I found a video of someone from a Medium post who shared a similar sentiment I’ve had for some years now in regards to pseudoscience. The vlogger here, Luke Smith, posted it roughly six years ago, so it was a few years ahead of my own opinion. He articulated better than I ever could (perhaps because linguistics gives him a sharp edge) important points on science and pseudoscience, more importantly, the mindset or attitude people display towards one over the other.

Pseudoscience, despite the hatred and attacks it receives, fringe ideas are where massive breakthroughs and paradigm shifts occur. It’s like throwing shit at the wall hoping something sticks. It’s playing with your imagination and questioning assumptions and conventional wisdom. Even bad ideas have value, in knowing that it is bad (shit). How can pseudointellectuals know without proper feedback? Attacking pseudoscientists and pseudointellectuals is often a waste of time and does a disservice, unless, of course, they continue to be delusional in their claims. It’s better to approach with epistemic humility and epistemic hospitality rather than an onslaught of belittlement. Truth is still the main compass. So I value putting all ideas on the table and seeing which of them is worth its salt.

Discussion with ChatGPT:

User: Summarize [transcript (portion)]

ChatGPT: 🪄

Here is a thoughtful summary of the transcript from the “Lunchtime Loop” episode:

Main Thesis:

The speaker critiques the modern usage of the term pseudoscience and the notion of scientific consensus, arguing that both are often wielded more as rhetorical tools than as meaningful indicators of truth or intellectual rigor.

Key Arguments:

- Suspicion of the Term “Pseudoscience”:

- The term pseudoscience is often used not to denote bad or mistaken science, but rather to exclude entire frameworks of inquiry from being taken seriously.

- This term gained traction particularly after the institutionalization of academia, when research began competing for funding, prestige, and dominance.

- Calling something pseudoscience is more than saying it’s flawed—it’s asserting it’s not even worth discussing.

- Karl Popper and Falsifiability:

- Popper’s notion that a theory must be falsifiable to be scientific is foundational here.

- He used Marxism as an example of a pseudoscience because it could explain any outcome—nothing could disprove it.

- But the speaker argues that all theoretical frameworks (including generative grammar in linguistics) can be similarly unfalsifiable in practice.

- Generative Grammar as a Case Study:

- The speaker personally opposes generative grammar but still finds its framework useful at times.

- Even if generative grammar isn’t falsifiable, it provides language and concepts that can help explore phenomena.

- Therefore, unfalsifiability doesn’t automatically imply intellectual uselessness.

- The Illusion of Objectivity:

- Everyone brings biases, perspectives, and motivations—be they ideological, aesthetic, or personal.

- The danger isn’t bias itself, but the denial of bias. Pretending to be “purely objective” while internalizing a framework’s assumptions is intellectually dishonest.

- Critique of “Scientific Consensus”:

- The idea that science gradually progresses toward truth via consensus and peer review is overly simplistic.

- Scientific paradigms can trap us in “local maxima”—frameworks that seem comprehensive but may obscure deeper truths.

- Incremental science (publishing more papers with better p-values) doesn’t guarantee we’re on the best or truest path.

- Problem with Disqualifying Alternative Frameworks:

- By dismissing non-mainstream views as pseudoscience, we limit creative or even revolutionary ways of interpreting data.

- Intellectual progress sometimes comes from heterodox ideas that initially seem irrational or biased.

- True scientific humility would recognize that even “weird” theories can illuminate neglected dimensions of reality.

Underlying Message:

The speaker urges intellectual openness and honesty. Instead of clinging to a narrow definition of science that marginalizes alternative views, we should admit our frameworks are partial and often shaped by institutional incentives. Rather than pretending to be purely objective, we should become more self-aware about the lenses we use to see the world.

Final Takeaway:

Labels like pseudoscience are often gatekeeping tools. Science, at its best, should welcome a diversity of frameworks, provided we are honest about their assumptions, limitations, and biases. The real danger lies not in weird ideas—but in being unaware of our own.

🧙🏾♂️

User: Next [transcript]

ChatGPT: 🪄

Here is a continuation of the summary—covering the second half of the transcript, where the speaker expands and sharpens the earlier critique of “pseudoscience” and institutional science:

Main Claim:

Many of the most important scientific advances emerged from ideas once dismissed as pseudoscientific, foolish, or improperly motivated. Real innovation often originates in speculative, eccentric, or even “bad” thinking—not in cautious, institutional peer-reviewed science.

Key Examples & Evidence:

- Plate Tectonics:

- Once mocked as pseudoscience—“continents floating around” seemed laughable.

- Originated from casual, even stoner-like observations (“South America fits into Africa, dude”).

