The Meta-Peer Review Process.

Intro

The Intellectual Dark Web’s poster child and dark lord, Eric Weinstein, is someone whom I follow on X.com. Last week, I watched a recently uploaded video discussion he had with Curt Jaimungal. Jaimungal has a YouTube channel that focuses on the Theory of Everything by inviting various guests, mostly from the scientific community who study Physics, Philosophy, and the nature of reality. Weinstein was invited to discuss his theory of everything: Geometric Unity.

The discussion that took place covered mostly advanced physics or mathematics, an area that is not within my area of competence. As a layman, most of their discussion went right over my head, and it was as if aliens were speaking another language I couldn’t comprehend, despite being someone who contemplates the nature of reality mostly from a philosophical, spiritual, and mystical level. I promised one day that I would go over Geometric Unity with AI by going through his papers (if possible to get my hands on), lectures, and videos to understand it (even by a sliver) to see what it has to offer, and if it is truly a breakthrough in the scientific field. Weinstein seemed to appreciate that there stood someone across from him competent enough and intellectually open to discuss his theory. The audience may be split on what occurred, yet it was good to see an honest and open conversation on a dense topic.

Weinstein coined the term Intellectual Dark Web as a sort of an alternative to the narratives spewed by mainstream media. This group of intellectuals is like the punk rockers of the internet, including the likes of famous internet or podcast figures like Jordan Peterson and Joe Rogan. I don’t particularly like using the word pseudointellectuals as others throw around flimsily, and it would be off-putting and downright hateful to label folks using this derogatory term. I’m of the opinion that we have more than enough space for both science and anything labeled as pseudo. Despite the growing popularity of pseudoscience and folks finding it concerning, I think it’s counterproductive to quickly dismiss all their claims. In the end, the truth stands out as undeniably true, and pseudoscience is part of the process, and exercise, though cautionary, is best to find it.

I think people, perhaps stemming mostly from the scientific community, are usually more concerned with the rise in popularity of pseudoscience. Constant headlines are jabbing at Robert F. Kennedy Jr., especially in his new role in the Trump administration as the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Most headlines attack and undermine his beliefs on vaccines, autism, and other health-related issues. That’s fine and dandy. These articles can continue to speak their truth, and call him out when he’s wrong, but Kennedy perhaps has something to contribute as well, and is knowledgeable in something, and is willing to learn more as he continues his role.

The scientific community (i.e., the expert class) should also recognize how smart the audience or viewers can be. They may underestimate the power of good information disseminating as well as bad information. We can trust that people can weed out truth from fiction, although not always perfectly. There are certainly ways in which groupthink, bad thinking, or simply taking people’s word for it can creep up and can be a cause for concern within a pseudo-community who are wrestling with alternative claims to traditional science. I still believe that we can benefit from alternatives and creative thinking to the staleness and dullness of institutionalized science.

Eric Weinstein, despite going to Harvard and earning a PhD, has had a love/hate relationship with the traditional path of science and all its glory. This was due to the fact that he endured some bad experiences in the scientific community early on, where his theory or contributions were largely ignored. When someone else had shared a similar contribution, it was later acknowledged. If I were in his shoes, I would completely understand and be upset as well. Anyone would be infuriated if their work was actually something noteworthy, was largely met with dismissal, and yet, some years later, another scientist pulls on the same thread as you did, and because of their prestige, they are seen as more credible, and thus, the same or similar work is met with glorification. You can see how that could be seen as quite odd, and unjust, where one side is met with skepticism or perhaps even hostility while the other is met with invitation and praise, despite the only difference being perhaps the character of the person behind it and their reputation. Name and recognition make all the difference, regardless of the claims saying otherwise. Name and recognition can cloud our judgment of a scientific work when we should look past the name and focus solely on the work.

Putting our faith in name and recognition is bad for science. If we go back in history, Albert Einstein was met with the same skepticism and dismissal by the scientific community. Early in Einstein’s career, he didn’t have the social capital with elite scientists and institutions, nor the reputation of being a brilliant scientist (perhaps only in his small circle). Yet, he went on to change the entire scientific paradigm. It makes you wonder how many brilliant people faced the same situation? How many Einsteins were dismissed and largely discredited, misunderstood, and misrepresented?

