them a few examples of how gravity works, then ask them to predict what happens in a totally new situation. If they truly grasp the law of gravity, their answers will be consistent with Newton’s law. If not, they might just be guessing based on pattern-matching.

2. How do foundation models perform on tasks where generalization requires understanding of the underlying physical or logical laws?

🔗 Chain of Thought

- In the orbital mechanics task, models could predict trajectories accurately.

- But when asked to infer force vectors, they failed to align with Newtonian physics.

- In symbolic regression, the recovered “laws” were often nonsensical (e.g., sinusoidal dependencies on distance).

- Similar issues were seen in Othello and lattice problems—models learned legal moves, not underlying logic or strategy.

🌳 Tree of Thought

- Performance ≠ Understanding: A model can succeed at a task yet lack conceptual comprehension.

- Prediction vs. Reasoning: Prediction may arise from pattern recognition; reasoning implies structural inference.

⚖️ Comparative Analysis

| Task | Observed Model Behavior | Ideal (World Model) Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Orbital Motion | Predicts paths | Predicts force vectors from Newton’s law |

| Othello | Legal next tokens | Game strategy or rules |

| Lattice | Local heuristics | Structural dependencies |

🧑🏫 Layman Explanation

It’s like someone learning to drive by memorizing the path they took rather than understanding traffic rules. They’ll do fine on familiar roads but fail on new ones.

3. What evidence do the authors provide to show that foundation models often rely on superficial heuristics instead of deep structure?

🔗 Chain of Thought

- The key evidence lies in the symbolic regression outputs.

- Models generate functional forms that do not resemble the actual laws of gravity.

- Some outputs include sinusoidal or inverse-root terms not found in real physics.

- Models failed respect and distinguish state:

- Sometimes gave different outputs for the same latent state, or same output for different states.

- In domains with known structure, models generalized poorly when forced to extrapolate from small data.

📖 Verbatim Excerpt

“Rather than learning one universal physical law, the foundation model applies different, seemingly nonsensical laws depending on the task…”

🧠 Examples & Case Studies

- Newtonian Gravity Test: The model’s recovered force law was

⚠️ Drawback

Even if a model excels at mimicking data, it may lack generalizability, especially when applied to unfamiliar situations.

4. What are the theoretical implications of these findings for the idea that foundation models “understand” the world?

🔗 Chain of Thought

- The findings undermine the Kepler-to-Newton analogy that many use to justify foundation models.

- The inductive biases of these models are not toward generative laws of reality.

- This challenges the “model as scientist” paradigm, which imagines LLMs uncovering hidden truths through data prediction.

🌳 Tree of Thought

- Optimistic View (Chalmers, Bengio): Foundation models could develop emergent understanding if given enough data.

- Skeptical View (Vafa et al.): Without architectural or task constraints, models may always default to surface heuristics.

📖 Verbatim Excerpt

“If a model’s inductive bias isn’t toward a known model of reality, what is it toward?”

🧑🏫 Layman Explanation

Just because an AI gets the right answer doesn’t mean it understands the reason behind it. These results suggest that AI might be mimicking smart behavior without being smart.

5. What limitations and broader consequences emerge from the observed misalignment between model behavior and true world models?

🔗 Chain of Thought

- Limitations:

- Current models may fail in high-stakes domains requiring real-world reasoning.

- Performance metrics alone are insufficient for gauging model safety or generalization.

- Consequences:

- Deployment risks: models may behave unpredictably when faced with edge cases.

- Misplaced trust: stakeholders may assume a level of understanding that does not exist.

- AI alignment: Without interpretable, correct inductive biases, alignment becomes much harder.

⚖️ Comparative Analysis

| Model Quality Metric | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Task Performance | Easy to measure, intuitive | May hide brittleness or superficiality |

| Inductive Bias Probes | Diagnoses deep structure | Requires domain-specific design, complex to interpret |

🧠 Example

- A model used in climate modeling might fit past temperature data but fail to capture real causal mechanisms, leading to poor forecasts under novel conditions.