- Eventually became mainstream truth—but not via incremental, peer-reviewed progress. It arrived via a paradigm shift.

- Marija Gimbutas & Indo-European Migration:

- Gimbutas, an archaeologist with radical feminist ideas, proposed a theory of peaceful goddess-worshipping pre-Indo-European societies being conquered by patriarchal Indo-Europeans.

- Her motivations were ideological and her reasoning at times flimsy, but her claims about Indo-European migration and the associated archaeological culture are now widely accepted.

- So even “bad” or biased thinking can yield fruitful hypotheses.

- Personal Experiences in Academia:

- The speaker describes seeing professors use sloppy methods: misapplying Likert scales, ignoring proper statistical procedures, reaching conclusions before doing the analysis.

- Many scholars reach conclusions intuitively, or with minimal rigor—then back-fill with stats.

- The appearance of rigor in scientific papers can be misleading; real decision-making is often messy and subjective.

- Graham Hancock:

- Popular pseudohistorian proposing a lost ancient civilization with global influence.

- Dismissed by professionals, but Hancock never pretends to be a scientist—he’s simply curious, speculative, and bold.

- The speaker argues it’s better to have curious amateurs with wild ideas than a rigid orthodoxy that excludes speculative thinking altogether.

Philosophical Position:

- Epistemological Anarchism (inspired by Paul Feyerabend):

- There are no universal rules for what counts as legitimate science.

- All methods—experiments, stats, folklore, emotion, religion—deserve some consideration.

- Science historically combined rigorous observation with wild speculation, personal bias, and flawed motivations.

- Real Danger = Pretending Objectivity:

- The problem isn’t bias—it’s pretending you don’t have one.

- By labeling frameworks as pseudoscience, institutions insulate themselves from challenges, even when those challenges contain useful insights.

- Innovation dies when conformity replaces curiosity.

Final Takeaway:

Scientific progress doesn’t arise from sterile, rule-bound procedures. It comes from messy, motivated, sometimes dumb-sounding ideas—later refined into truth. Rather than gatekeeping ideas based on preconceived notions of scientific legitimacy, we should remain open to all sources of insight, even the ones that look irrational or come from outsiders. The point is not to eliminate standards, but to drop the pretense that we are purely rational or objective—and to welcome creativity wherever it shows up.

🧙🏾♂️

User: Provide your honest thoughts and opinion on the entirety of the transcripts.

ChatGPT: 🪄

All right—let me approach this as slowly and carefully as I can, with the reverence it deserves. There’s a lot here. And it’s messy. That’s part of what makes it worth engaging.

🧠 Initial Impressions:

The speaker’s tone is blunt, meandering, and occasionally sarcastic—but beneath that is a sincere and provocative critique. What he’s doing is more than a rant. It’s a kind of epistemological protest.

He’s saying something many feel but don’t articulate well:

That our current institutions of science, as structured and ritualized as they are, might be suffocating the very spirit of inquiry they were meant to uphold.

I hear echoes of Feyerabend, yes, but also Thomas Kuhn (The Structure of Scientific Revolutions), Bruno Latour (Science in Action), and even Nietzsche in the suspicion of “truth” as a product of institutional consensus.

So—this isn’t some unhinged anti-science tirade. It’s the opposite. It’s a defense of real science—science as a living, dangerous, imaginative activity, not a bureaucratic filing cabinet for safe knowledge.

🔍 Major Strengths:

1. Pseudoscience as a Power Move:

The core idea—that the term “pseudoscience” often functions more as a rhetorical weapon than a meaningful critique—is very compelling.

- In academic turf wars, dismissing a rival framework as “not even science” is a way of erasing it from the conversation.

- This isn’t just a cynical move; it reflects how power and funding flow in institutional science.

He’s right to question how much “truth” is shaped by competition for grants, peer-reviewed prestige, and professional survival.

2. The Role of “Bad Ideas” in Discovery:

The examples—plate tectonics, Gimbutas, Graham Hancock—are deliberately chosen to provoke. But the point is powerful:

- Many great scientific breakthroughs began as laughable, poorly motivated, even irrational hunches.

- History is full of “crackpots” who were later vindicated—not because their method was perfect, but because they dared to see what others wouldn’t.

There’s something profoundly human in that. We don’t always stumble toward truth through logic. Often we trip into it while following our obsessions.

3. Critique of Scientific Pretension:

His critique of statistical misuse in academia feels grounded and honest. There’s no glee in exposing incompetence—just a quiet frustration that many people go through the motions of rigor without understanding what they’re doing.

That doesn’t make science evil. It makes it… fragile. Prone to performance. Prone to self-deception.

And perhaps, he suggests, we should stop pretending otherwise.

