In Defense of Sociology.

Intro.

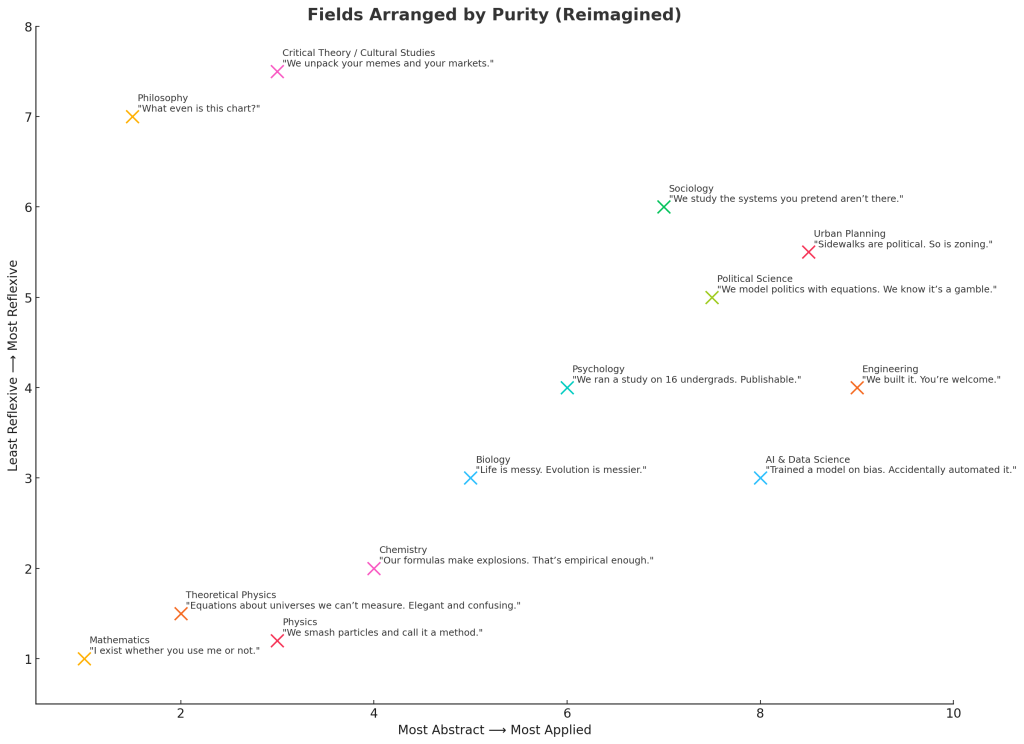

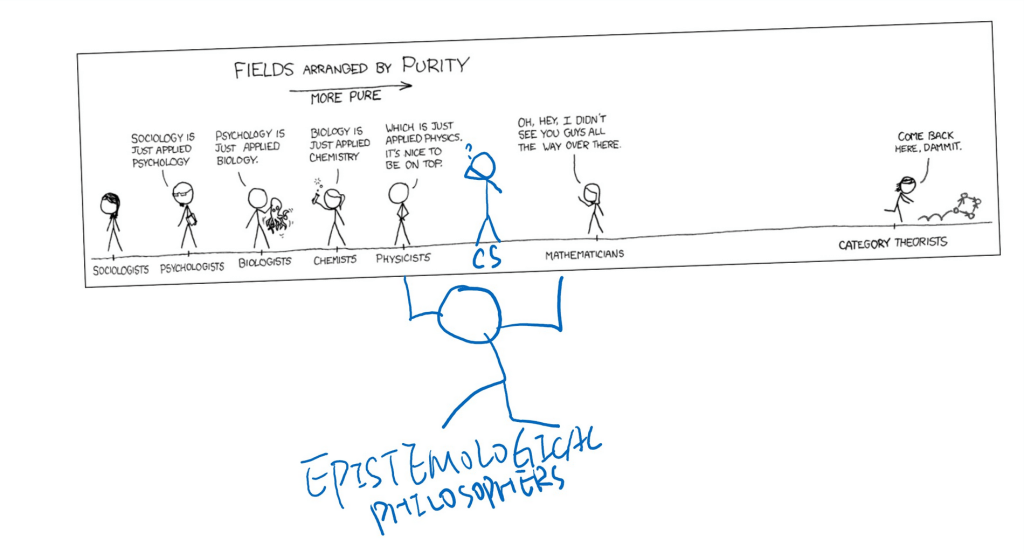

I know that I have repeatedly touched on this topic of in defense of sociology at ad nauseam. I can literally start a whole series on it. This was inspired again by a discussion on the “Fields Arranged by Purity,” which I’ve touched on before and once shared in a post. I couldn’t get ChatGPT to recreate the stick figures and disciplines how I wanted; it would fail at doing so, or make tons of misspelled words.

Not So Pure: In Praise of Sociology, coauthored by ChatGPT 4o.

In Defense of Sociology: Between Abstraction and Life

Sociology often finds itself in a fragile position—simultaneously too abstract for those demanding empirical rigor, and too messy for those seeking clean, formal systems. Caught between the clarity of mathematics and the unpredictability of human life, it is misunderstood not only by outsiders but sometimes by its own practitioners. And yet, sociology remains one of the few disciplines equipped to hold the tension between the subjective and the structural, the personal and the political, the empirical and the interpretive. This essay is a reflection on that unique position.

The now-famous xkcd comic that ranks scientific disciplines by their “purity” captures a prevailing sentiment: that sociology sits at the top of a hierarchy of increasing complexity and decreasing foundational clarity. In this scheme, each field is seen as a dependent elaboration of a more “fundamental” science. Chemistry depends on physics. Biology depends on chemistry. Psychology depends on biology. And sociology, the comic implies, is merely applied psychology. The further a discipline strays from physics and mathematics, the less legitimate it becomes.