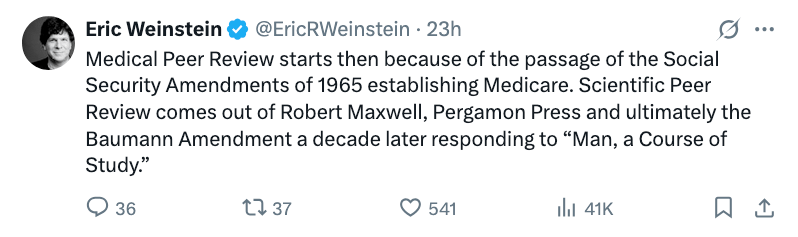

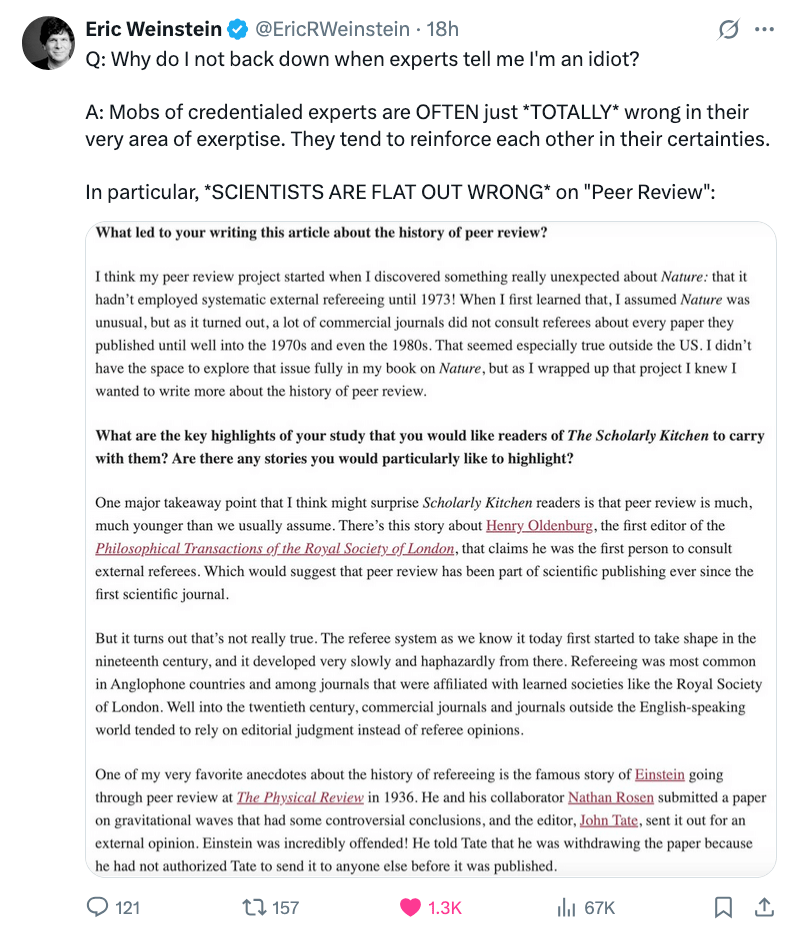

With all that said, it comes as no surprise that Eric Winstein would have disillusionment, resentment, and contempt for the scientific establishment, and with the word “peer review.” He has constantly bashed the term peer review in the past, so it’s nothing new. I was not privy to hard-lining questioning peer review before as much, but I at least somewhat questioned it when learning a bit about the history of science, the philosophy of science, or weird tricks people use when publishing their work, like p-hacking. Or even the sociology of science and how certain things get funded, such as how certain industries, like a tobacco or an oil company, can manipulate scientific research to mislead the public when it serves their agenda.

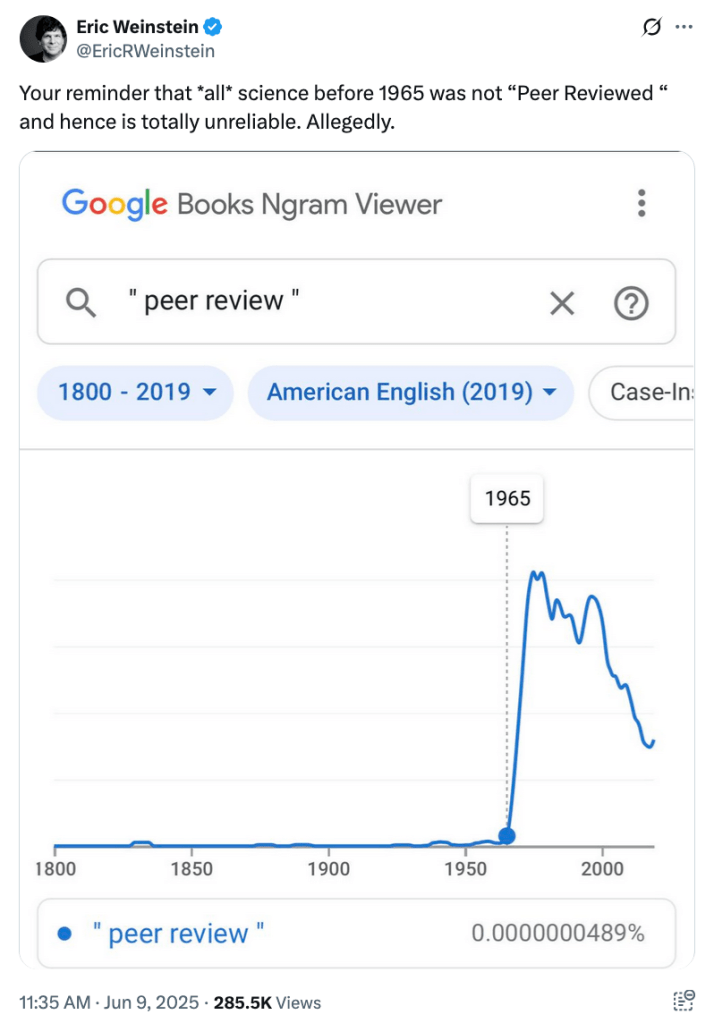

Weinstein’s recent X post:

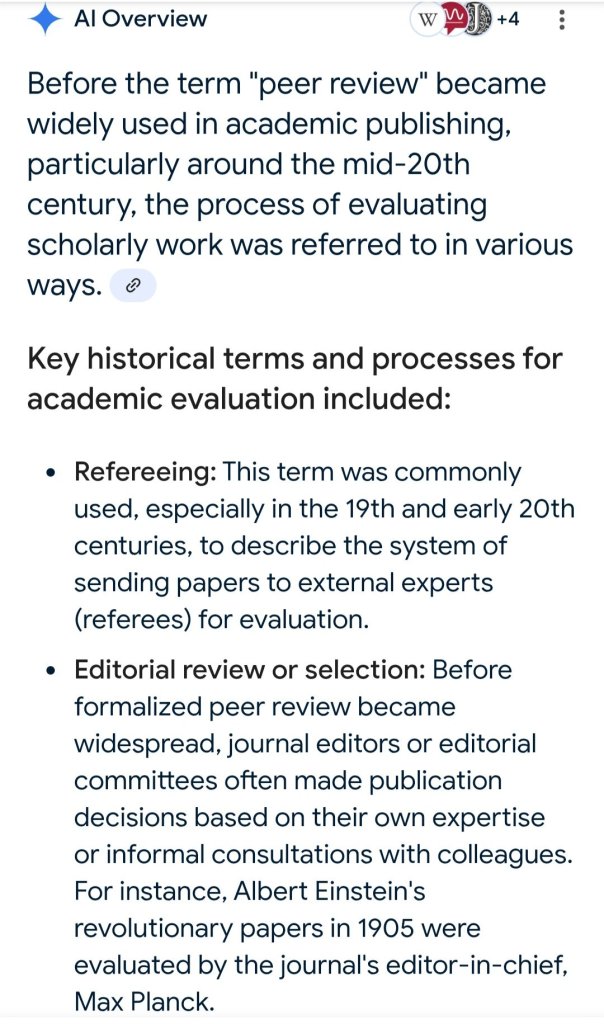

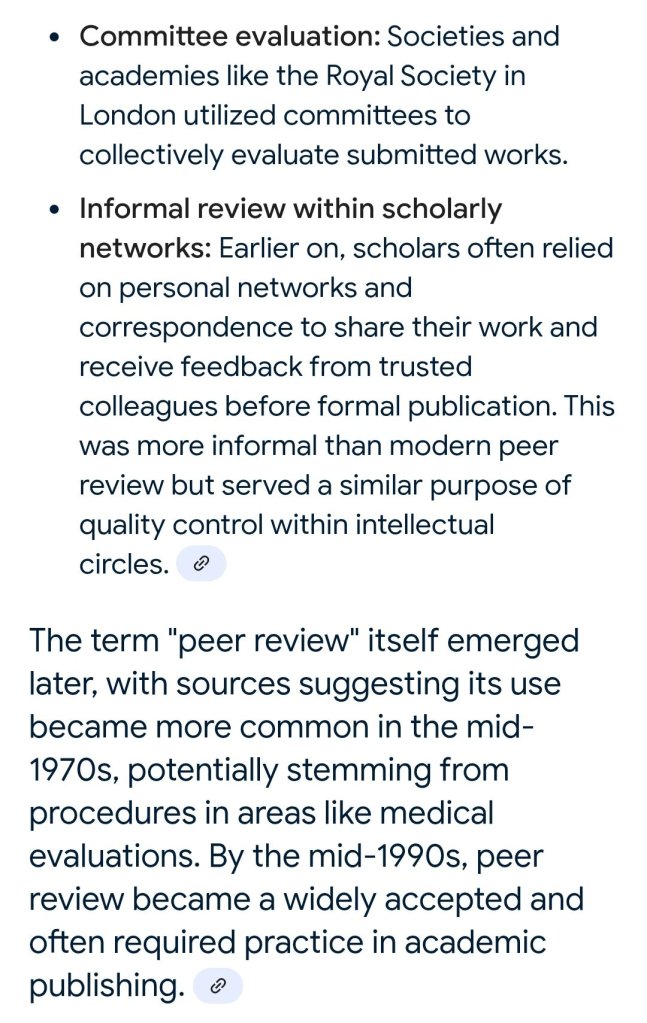

It’s not the first time Weinstein posted something like this, and not the first time I checked on Ngram myself. But my instinct was to again follow up on this post by doing some digging myself. I was critical of his post because it seems somewhat misleading, but I wanted to dig further with an honest, quick research. My initial instinct is that the concept of “peer review” may not have been known or formalized pre-1965. It doesn’t discount that some version of it was practiced, even if it was messy, disorganized, or went by a different term. I asked ChatGPT, and it surprisingly took its sweet time to answer. (Later found out via Reddit that this delay in response was probably because the website was experiencing issues this morning.) Nonetheless, I uploaded the screenshot of the post to ChatGPT and asked it:

User: Provide your honest thoughts on this post.