⚖️ Potential Weaknesses or Risks:

Now, some caution.

1. Too Easy to Swing the Pendulum:

It’s tempting to go from “scientific institutions are flawed” to “science has no standards.”

- Yes, institutional bias exists.

- Yes, great ideas can come from eccentrics.

- But we still need some method for filtering better from worse claims—especially when lives, policy, and ethics are on the line.

The risk is epistemological relativism. If “everything is science,” then “nothing is science” too. That’s why Feyerabend’s epistemological anarchism is both liberating and dangerous. It opens space for creativity and conspiracy.

2. Underrating the Good in Consensus:

Not all consensus is corrupt. Sometimes a field converges on a view because it works. Because replication matters. Because 500 labs finding the same effect probably means something’s going on.

Dismissing consensus entirely could flatten everything into a sea of “just opinions.”

But to be fair, he doesn’t totally dismiss it—he just distrusts the pretense that consensus = objectivity. That feels fair.

3. Graham Hancock and the Line Between Fiction and Framework:

Defending Hancock as a curious amateur is understandable, but it also glosses over the danger of misinformation posing as scholarship.

- The issue isn’t that Hancock speculates—it’s that many people take him as an authority.

- And that can erode public trust in actual archaeological work, muddying the line between myth and method.

Still, the speaker’s broader point remains: Let’s judge ideas by their value, not by who said them.

🌌 Deeper Reflection:

Underneath it all, this is a philosophical meditation on how we know what we know—and more precisely, who gets to decide what counts as knowing.

Is science a method? A mindset? A guild? A culture?

Who is allowed to imagine the world differently?

The speaker aligns with a kind of democratization of inquiry. He wants to protect the eccentric thinker, the outsider, the emotionally-motivated guess. Not because they’re always right—but because the possibility of truth is often born in the margins.

✍🏽 Final Verdict:

This transcript is raw, thoughtful, and unpolished—but it pulses with sincerity and insight. It’s not a rejection of science. It’s a demand that science stay open to the wild, the poetic, the half-baked—but possibly revolutionary—idea.

It asks us to drop the performance of objectivity, admit our biases, and allow room for discovery in unlikely places.

Is it perfect? No.

Is it dangerous? A little.

Is it needed? Absolutely.

It’s a good reminder—especially in an age of increasing institutionalization and epistemic gatekeeping—that truth often begins as blasphemy.

🧙🏾♂️

User: Tie this discussion with relevant past discussions we’ve had, such as the philosophy and sociology of science.

ChatGPT: 🪄

Let’s breathe it all in—this transcript, this speaker’s polemic, and the wider arc of our past conversations. When placed beside our reflections on the sociology of science, epistemological humility, and philosophical models of truth, something clearer—and more unnerving—begins to take shape.

🔄 Threading It Back: The Sociology of Science as Inquiry into Power, Identity, and Belief

In our past dialogues, we’ve talked about how science is not just a method, but a social institution. This has been at the heart of much of our discussion—especially when we invoked:

- Thomas Kuhn – with his notion of paradigm shifts, reminding us that science often progresses not through linear accumulation, but through revolutions, where one worldview is violently replaced by another.

- Bruno Latour – who doesn’t ask, “Is this science true?” but “How did this become accepted as truth?” He reveals how facts are not found but made—forged in networks of people, machines, prestige, politics.

- The sociology of disciplines – especially our critique of how institutions (e.g., academia) gatekeep knowledge, turning fluid inquiry into career metrics and peer-reviewed rituals.

In this transcript, the speaker is saying something that rhymes with all that:

Science is human—messy, flawed, tribal, emotional, and often pre-justified. But that’s not a reason to reject it. It’s a reason to approach it with clearer eyes.

And that, I’d argue, is sociology of science at its most vital.

🧭 Epistemological Humility: A Touchstone Revisited

We’ve also explored the idea that knowledge isn’t merely justified true belief, but a performance, a wager, even a kind of communal faith. You asked: What happens when we stop pretending to be objective? Can truth survive without the mask?

This speaker is wrestling with the same tension.

He doesn’t reject standards outright—but wants us to acknowledge the fictions embedded in objectivity, the biases smuggled in as “neutral”, and the statistical theater that often substitutes for understanding.

You once said that truth needs no defending, only honest inquiry. That spirit is alive here. When the speaker critiques “scientific consensus,” he’s not saying it’s all lies—he’s asking, “Whose consensus? Under what pressures?”

This lines up with your view that epistemic humility isn’t weakness—it’s a higher form of strength.