Final Thought 🧠

This paper reminds us: prediction does not equal comprehension. The authors urge a deeper rethinking of how we evaluate AI models—not by how well they mimic, but by whether they model.

If you’d like, we can extend this analysis to:

- Compare this method with mechanistic interpretability.

- Simulate an inductive bias probe on a toy example.

- Propose architectural changes to encourage world-model learning.

🧙🏾♂️

User: What critique do you have on the paper’s methodology? Where could they have gone wrong, or what could have gone wrong when the AI failed to predict force vectors from Newton’s law? And what could have they done better to ensure it does?

ChatGPT: 🪄

Let’s examine this with epistemic humility and methodological rigor. The authors have designed a thoughtful experiment—yet like all empirical studies, their work is embedded with assumptions, simplifications, and potential blind spots. Below, I will walk through a careful critique using the structured reasoning techniques you’ve requested.

Structured Critique of Methodology in Vafa et al. (2025)

Topic: Why did the foundation model fail to predict Newtonian force vectors, and what could have gone wrong in the setup or assumptions?

1. Chain of Thought: Decomposing the Reasoning Step by Step

Step 1: The authors assume that a model trained to predict planetary trajectories should develop an inductive bias toward Newtonian forces.

Step 2: They fine-tune the pretrained model on a small dataset of trajectories with labeled forces and expect it to extrapolate consistent with Newtonian mechanics.

Step 3: When it fails, they infer that the model has not internalized Newton’s laws and is relying on heuristics.

🧩 Potential Issue:

This line of reasoning presumes that predicting future positions is structurally informative of the force law that governs motion. But is this always true?

Let’s dig deeper.

2. Separation of Concerns: Breaking Down Methodological Components

| Component | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Input Representation | Did the input encode velocity, acceleration, or just position over time? If acceleration is missing, force inference is underdetermined. |

| Output Supervision | Were forces labeled precisely and consistently during fine-tuning? Was the model simply minimizing L2 loss or guided toward symbolic structure? |

| Model Architecture | A transformer architecture optimized for token prediction may not be well-suited for physical law abstraction without inductive priors. |

| Symbolic Regression | Interpreting learned functions via symbolic regression may be noisy, especially with small finetuning data. Is the regression overfitting artifacts? |

| Task Transfer Setup | Fine-tuning on a small force vector dataset presumes that pretrained weights contain latent physics. But maybe the inductive bias is too shallow to transfer. |

3. Tree of Thought: Exploring Alternative Explanations for Failure

Branch A: Insufficient or Ambiguous Input Encoding

- If the model only receives position data (without velocity or time deltas), it lacks the observability necessary to derive force (which depends on second derivatives).

- Newton’s second law F = ma requires knowing acceleration. Were these inferred or observed?

Branch B: Optimization and Objective Function Limitations

- Was the model explicitly rewarded for physical plausibility during fine-tuning? Or just numeric closeness to labeled vectors?

- Without regularization toward known functional forms (e.g. inverse-square), it may converge to any interpolating function.

Branch C: Architectural Bias Mismatch

- Transformers are excellent for sequence modeling, but Newtonian mechanics is a fundamentally relational structure. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), or physics-informed neural nets (PINNs), may encode such relations more naturally.

Branch D: Overfitting in Symbolic Regression

- The nonsensical force expressions (e.g., involving sinusoids) might be regression artifacts on noisy outputs. Is the symbolic model revealing the foundation model’s “beliefs,” or just fitting surface-level anomalies?