ChatGPT:

🪄

This post by Eric Weinstein is provocative, a bit cheeky, and layered with critique—both about scientific authority and how we retroactively judge knowledge. Let’s unpack it slowly.

First: What is the claim?

Eric is pointing to a Google Ngram graph showing that the phrase “peer review” only spikes in usage after around 1965. He then sarcastically reminds us that this would imply all pre-1965 science is “totally unreliable”—a jab at those who uncritically fetishize peer review as the only legitimate gatekeeper of scientific knowledge.

So he’s not exactly saying peer review is bad—he’s mocking the overreliance on it as a retrospective purity test.

Next: Does the Ngram graph mean peer review didn’t exist before 1965?

Not quite.

The term “peer review” may not have been widely used in books prior to 1965, but peer review as a practice predates that. Some form of it has existed in various ways for centuries.

- The Royal Society of London, for example, used a form of manuscript review in the 18th century.

- The journal Medical Essays and Observations (1731) reportedly had an editorial review process.

But standardized external anonymous peer review—the modern version we now recognize—only became institutionalized across most journals post-WWII, especially in the Cold War era. By the 1960s and ’70s, it became the norm, not the exception.

So the graph isn’t showing the absence of peer review, but rather the rise of formalized language and discourse around it.

The deeper critique:

Weinstein’s post is really about epistemology. He’s pushing us to ask:

Should we dismiss all science done before peer review became institutionalized?

That would mean tossing out Newton, Darwin, Einstein, Curie, and most of 20th-century physics—including quantum mechanics and relativity. Obviously, that’s absurd.

So his rhetorical point is: “Just because something wasn’t peer reviewed doesn’t mean it wasn’t good science.” Conversely, just because something is peer reviewed doesn’t mean it’s true or reliable.

And that’s a fair caution. Peer review is a filter, not a guarantee. It can help prevent error—but it also reflects biases, power structures, and groupthink.

What he doesn’t say (but maybe should):

There’s a difference between:

- Scientific knowledge production

and - Scientific institutionalization and dissemination.

Peer review became necessary as science scaled—to help journals manage submissions, establish credibility, and screen for fraud. But many breakthroughs were produced outside of such systems—often by independent thinkers or in less formal environments.

The irony is: the more bureaucratized science becomes, the harder it can be for radical ideas to enter. That’s one of Weinstein’s long-standing concerns—he believes science has become self-reinforcing and exclusionary, punishing intellectual dissent.

Whether you agree with him or not, his critique lands especially well if you’ve felt that the institutional machinery of science doesn’t always serve truth—sometimes it serves itself.

One final note on the graph:

Google Ngram tracks phrases in books, not peer review practice itself. So while it gives us a rough linguistic and cultural signal, it’s not definitive evidence of when peer review began. It reflects visibility, not necessarily existence.

Final Answer:

Eric Weinstein’s post uses irony to critique the modern fetishization of peer review, highlighting that much of the foundational work in science occurred long before the term became common. While the Ngram graph doesn’t prove peer review didn’t exist pre-1965, it does reveal when the concept became culturally central. His deeper point—questioning the idea that institutional peer review is the sole guarantor of scientific reliability—is philosophically sound, even if rhetorically sharp. The real question he invites us to consider is: How do we balance tradition, authority, and innovation in the pursuit of truth?