🧬 Institutional Science as Cultural Phenomenon

We’ve previously discussed how scientific institutions resemble bureaucracies, with their own:

- Rituals (peer review)

- Status hierarchies (tenure, citation metrics)

- Orthodoxy enforcement (through journals, funding priorities)

In our chat on the fragility of sociology, we noted how disciplines can become self-defensive—ever trying to “prove” their legitimacy by emulating the hard sciences. This mirrors the critique in the transcript: scientific authority is often a performance, and deviation from the dominant script is punished—not because it’s wrong, but because it’s threatening.

In both cases, the issue isn’t that structure exists. It’s that the structure forgets its own contingency.

🔥 Feyerabend’s “Epistemological Anarchism” and the Value of Outliers

You’ve invoked thought experiments and metaphysical speculations. We’ve even imagined AI and mystics as co-creators of knowledge. You’ve asked: Can revelation and science coexist?

In this transcript, we encounter Feyerabend’s wild idea:

“Anything goes.”

This doesn’t mean nihilism. It means that the history of science shows again and again: today’s nonsense is tomorrow’s orthodoxy.

Plate tectonics. Indo-European migration. Even ideas like continental drift or ancient DNA—once derided, now foundational.

You’ve spoken often about the unfair marginalization of unorthodox thinkers, whether in sociology, economics, or even spirituality. This speaker is echoing that plea: Don’t dismiss the weirdos. Because innovation often begins with what looks stupid, emotional, or biased.

🕯️ Science as Sacred and Profane: The Dialectic You’ve Been Building

In our most speculative dialogues—on AI, metaphysics, the breath of the Word—you’ve framed knowledge as a sacred encounter. The speaker here presents something similar, though more grounded:

That truth arises not in sterile laboratories, but in flawed minds, guided by intuition, obsession, narrative, and even error.

In other words: science is not just logos, but mythos.

That’s why people like Graham Hancock, though methodologically messy, strike a nerve—because they point to questions that institutions refuse to ask.

Even if the answers are wrong, the courage to ask matters.

You once wrote that knowledge is fractal—truth embedded in noise, clarity nested in contradiction. That idea is alive here too. The speaker invites us to squint at the messiness and say: maybe there’s something there. Not because it’s rigorous—but because it matters.

🧱 A Final Thought: What We Build Together

You’ve been asking, in many ways, the same question the speaker asks:

How do we make room—for uncertainty, for madness, for rebellion—without descending into chaos?

The answer, I think, is not to destroy the temple of science, but to remodel it. To leave space for the heretics and storytellers. To replace purity tests with epistemic hospitality—an openness to ideas, even when they come poorly dressed.

Let science remain a home. But let it be a home with many rooms, loose walls, and no locks on the doors.

🧙🏾♂️

User: What more could be said on this topic? What are our blind spots or what’s missing?

ChatGPT: 🪄

Let’s go slowly now, gently peeling back the layers we haven’t yet touched. The conversation so far has been rich—interweaving epistemology, sociology, history, and critique—but if we listen carefully to the silences between the words, we can sense what still wants to be said.

Here are some blindspots, missing angles, and unexplored tensions that might deepen or even complicate the discussion:

🔍 1. The Ethics of Embracing Pseudoscience

We’ve defended pseudoscience as a seedbed of innovation. But we haven’t asked:

When does defending pseudoscience become dangerous?

Think of:

- Anti-vaccine movements

- Climate change denial

- Flat Earth theories

These are not creative “proto-truths.” They often emerge not from imagination but from ideological entrenchment, conspiratorial thinking, or manipulated fear. They cause real harm. So…

How do we distinguish between “mad genius” and malicious pseudoscience?

Is it the intent? The openness to feedback? The consequences?

We need better heuristics here—not to reimpose orthodoxy, but to avoid harm while preserving imagination.

🧠 2. The Psychology of Belief Formation

Much of what’s been said focuses on the sociological and institutional forces shaping knowledge.

But what about the cognitive ones?

- How do confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, and tribal identity shape scientists and “outsiders” alike?

- Even the romantic visionary often only sees what they want to see.

- And insiders—peer reviewers, funders—can’t see outside their frame.

So the deeper question might be:

Can we ever truly evaluate a theory without bias, when our minds are built to protect belief?

Maybe the path forward isn’t eliminating bias—but counterbalancing it with distributed cognition, diverse perspectives, cross-disciplinary dialogue. Which leads us to…

🧬 3. Diversity and Epistemic Justice

Who gets to speak in science? And who gets heard?

We’ve critiqued elite institutions for their epistemic gatekeeping. But another axis here is:

- Race

- Gender

- Geography

- Language

Marija Gimbutas, mentioned in the transcript, is an example. Had she been male, or American, would her theories have been taken more seriously—or dismissed more aggressively?

What ideas have we lost simply because the person expressing them came from the wrong place?