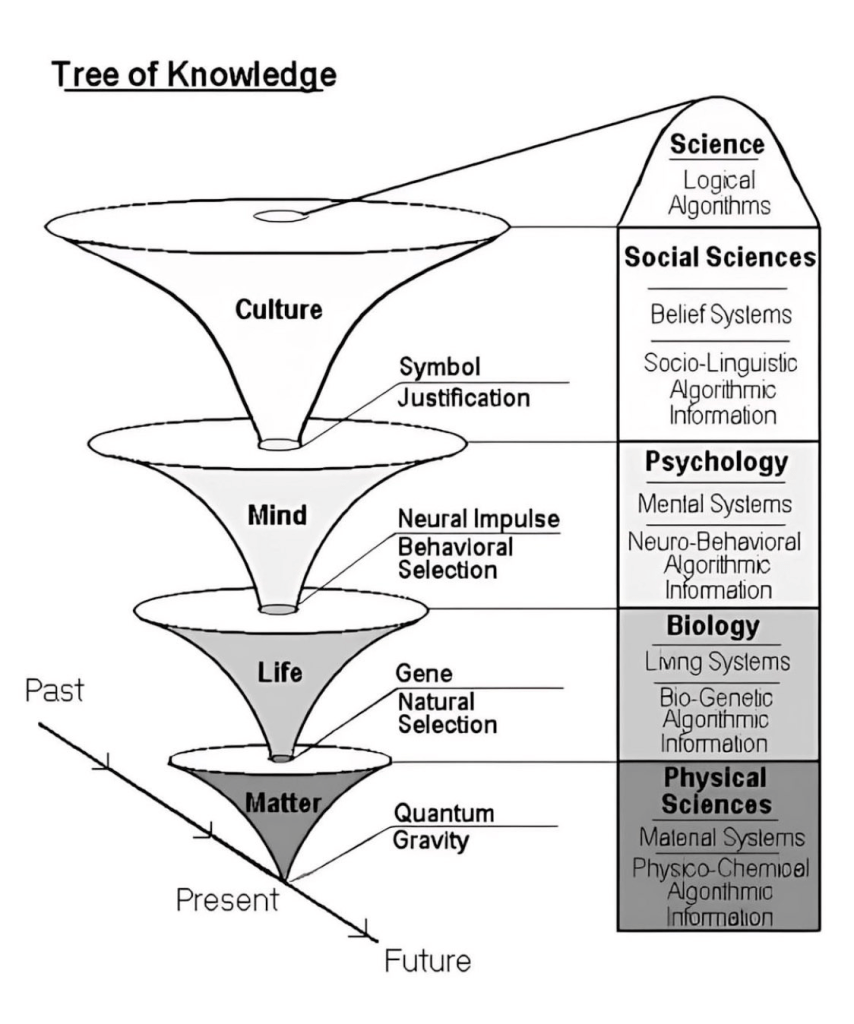

This foundationalist vision is tidy, but it misrepresents the nature of inquiry. Mathematics is indeed abstract, but its abstraction is formal and closed. It begins with axioms and produces theorems that may or may not correspond to the real world. Its truths are internally coherent, but not necessarily empirically meaningful. Sociology, too, is abstract—but not in the same way. Where mathematics abstracts from content to achieve a kind of logical purity, detached from context, relying only on axioms and internal consistency, sociology abstracts from meaning to reveal complexity, rooted in lived experience, history, and social context.

Mathematics defines shapes like triangles or operations like addition that are universally stable and applicable. Its “purity” is in its internal consistency, logic, and lack of dependence on the empirical world. For example, the concept of a “triangle” in geometry exists regardless of whether such a shape is drawn or found in nature. This purity is epistemic isolation—math doesn’t rely on observation to be true.

Sociology, by contrast, develops concepts like alienation or solidarity that shift depending on time, culture, and power. Its concepts—alienation, hegemony, deviance, stratification—are not deduced from first principles. They emerge from engagement with the lived world. They are forged in the mess of history, power, language, and struggle. It doesn’t strive for purity by detaching from the world, but rather dives into complexity. Sociology’s “purity,” if we can even call it that, comes not from detachment, but from an honest engagement with the messiness of human life.

To understand why this distinction matters, we need to consider how sociology works in practice. The abstraction of sociology is porous, always in conversation with reality. It seeks patterns, but knows they are contingent. It builds models, but knows they are incomplete. It theorizes, but remains reflexively aware that its own categories are socially constructed. This is not a failure of science. It is a recognition that not all knowledge obeys the same rules. Sociology does not avoid the world to maintain clarity. It enters the world to understand it, even when that world resists simplification.