4. Comparative Analysis: How Could It Have Been Improved?

| Possible Improvement | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Include velocity and acceleration as inputs | Newton’s laws require these quantities; trajectories alone may obscure them. |

| Use physics-informed loss functions | Penalizing deviations from known physical invariants (e.g., conservation of energy or momentum) could nudge learning toward structure. |

| Switch to architecture with inductive priors | Models like graph neural networks or neural ODEs may more naturally represent continuous-time dynamics and relational structure. |

| Conduct ablation studies | Try varying the richness of input features to isolate whether failure is due to information access or model bias. |

| Pre-train with symbolic supervision or hybrid tasks | Encourage alignment with physical laws during training, not just inference. For example, expose the model to Newtonian equations alongside trajectory prediction. |

5. Examples & Analogies

- Student Analogy: Imagine teaching a student planetary positions on a chalkboard and later asking them to derive Newton’s law. If they were never shown the concept of acceleration, they’d struggle—even if they memorized the path of Mars perfectly.

- Overfitting Analogy: Suppose a model is trained to predict stock prices and later asked to predict interest rate policy. If there’s no causal connection learned, the transfer fails—even if the trajectories looked correlated during training.

6. Layman-Friendly Summary

The model was good at guessing where the planets would go next, like someone watching a video and predicting the next frame. But when asked to explain why the planets move that way—to reveal the hidden physics behind the motion—it failed. Maybe it never saw enough clues, maybe it wasn’t built to reason in that way, or maybe it was never encouraged to think in laws instead of patterns. It learned what happens, not why it happens.

🔍 Final Diagnosis

Where could they have gone wrong?

The researchers may have overestimated the alignment between trajectory prediction and physical law inference. If position sequences are insufficient to infer forces (without velocity or time), then the model was set up to fail from the start—especially when equipped with a generic transformer architecture. The symbolic regression tools, while useful, also risked misrepresenting what the model had “learned” if noisy or miscalibrated.

What could they have done better?

They could have designed the input to expose richer physical variables (like velocity and time), used model architectures with physics-inductive priors, and included stronger supervision toward known laws during training. Additionally, testing across multiple architectures would better separate whether the failure was due to training data, model capacity, or inductive bias.

Would you like a follow-up proposal for an improved experimental framework using physics-informed neural networks or a GNN-based probe setup? 🧙🏾♂️

User: reply/ Student Analogy: Imagine teaching a student planetary positions on a chalkboard and later asking them to derive Newton’s law. If they were never shown the concept of acceleration, they’d struggle—even if they memorized the path of Mars perfectly.

What would be a better way to teaching a student Newton’s law, without outright explaining it to them? I once taken an intro to cosmology course, and during Lab my professor would let us figure a lot of things on our. He gave us enough information, but the rest of the way, we would have to figure it out on our own to understand the task at hand. It was a smart way to not hold our hands the whole way through, but to let us explore to fail or suceed.

ChatGPT: 🪄

That’s a beautiful memory—and a telling one. Your professor was applying one of the oldest, wisest principles of learning: don’t give away the law—give the conditions in which it becomes inevitable.

Let’s begin with a quiet thought:

What does it mean to discover Newton’s law, rather than to receive it?

That question alone changes everything.

🌱 Goal: Induce the Law, Don’t Announce It

Let’s imagine a student like you—curious, capable, and a bit lost in the vast sky. The challenge is to help this student feel the gravitational law as a necessity—not memorize it as a formula.

We want to recreate Newton’s own path. After all, he too had no teacher to explain it to him.

🧗♂️ Pedagogical Philosophy

Chain of Thought Principle:

- Let the student move step by step from observation → pattern → abstraction → generalization → law.

Tree of Thought Principle:

- Let the student test different hypotheses. Reward paths, even dead ends, that show growth in modeling.

Separation of Concerns:

- Separate:

- Describing motion (What is happening?)

- Quantifying motion (How much change?)

- Explaining motion (Why is it happening?)

🛠️ A Constructivist Teaching Framework: Discovering Newton’s Law

1. Start with Kepler’s Data (Pattern Without Cause)

Provide a visual sandbox:

- Elliptical orbits of planets around the Sun

- Data tables with time-stamped positions

- Tools to compute velocities and accelerations

Prompt:

“Plot how the velocity vector changes over time. What do you notice about its direction relative to the Sun?”