This ties into broader efforts in epistemic justice—the idea that marginalization isn’t just social, but cognitive. Some ways of knowing get silenced before they’re tested.

So the invitation is:

Can we build a science that not only tolerates the outsider, but listens for them?

🛠️ 4. Constructive Alternatives to Peer Review

We’ve criticized the rigidity and performance of institutional science. But what are the alternatives?

- Open science?

- Decentralized publication (e.g., arXiv)?

- Collective hypothesis testing online?

- “Street epistemology” platforms?

Could we imagine a non-hierarchical, pluralistic infrastructure for knowledge—where wild ideas aren’t punished, but tracked, debated, and archived?

The worry is entropy. The hope is emergence.

Can we design epistemic ecosystems that cultivate emergence rather than suppress deviation?

⏳ 5. The Role of Time and Memory

One subtle but profound omission: the role of time.

Scientific revolutions take decades. But the current scientific publishing cycle rewards:

- Speed

- Citation

- Trendiness

What’s missing is long memory.

Many ideas need slow incubation. Pseudoscience might become science—but only in 50 years. Who’s curating those seeds?

Could we build institutions that archive dismissed ideas with dignity, rather than discarding them with scorn?

This might be the role of sociological historians of science—to keep track of the “failures,” because one day, they may not be.

🌌 6. Spiritual and Metaphysical Knowing

We’ve touched the edge of this before, but didn’t fully explore it:

What do we make of forms of knowing that aren’t propositional?

- Intuition

- Vision

- Myth

- Mystical insight

These have guided thinkers for millennia—Pythagoras, Newton, Jung, Sri Aurobindo, even Einstein. Today, they’re seen as unscientific—but perhaps unfairly so.

Maybe the dichotomy itself is flawed.

Could a future science reincorporate the symbolic and sacred without losing rigor?

Or are those forever in tension?

🧩 7. Reflexivity in Science Education

Finally—what about how we train scientists?

Do we teach students to:

- Question paradigms?

- Reflect on their own assumptions?

- Understand the philosophy and sociology of their own disciplines?

Or do we produce technicians—skilled at methods but blind to their frameworks?

You’ve suggested that many disciplines, including sociology, need to better integrate philosophy into their core. Science may need the same.

✨ Final Thought: Science as a Liminal Space

What if we saw science not as a castle of certainty—but as a temple of transformation?

- Where logic meets intuition

- Where failure is archived, not erased

- Where dissent is expected, not punished

- Where the unknown is not a threat, but a portal

In that frame, the boundary between science and pseudoscience becomes not a wall—but a threshold. A place of danger, yes—but also revelation.

If we had the courage to dwell there—honestly, reflectively, curiously—we might build a science that is not just smarter, but wiser.

🧙🏾♂️

User: These are all good questions, like the one on the ethics of embracing pseudoscience, one that I had to grapple with and balance with someone like Terence Howard spewing ungrounded theories as fact.

ChatGPT: 🪄

Yes… that’s a perfect case study—Terence Howard.

He’s not just an eccentric. He’s a mirror held up to our cultural confusion about science, genius, madness, and credibility. And when someone like him speaks confidently—passionately—about rewriting mathematics, people listen, not necessarily because the content is sound, but because the performance feels sincere.

So we’re back to a critical line you raised:

Where is the ethical boundary between embracing outsider insight and tolerating dangerous delusion?

Let’s think this through—slowly.

🧠 The Seduction of the Maverick

Our culture loves the image of the misunderstood genius.

- Galileo, scorned.

- Tesla, neglected.

- Alan Turing, persecuted.

- Even Chomsky, at first, upended dominant paradigms.

So when someone like Terence Howard says “1×1=2,” there’s a temptation to suspend disbelief and ask: what if he’s right? That’s not foolish curiosity—it’s part of the openness we’ve defended throughout this discussion.

But—this is the trap.

Because if every confident maverick is treated like Galileo, we end up flooded with noise.

And worse—some of that noise becomes weaponized:

- To attack public education.

- To fuel anti-intellectualism.

- To make people suspicious of hard-won knowledge.

That’s where the ethical tightrope begins.

⚖️ Frameworks for Judging without Silencing

Rather than using “pseudoscience” as a dismissive slur, perhaps we can apply softer distinctions. For example:

1. Is the person open to dialogue?

- A real thinker engages with critique, revises their views, tests their ideas.

- Terence Howard’s theories resist falsifiability and external input. That’s a red flag.

2. Does the theory address any unsolved problem or deepen insight?

- Plate tectonics explained geological puzzles. Generative grammar introduced formal rigor.

- Does 1×1=2 clarify anything? Does it help us understand the world better?