One of the most common critiques is that sociology cannot be a science because it deals with the subjective, where meanings are rooted in a narrow view of what science must be. The assumption is that valid knowledge must be objective, quantifiable, and reproducible. But this standard excludes vast realms of human life: belief, identity, memory, love, and fear. These are not noise in the system. They are the system. Sociologists do not study isolated facts. They study patterned subjectivities. They map meaning, power, and norms—not only how they shape us, but how they may overpower and colonize us under the surface of daily life. They ask how reality is socially organized and by whom.

This brings us to a deeper tension: how to study subjective meaning with rigor. Subjectivity is not a flaw in sociology’s method. It is its domain. Ethnography, interviews, discourse analysis—these are rigorous techniques for studying how people make sense of their world. The messiness of these methods does not invalidate them. On the contrary, they reflect the complexity of the phenomena under study. Sociology is not about reducing human behavior to algorithms. It is about honoring the irreducibility of social life, while still seeking intelligibility—a kind of clarity that honors complexity.

This does not mean sociology should reject scientific discipline. On the contrary, the field has produced robust statistical models, longitudinal datasets, and predictive analyses. But it must always balance this with interpretive sensitivity. To demand that sociology conform to the standards of physics is to misunderstand both disciplines. The physicist looks for universal laws. The sociologist looks for situated meanings. Both are doing science. They are simply asking different questions.