🧙🏾♂️

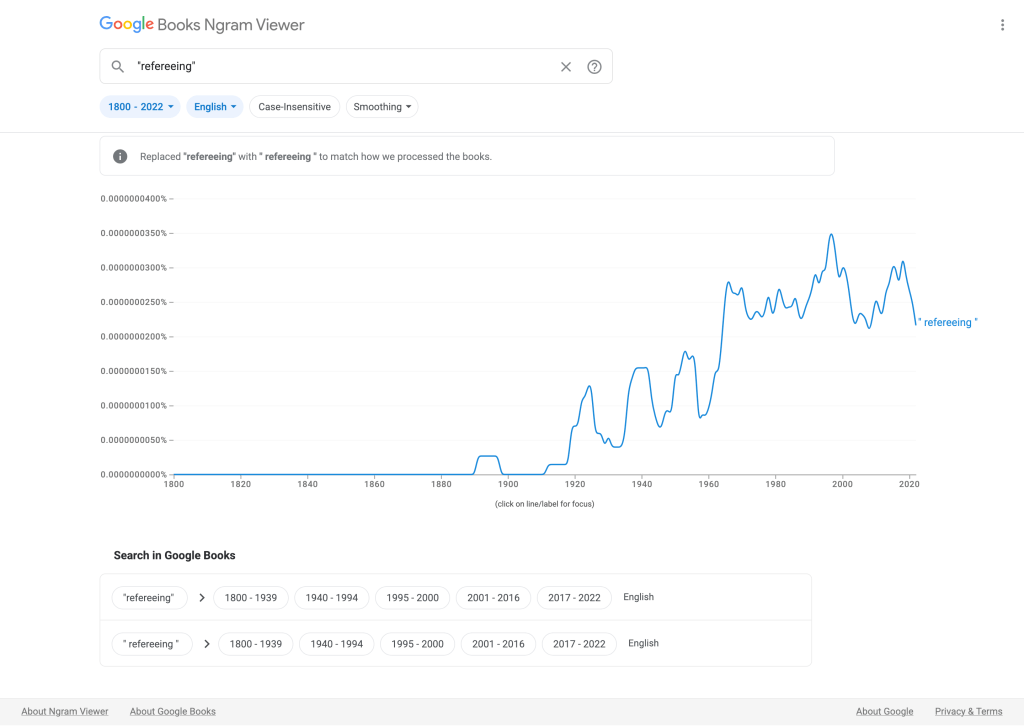

User: What word(s) were used before “peer review”? I tried several on Ngram, but the only one was refereeing.

ChatGPT: Ah, yes—this is a subtle and fascinating question. You’re essentially asking:

What language did the scientific community use to describe the evaluation of ideas before “peer review” became a formalized phrase?

Let’s take it slowly, and think aloud.

🧠 First principles: What was peer review before it was called “peer review”?

Before the bureaucratic phrase crystallized, the social function of peer review—scrutiny, validation, endorsement—still existed. But it was described differently. Some terms that served similar rhetorical or institutional functions include:

📜 Possible Pre-1965 Terms or Phrases

Let’s explore candidates—none identical in meaning, but several related:

1. Refereeing

You found this, and yes—it’s the most direct predecessor.

- Used especially in British and European academic journals.

- A “referee report” was what we now call a peer review.

- Still in use today, especially in mathematics and economics journals.

2. Editorial Review

- Editors (often prominent scientists) would evaluate papers themselves or ask colleagues informally.

- So this term was more common in earlier scientific publishing.

- This was less about peer equality and more about editorial gatekeeping.

3. Assessment / Evaluation

- Used more broadly across government and scientific societies.

- You’ll see phrases like “the work was evaluated by a committee of experts.”

4. Examination / Scrutiny

- Older, more general terms. They appear in scientific proceedings, especially 19th-century ones.

- E.g., “subjected to scrutiny by the society” or “examined by Dr. So-and-So.”

5. Judgment of colleagues or criticism by fellow scientists

- These weren’t technical terms, but they point to the informal sociological structure of validation—think Royal Society meetings, letters, or salons.

6. Vetting

- Occasionally appears, especially in administrative or military science contexts.

- “The proposal was vetted before publication.”

7. Reports / Recommendations

- Committees or panels would issue “reports” on submissions—common in funding agencies or institutional science.

🧪 In Practice: How Did Science Work Before Formal Peer Review?

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many journals were controlled by:

- A small number of editors (often elite scientists),

- Scientific societies (e.g., Royal Society, National Academy),

- Or even governments or philanthropies (e.g., Carnegie, Rockefeller).

The review was often:

- Personal (a letter or in-person comment),

- Hierarchical (a prominent figure decides),

- Slow and informal, not codified.

There was review—but not anonymity, formality, or standardization.

🧬 Example phrases from old literature:

If you search through pre-1950 journals or books, you’ll find things like:

- “Communicated by Professor X” (a form of endorsement).

- “With the approbation of the society…”

- “This communication was deemed worthy of publication…”

- “On recommendation by the examining committee…”

These phrases indicate some review was taking place—but it wasn’t called “peer review” and didn’t follow today’s structure.

🤔 Why didn’t “peer review” become popular until the 1960s?

That’s worth pausing on.

Possible factors:

- Cold War science boom → need for accountability and trust.

- Explosion of academic publishing → need to manage volume.

- Institutionalization of funding (NSF, NIH, etc.) → standard rules.

- Rising concerns about fraud or pseudoscience → formal safeguards.

“Peer review” became a standardized term because it was a standardized process—a response to the scale and complexity of postwar science.

🪞 Final Reflection:

Language like “refereeing,” “editorial judgment,” and “evaluation by experts” served the same social function as “peer review” before the term existed. What changed wasn’t just the phrase—but the professionalization and bureaucratization of scientific gatekeeping.

So, if you want to study this linguistically, I’d suggest using:

- “Refereeing”

- “Editorial judgment”

- “Committee evaluation”

- “Communicated by”

- “Examined by the society”

…in the Ngram viewer, and also dig into journal archives (e.g., Nature, Philosophical Transactions, PNAS pre-1950).