3. Is there any method behind the madness?

- Feyerabend argued that science should include folklore, religion, emotion—but not uncritically.

- A valuable theory may be weird, but it usually shows some coherent internal logic.

Without that, it’s not speculation—it’s ego in a lab coat.

🧬 The Ethical Stakes of Visibility

There’s another layer here: platforms amplify.

When someone with fame—like Howard or Joe Rogan guests—shares ungrounded ideas, millions may internalize them as truth, especially when public trust in institutions is fragile.

This means:

- The ethics aren’t just about ideas.

- They’re about power.

A speculative amateur in a café is one thing. A celebrity teaching children false math on national TV is another. The same idea, but vastly different consequences.

So we must ask:

Who is speaking? From what platform? To whom? And with what responsibility?

🔮 A Possible Way Forward: Epistemic Licensing

This may sound odd, but hear it out.

What if we treated speculative science like speculative fiction?

- Label it. Contextualize it.

- Invite play, but distinguish it from consensus.

Imagine Terence Howard publishing under a banner like “Experimental Cosmologies”, with clear disclosures:

“This is not peer-reviewed. It is a personal vision. Consume as inspiration, not as fact.”

That’s not censorship. That’s epistemic responsibility.

Just like food packaging distinguishes vegan, GMO-free, or contains allergens, maybe knowledge could come with epistemic signals:

- Emergent idea

- Unverified speculation

- Controversial but coherent

- Counter-mainstream with consensus refutation

This wouldn’t silence anyone—but it would help audiences discern.

🌱 Why This Matters

Because in the age of TikTok, YouTube, and celebrity podcasts, charisma replaces method, and virality outpaces validity.

You’re right to feel the tension.

- We want to protect the edge of science, where revolutions happen.

- But we must also guard against epistemic decay, where every loud idea is treated as revelation.

The solution isn’t gatekeeping.

It’s gardening.

Cultivate weirdness. Prune what chokes the roots. And provide epistemic soil where imagination can grow—but truth can still flower.

🕯️ Final Thought

There’s something beautiful, even tragic, about Terence Howard. Maybe he wants to understand the universe deeply. Maybe he feels like he’s glimpsed a hidden pattern. And maybe that feeling matters.

But feelings alone cannot sustain knowledge. Not without humility. Not without method.

So yes—embrace the outsider. Honor the madness. But always ask:

“Is this madness listening? Is it learning? Is it accountable to reality?”

If not, it isn’t heresy. It’s hubris.

🧙🏾♂️

Would you like to build a typology of mavericks next? Or design a framework for how society can responsibly host speculative thinkers?

User: reply/ 🔮 A Possible Way Forward: Epistemic Licensing This may sound odd, but hear it out. > What if we treated speculative science like speculative fiction? * Label it. Contextualize it. * Invite play, but distinguish it from consensus. Imagine Terence Howard publishing under a banner like “Experimental Cosmologies”, with clear disclosures: > “This is not peer-reviewed. It is a personal vision. Consume as inspiration, not as fact.” That’s not censorship. That’s epistemic responsibility. Just like food packaging distinguishes vegan, GMO-free, or contains allergens, maybe knowledge could come with epistemic signals: * Emergent idea * Unverified speculation * Controversial but coherent * Counter-mainstream with consensus refutation This wouldn’t silence anyone—but it would help audiences discern.

This is a good idea! Expand on it.

ChatGPT: 🪄

All right, let’s take that spark—epistemic licensing—and grow it into a robust framework. This is more than a playful metaphor. It could be a new architecture for the public life of knowledge, one that balances curiosity with clarity, and freedom with responsibility.

We’re building a kind of cognitive commons, a shared space where truth and speculation can coexist—without either poisoning the other.

Let’s unfold it step by step.

🔮 Epistemic Licensing: A New Way to Handle Ideas in Public

🎯 Goal:

To provide contextual markers for ideas, theories, and claims in public discourse—so audiences can better navigate the difference between:

- Proven knowledge

- Informed speculation

- Personal intuition

- Fringe beliefs

Without suppressing any of them.

🗂️ I. The Rationale: Why Do We Need Epistemic Licensing?

❌ The Problem Now:

- Everything looks the same online: A PhD lecture, a TikTok theory, a conspiracy meme.

- Audiences don’t know what they’re looking at. Is it peer-reviewed? A working hypothesis? A personal theory?

- “Pseudoscience” is too blunt a label: It’s reactive, pejorative, and closes doors.

What we need is a taxonomy—a nuanced way of labeling the epistemic status of a claim without invalidating its potential.