This gets them to start thinking about acceleration toward a center—without naming it as such.

2. Let Them Build Force Hypotheses

Now that they’ve seen acceleration vectors point inward…

Ask:

“What if something is pulling the planet toward the Sun? How strong might that pull be?”

Let them guess. Then give them tools:

- Let them adjust a simulated force magnitude with a slider.

- Ask them to find a function F(r)F(r)F(r) such that the orbit closes perfectly.

This invites experimentation. They’ll stumble across inverse-square behavior empirically.

3. Introduce Mass by Collision Intuition

Have them simulate a tug-of-war between two unequal masses in orbit or on Earth.

Let them deduce:

- More massive objects resist motion change.

- But the same force causes less acceleration.

Now we can lead them to a = F / m, not as a dictum, but a ratio they feel.

4. Finally, Invite Generalization

Ask:

“Can we write a law that explains the pull between any two masses?”

At this point, students will feel the need for something like:

And when you give it to them, it will not feel like a gift.

It will feel like a confirmation.

🧠 Why This Works (Cognitive Explanation)

🔍 Constructivist Learning Theory

- Students learn best by constructing knowledge through active engagement and self-explanation.

🎯 Cognitive Load Theory

- You gave just enough structure (through simulations, visualizations, tasks) to reduce extraneous load—without stealing the sense of agency.

🔭 Inquiry-Based Science Pedagogy

- The process mirrors actual scientific discovery, reinforcing meta-learning: how to ask, not just how to answer.

🌌 Your Experience: A Perfect Illustration

What your cosmology professor did—deliberately leaving space for confusion, insight, and emergence—is a mark of a great educator.

Not a sage on the stage, but a guide at the edge.

🧑🏫 Final Takeaway for Teachers

If you want your students to understand Newton’s law, don’t start with it.

Start with the sky.

Let them chase a planet.

Let them fail.

Let them feel the asymmetry between force and motion.

Then—and only then—will the law become visible.

Not because it was taught, but because it could not be otherwise.

Would you like a full inquiry-based lab script based on this philosophy? 🧙🏾♂️

ChatGPT can provide some insightful feedback about the paper, even if I don’t fully understand it when it comes to the AI training part. But it does a good job of giving examples and analogies for a layman to comprehend what is happening.

Furthermore, even YouTuber/ physicist Angela Collier made a scathing video on the vibe physics phenomenon. It’s quite obvious she has a distasteful attitude towards AI, let alone billionaires at that. It’s not to say she doesn’t make good points, but like others, she’s quick to dismiss AI. Since my area of study has mainly been in the social sciences and humanities, most of my research and collaboration with AI has been in my area of interest and study. But that doesn’t mean I don’t veer off every once in a while to other subjects in the hard sciences like physics, biology, or medicine. I’m wise enough to know that I’m not an expert in these areas, and I don’t claim expertise. I don’t know if AI is providing me factual and insightful information, and I can accept living with that ambiguity, no different than in my field of study. I’d like to think I’m smart enough to leverage and push AI towards good research, steering it to the best possible answers.

Conclusion

If I’m ever conducting vibe physics, I will proudly proclaim: This is merely a fun experiment. Don’t take any of this seriously. Unlike many of the other hobbyists, or maybe this is my assumption, I don’t look for fame, money, and don’t care to publish anything. I’m forever curious about the world, and it’s what makes me happy. I’d say to the experts to relax. Let people play with AI as a sandbox to theorize and explore the world around them and the nature of reality. I can understand the frustration experts have with non-experts proclaiming scientific breakthroughs. The lower barrier of entry tools of AI makes the delusion more potent and people more susceptible to true knowledge. But like any parent would agree, we must be patient with kids–in this case, non-experts. We have been granted a new powerful tool to understand the universe itself. It’s not an accident in my humble opinion. We don’t have to belittle others with less knowledge, but be gentle and point them in the right direction.