Final Answer:

Before the term “peer review” became common, the practice was described using words like refereeing, editorial judgment, evaluation, or simply review. Older literature often used phrases like “communicated by,” “examined by the committee,” or “recommended for publication” to signal scrutiny. The concept existed, but the formal phrase—and the bureaucratic process it represents—only crystallized post-1960s. 🧙🏾♂️

Next, I googled: What was used formally as a word before peer review? I think I had another variation of a similar search previously. Still, same core finding.

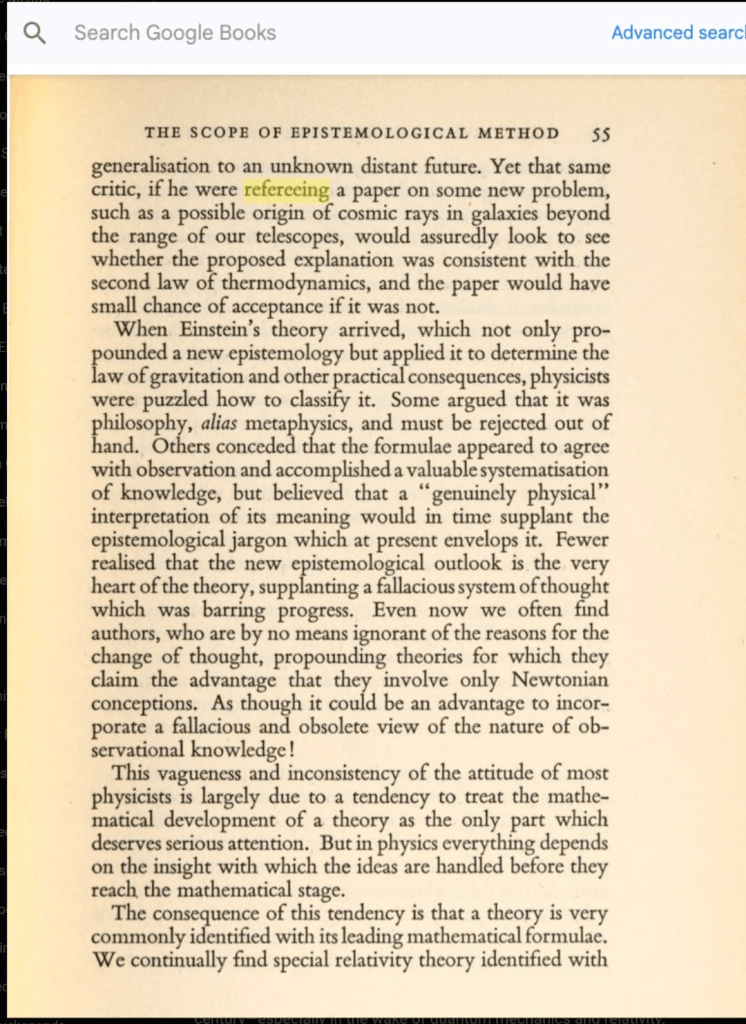

I then went on Google Ngrams to try searching for different words that have a semblance to peer review and may have been used back then, as far back as the 1800s. Since I can’t remember all the words I’ve used, I did use the ones provided by Google, such as editorial review and selection, to no avail. On Google Ngrams, you can click on the year down below, and I selected one between whatever date, which lands you on the Google Books page. I tried “refereeing” and failed to find anything relevant since it was mostly related to sports. I thought to put the word “science” next to refereeing and found one particular book that stood out related to science. Alas something!

Random thought: Is Google Ngrams a good metric? Is Google Books a good metric? Do they have every book ever published from the 1800s on? What about books that weren’t published or published before then? What about articles, pamphlets, letters, etc., that may show evidence of something akin to the peer review process? What of oral history? What about history that wasn’t written or passed down, let alone survived?

The book was “The Philosophy of Physical Science, Tarner Lectures 1938,” by Sir Arthur Ellington (1939). Oddly enough, despite the old age of this book (meaning expired copyright claims, it was not available in its entirety. I was able to get a glimpse of some of its pages. Here’s the initial page I clicked on for further inspection, where the word “refereeing” appeared once:

I took more screenshots of the few pages before and after (the start of the chapter) to upload to ChatGPT for further inquiry (Note: pages 51-52 were not shown in this preview). I did not tell ChatGPT the title of the book. This is a subtle but important point because it was able to pick up rather quickly, probably because it was trained on the vast data. I was impressed that it was able to figure out the title without searching the web.

User: Explain, summarize, and break down this screenshot I took of a book.

ChatGPT: 🪄

Let’s take this step by step. The screenshots you’ve shared are from Sir Arthur Eddington’s work, most likely his 1939 book The Philosophy of Physical Science. This text represents one of the most important philosophical interpretations of physics from the early 20th century—especially in the wake of quantum mechanics and relativity.

We are in a section titled “The Scope of Epistemological Method”, which spans multiple pages. Eddington is trying to uncover how epistemology—the theory of knowledge—relates to modern physical science.

I’ll proceed by interpreting the content thematically, with some close reading and philosophical reflection, beginning with your core question: what is Eddington trying to say?