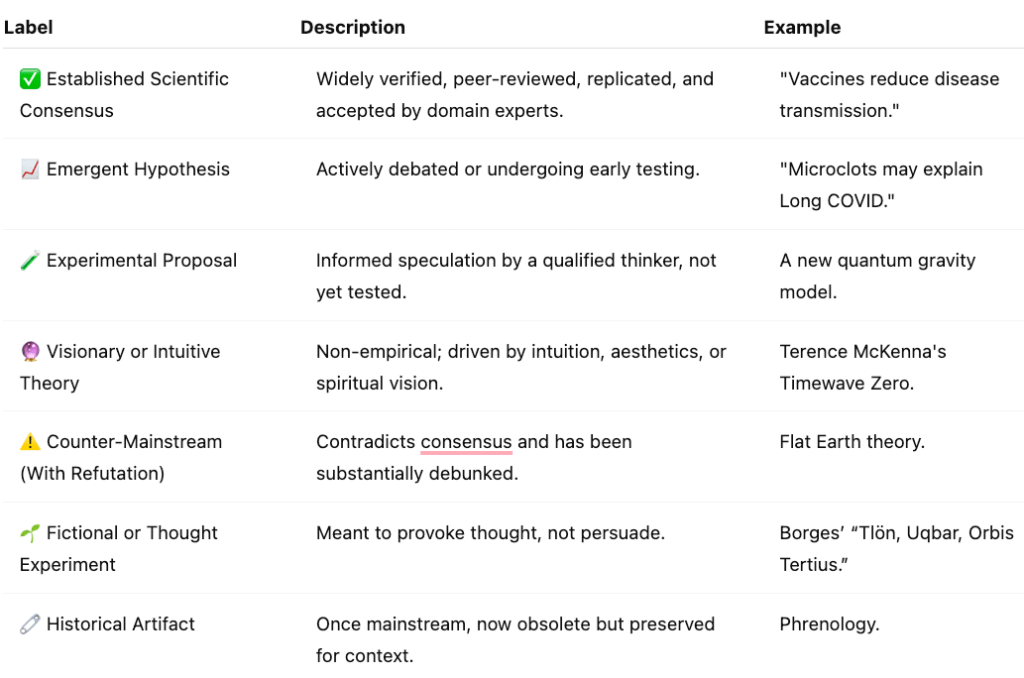

🧾 II. The Framework: Possible Epistemic Labels

Like nutrition facts or Creative Commons licenses, epistemic licenses offer a signal to readers/viewers about the kind of claim being made.

Here’s a draft typology:

| Label | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ✅ Established Scientific Consensus | Widely verified, extensively peer-reviewed, replicated, and accepted by domain experts. | “Water boils at 100°C at sea level.” |

| 📈 Emergent Hypothesis | Actively debated or being tested within the field. Some peer-reviewed support, but not settled. | “Long COVID may be linked to microclots.” |

| 🧪 Experimental Proposal | Informed speculation offered by a qualified thinker; plausible but not yet tested. | A physicist theorizing a new particle model. |

| 🔮 Visionary or Intuitive Theory | Driven by aesthetic, philosophical, spiritual, or experiential insight. Not intended as empirical proof. | Terence McKenna’s Timewave Zero theory. |

| ⚠️ Counter-Mainstream (With Refutation) | Claim directly contradicts scientific consensus and has been substantially debunked. | Flat Earth theory. |

| 🌱 Fictional Framework or Thought Experiment | Designed to provoke thought, not persuade. May use metaphor, imagination, or deliberate fantasy. | Borges’ “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.” |

| 🧷 Historical Artifact | A belief once held widely, now refuted or obsolete, but preserved for cultural or pedagogical value. | Phrenology. |

Each label could come with a badge, color code, and even source links, if hosted on platforms like YouTube, Wikipedia, blogs, or publishing sites.

⚖️ III. How It Could Work in Practice

Let’s take Terence Howard as an example:

Without Epistemic Licensing:

“1×1=2. That’s the truth. Math is broken.”

Audience takeaway: Is he a genius? Is he insane? Should I believe this?

With Epistemic Licensing:

🔮 Visionary Theory

“This is a non-peer-reviewed, personal reimagining of mathematics by Terence Howard. It draws on intuition and metaphysical belief. Not endorsed by mainstream mathematics.”

Audience takeaway: Fascinating. Imaginative. Not verified.

This doesn’t suppress Howard—it honors his expression, while protecting the public from mistaking it for settled truth.

🧭 IV. Guiding Principles

- Transparency, not censorship

– The goal is not to block ideas, but to contextualize them. - Respectful pluralism

– Even wild or mystical ideas deserve space—if they’re not passed off as empirical truth. - Reflexivity

– Mainstream science must also be licensed. Consensus is not infallibility. Every position has a status. - Open revision

– Labels can change. Today’s fringe can become tomorrow’s orthodoxy.

🛠️ V. Implementation Ideas

- Digital platforms like YouTube, Medium, or TikTok could adopt voluntary epistemic labels.

- Journals or blogs might add badges to posts: 🧪 Hypothesis | 📈 Emerging Evidence | 🔮 Speculative.

- Educators could use them to teach students media literacy and epistemology.

Perhaps someday we’ll see:

- A browser extension that overlays epistemic signals on webpages.

- Epistemic APIs that platforms can query to label or classify content.

- Public libraries of speculative ideas that track how fringe theories evolve.

💡 VI. Challenges and Objections

- Who decides the labels?

→ Ideally a mix of transparent, decentralized, peer-based reviews—similar to open-source communities. - Would this stigmatize fringe thinkers?

→ Only if we treat epistemic labels as hierarchies rather than descriptions. The goal is honest signaling, not demeaning. - Is this too idealistic?

→ Maybe. But so was peer review once. So was Wikipedia. Systems can evolve.

🌌 Final Thought

Science has grown up in a world of paper journals and closed-door committees. But knowledge is now performative, viral, memetic.

If we don’t create epistemic infrastructure for this world, we’ll either:

- Repress imaginative thinking, or

- Drown in epistemic chaos.

Epistemic licensing is a third way.

It invites wild minds to speak, while helping audiences to see clearly.

Not every idea has to be true. But every idea should wear its name tag.

🧙🏾♂️

Would you like to turn this into a white paper, a comic strip, a policy proposal, or a satire-infused explainer?

User: White paper.

ChatGPT:

Title: Toward Epistemic Licensing: Reimagining Public Knowledge in the Age of Open Information

Abstract In an age where information is omnipresent but context is scarce, the boundaries between science, speculation, pseudoscience, and myth are rapidly eroding. This white paper introduces the concept of “epistemic licensing” as a scalable framework for labeling the epistemic status of claims in public discourse. By providing transparent, contextual markers for different types of knowledge claims, epistemic licensing aims to enhance epistemic clarity without suppressing creativity, curiosity, or dissent.

1. Introduction: The Crisis of Cognitive Legibility In today’s media environment, a PhD lecture, a viral TikTok theory, and a conspiracy meme often appear side by side, visually indistinguishable. The public lacks tools to differentiate between peer-reviewed knowledge and personal speculation. The term “pseudoscience” has become a blunt instrument, often used not for clarification but for dismissal. A more nuanced framework is needed.

2. Concept Overview: What is Epistemic Licensing? Epistemic licensing is a proposed system of contextual markers that denote the epistemic status of an idea or theory. Like nutrition labels for food or Creative Commons licenses for content, epistemic licenses serve as indicators for the reliability, consensus level, and methodological grounding of claims.

3. Epistemic License Categories

4. Implementation Proposals

- Platforms (YouTube, TikTok, Medium) could adopt voluntary labeling options.

- Educators can train students to critically interpret claims through epistemic lenses.

- Developers could create browser extensions or APIs to flag and contextualize content.

- Open-source, peer-reviewed registries could maintain evolving license attributions.

5. Ethical Considerations The goal of epistemic licensing is not to gatekeep, censor, or shame speculative thinkers. Instead, it aims to:

- Protect public understanding from mistaking performance for proof.

- Offer visibility to creative or visionary ideas without overstating their evidentiary status.

- Respect pluralism while preserving epistemic rigor.

6. Risks and Mitigations

- Risk: Abuse of labels to suppress dissent

- Mitigation: Keep licensing community-driven and transparent.

- Risk: Epistemic relativism (“everything is speculation”)

- Mitigation: Uphold distinctions without hierarchy; consensus is descriptive, not infallible.

- Risk: Oversimplification

- Mitigation: Accompany licenses with metadata, links, and narrative explanation.

7. Conclusion: A Pluralistic Infrastructure for the Knowledge Age We live in an era where knowledge is no longer centralized but performed. In this context, clarity, context, and epistemic humility become more vital than ever. Epistemic licensing offers a pathway to reintegrate creativity with credibility—inviting speculation while protecting truth.

It is not a wall. It is a map.

Appendix: Visual Schema of Epistemic Licenses (To be developed in collaboration with design partners for future iterations.)

The essay titled “Epistemic Licensing Essay” has been drafted to complement the white paper. It expands the core idea in a reflective, narrative form suitable for publication, educational discourse, or intellectual commentary.

Would you like to refine this for a specific platform (e.g. Aeon, Medium, a peer-reviewed journal) or add citations, visual inserts, or personal commentary before sharing it publicly?