📘 Thematic Summary

1. Physics as Epistemology, not Just Ontology

Eddington begins by shifting the lens of physics from describing external reality (ontology) to analyzing knowledge itself (epistemology). This is radical for his time.

- He argues that modern physics, particularly relativity and quantum mechanics, are not merely describing things in the world—they are describing the structure of our knowledge about the world.

- He contrasts this with classical physics, which assumes it is describing the external world directly.

“The characteristic of epistemological physics is that it directly investigates knowledge, whereas classical physics… endeavoured to investigate an entity (the external world)…”

This is the first major conceptual move. Eddington is saying: Physics has changed from being a mirror of nature to a mirror of how we know nature.

2. The Role of Symbols and Probability

He highlights the symbolic nature of modern physical language—especially in quantum theory:

- Equations don’t describe “things” directly; they describe relationships between observables.

- These observables are elements of knowledge, not entities.

- Thus, modern mathematical physics has become a kind of epistemological mapping, tracking what we can know and how we can express uncertainty.

“The mathematical symbolism describes our knowledge, and the mathematical equations trace the change of this knowledge with time.”

Probability, then, isn’t just about randomness—it’s about how inexact or partial our knowledge is. It has moved from a statement about physical systems to a statement about our information about them.

3. Critique of Scientific Dogma

Eddington criticizes the conservative mindset of many physicists who still cling to outdated Newtonian or classical frameworks:

- He notes that even when scientists accept new theories like relativity or quantum mechanics, they often do not fully absorb the epistemological implications.

- They accept the math, but not the underlying shift in worldview.

“There is an unaccountable reluctance to develop scientific epistemology systematically.”

He suggests that physicists have grudgingly accepted the new paradigm but have not yet integrated it into the routine of scientific advance.

4. Refereeing and Scientific Judgment

You pointed out the word “refereeing”—a precursor to the now-ubiquitous term peer review. In Eddington’s usage:

- The “referee” evaluates whether a paper’s theory complies with known scientific laws (e.g., the second law of thermodynamics).

- This suggests a gatekeeping function long before formal peer review as we know it.

But there’s a deeper implication here: evaluation is itself epistemological. What counts as plausible depends on how one conceives knowledge.

So refereeing isn’t just about quality control—it’s a form of epistemic policing.

5. Einstein’s Revolution and the Limits of Interpretation

He discusses how Einstein’s theory disrupted existing epistemological categories:

- Some physicists couldn’t decide whether relativity was philosophy or science.

- Others realized that Einstein had introduced a new epistemology, which was more scientific than the older frameworks.

Yet even as this revolution occurred, many continued to work within obsolete conceptual structures.

“Even now we often find authors… propounding theories… involving only Newtonian conceptions.”

He’s critiquing the inertia of old ways of thinking. In his view, science’s progress is hampered not by data or theory, but by philosophical blind spots.

6. Science Needs Philosophy

Perhaps Eddington’s most provocative point is that science cannot proceed without philosophy—especially epistemology.

- Without a coherent philosophy of science, we are left with a patchwork of methods, theories, and assumptions.

- Scientists may resist this claim, thinking philosophy is “metaphysics” and therefore unscientific.

But he insists that science is already full of metaphysical assumptions—especially about what constitutes observation, knowledge, or valid inference.

“What really concerns our inquiry is that the leaders of physics have so far committed themselves in accepting its aid that its complete assimilation is only a question of time.”

In other words: they’re already using epistemology, even if they don’t know it yet.

🧩 What’s the Overall Argument?

If I were to reduce this to a single thread:

Eddington is arguing that modern physics has—willingly or not—become a branch of epistemology. The shift from Newtonian to Einsteinian and quantum theories requires us to rethink not only what the universe is, but what it means to know anything about it. Yet many scientists have accepted the results of this shift without accepting the methods or worldview that made them possible. Until epistemology becomes central to scientific practice—not just its emergency backup—we will continue to repeat old errors.

📘 Final Answer:

Arthur Eddington, in The Philosophy of Physical Science, argues that modern physics must be understood not just as a description of the external world, but as a theory of knowledge itself. He critiques physicists for accepting revolutionary theories like relativity and quantum mechanics without assimilating the epistemological implications. Using terms like “refereeing,” he hints at early forms of what we now call peer review, but his deeper concern is that science still resists systematic philosophical inquiry—especially into its own foundations. He believes this resistance limits scientific progress. His call is for a science that fully embraces epistemology as method, not just as theory.

🧙🏾♂️

I eventually did find a downloadable version of the book after much searching (not easy to find).

I looked at more of Eric Weinstein’s tweets following the initial post, and the comment section.

Someone in the comment section used Grok for answers and shared it.

I was not aware that words like refereeing and others were used before peer review was formalized and popularized. The history of peer review is not something I have thought about or researched before in depth. It’s good to question the history of the terminologies we use to get a better grasp and picture of the whole story.

Whether or not Eric Weinstein’s critique of peer review and how science is conducted today is up for debate. His critique is somewhat justified, and I can understand where he’s coming from, provided the context of his experiences. He may be wrongly painting the entire structure with a broad brush and accusing it as a corrupt system. I’m no expert in this area of peer review process and publishing, so I can’t say for sure. Some articles go more in depth on this system, especially critiquing the capitalization or financialization of publishing academic articles, and how that area became corrupted.

Additional Sources:

https://mitcommlab.mit.edu/broad/commkit/peer-review-a-historical-perspective/

https://ethos.lps.library.cmu.edu/article/id/19/

The article Eric Wienstein shared via x: Article link.

Bonus:

// Since the 1938 Eddington book didn’t want to upload on ChatGPT, I decided to create a new chat to get a quick history of peer review. Here’s a question worth contemplating: What is the meta-peer review process?

User: You mentioned proto-peer review. What would meta-peer review entail?

ChatGPT: ChatGPT said:

🪄

That’s a beautifully subtle question.

“Meta-peer review” sounds almost paradoxical—a review of the review process itself. If peer review evaluates content, meta-peer review evaluates the evaluators, the criteria, the system. It steps back. It asks:

“How do we know that this judgment of validity was valid?”

Let’s think aloud, gradually, through what this could mean—first conceptually, then practically, and finally, philosophically.

🧠 I. Conceptually: What is meta-peer review?

Let’s define it carefully.

- Peer review: A process where a scholar’s work is evaluated by others considered their intellectual peers—ideally for rigor, originality, and relevance.

- Meta-peer review: A second-order process that evaluates the peer review process itself. That might mean:

- Assessing the quality of individual reviews

- Evaluating reviewer biases

- Comparing reviewer consistency

- Auditing editorial decisions

- Reflecting on the norms and epistemic assumptions of peer review

So, while peer review scrutinizes content, meta-peer review scrutinizes the architecture of scrutiny.

🔧 II. Practically: How does meta-peer review occur?

Some real-world examples and analogs:

✅ 1. Reviewer rating systems

- Platforms like Publons or Peerage of Science allow rating of reviewers by editors or authors.

- This is a weak form of meta-peer review: it doesn’t question the system, but assesses its agents.

✅ 2. Editorial audits

- Some journals conduct internal audits to see if reviewers are being fair, timely, or consistent.

- This can reveal systemic biases—e.g., favoritism toward prestigious institutions or gender disparities.

✅ 3. Empirical studies of peer review

- Scholars conduct meta-research on how peer review works.

- Studies have shown:

- Huge variability in reviewer recommendations.

- Low inter-reviewer agreement.

- Evidence of status bias, language bias, institutional gatekeeping.

This kind of research constitutes meta-peer review in practice, even if not always called that.

✅ 4. Public and open peer review

- When peer reviews are published alongside papers, the reviews themselves become open to criticism and commentary.

- This creates an implicit meta-peer layer: the public can assess whether the reviewers asked good questions, or missed something crucial.

📐 III. Philosophically: What does meta-peer review imply?

This is where things get rich.

🧩 1. Recursive legitimacy

If peer review confers legitimacy on a claim, what legitimates the peer review?

Meta-peer review acknowledges that legitimacy is not a one-step process. It is recursive. It depends on trust in the evaluators, the criteria, and the institutions behind them.

But if that trust erodes—through bias, corruption, or inconsistency—we need higher-order mechanisms of scrutiny.

🧩 2. Who peers at the peers?

Just as Socrates asked who watches the guardians, meta-peer review asks:

Who are the peers of the peers?

This is a political question, not just an epistemic one.

🧩 3. Epistemic humility and systems of critique

Meta-peer review enacts a form of epistemic humility. It says:

“Let us not assume our vetting process is neutral. Let us examine it.”

In that way, meta-peer review is itself a philosophical gesture—a willingness to interrogate the rules of validation, not just the results.

🧬 IV. Speculative Extensions: What could meta-peer review become?

Let’s imagine more radical forms:

- Algorithmic audit of reviewer behavior: Using AI to detect patterns of bias or inconsistency in thousands of reviews.

- Crowd meta-review: Letting broader communities rate the helpfulness or fairness of reviews, not just editors.

- Meta-editorial boards: Panels that review editorial decisions themselves, especially in controversial rejections.

- Reflexive review practices: Requiring reviewers to disclose their assumptions, epistemic frameworks, or positionality when reviewing.

These would move us toward a reflexive, transparent ecology of knowledge.

✅ Final Answer:

Meta-peer review is the critical examination of the peer review process itself—its agents, its assumptions, its biases, and its institutional forms. It can take the form of rating reviewers, auditing editorial decisions, or conducting empirical studies on review quality. Philosophically, it challenges us to consider how trust, legitimacy, and authority are recursively constructed in knowledge systems. Ultimately, meta-peer review invites a culture of reflection, transparency, and epistemic humility—guarding not just the content of knowledge, but the conditions under which we come to trust it.

🧙🏾♂️