For instance, when George Floyd’s murder sparked protests worldwide, it was not biology or chemistry that helped us understand what was happening. It was sociology—of race, of policing, of collective trauma and symbolic justice—that gave us language for the moment. Only a discipline attuned to power, meaning, and social structure could trace the significance of a knee on a neck, and the eruption that followed. In moments like these, sociology does not just interpret the world—it reveals what the world has tried not to see. It reveals the systemic racism long masked by polite narratives of progress. It reveals the unequal distribution of vulnerability, where some lives are hyper-visible and others disposable. It reveals the choreography of authority—how violence is normalized, justified, or rendered invisible in public life. And it reveals the symbolic power of resistance itself, how grief becomes action, and how action reshapes collective meaning.

What followed from Black Lives Matter may not have truly been the best remedy. The momentum it generated was powerful, but its aftermath revealed the limits of symbolic gestures and institutional promises. Still, sociologists—and many non-experts—are doing the hard work of reckoning with the root causes. They are trying to understand how systemic injustice reproduces itself, how public outrage gets absorbed or deflected, and how real change might be imagined beyond the cycle of protest and pacification. The answers are elusive, but the willingness to ask the right questions is a critical first step.

This, too, is sociology’s power: not just to diagnose what has failed, but to insist that understanding must precede transformation. In a world where activism is sometimes reduced to branding and the clickbait economy of outrage, where gestures become hashtags, and structural demands are emptied into viral performance, and justice flattened into metrics, sociology reminds us that no system can be changed without first being made legible. It teaches us that behind every reaction is a structure, behind every symbol a history, and behind every silence a pattern of constraint. And it teaches us to keep asking—not only what must change, but why it hasn’t already.

You cannot challenge racism without first understanding how it was/is embedded in law, culture, policy, and unconscious habits. You cannot dismantle systemic inequality without seeing the mechanisms that reproduce it—tax codes, zoning laws, credentialing systems, and cultural capital. You cannot reform institutions or nations unless you grasp their internal logic, and the broader claims to rationality that justify them, their rules of exclusion, their myths of neutrality. Sociology’s role, then, is to make these systems legible—not just descriptively, but critically. It reveals not only what is, but how it came to be, whose interests it serves, and what alternatives might exist. Without that clarity, transformation remains a slogan, not a strategy.

There is a final irony in the comic’s hierarchy. While sociology is placed at the top, as if it is furthest from mathematical truth, it is also the only discipline that studies all the others in context. It analyzes how science is funded, who gets to be called an expert, how knowledge is institutionalized, and how authority is constructed. In other words, sociology is not just a discipline among others. It is the discipline that allows us to see disciplines as social artifacts. It is the mirror science, turning back on the structure of knowledge itself.

In an era of information overload, ideological polarization, and algorithmic governance, the need for sociological thinking has never been greater. What kind of society ignores how power operates? What kind of citizenry can thrive without understanding the norms they inherit, or the structures that invisibly govern their lives? We do not need more purity. We need more reflexivity. More humility. More attention to the systems of meaning that bind, divide, and entrap us. Sociology does not always provide final answers. But it asks essential questions. And sometimes, that is the more difficult and more necessary task. Sociology can help remedy or reform systems, liberate us from them, or at times even expose how they conquer us under the guise of order, progress, or truth.

To defend sociology is not to claim it is perfect. It is to claim it is indispensable. Not because it mimics the purity of math or physics, but because it dares to study what they cannot: the unruly, constructed, and contested nature of human life.

If physics gives us the equations to predict motion, sociology gives us the language to decode social movements—of people, of power, of memory. When a protest erupts, when a community heals, when silence grips a room after injustice, sociology listens. It traces the unseen wires between us, the rituals we inherit, the categories we live inside. Sociology shows us how we become domesticated by the civilizing process—how norms refine us, institutions shape us, and the pursuit of order tames both our instincts and our possibilities. It teaches us not only to ask “what is true?”

There is, however, one discipline often absent from such hierarchies—perhaps because it is too entangled with the real world to sit still long enough to be ranked. Engineering does not build on sociology in a linear sense, but it builds with it. Where sociology uncovers structures of meaning and power, engineering implements and materializes them—sometimes consciously, sometimes not. Urban design, algorithmic systems, public infrastructure, and environmental technologies all depend on social dynamics to function well or fail justly. Engineering is where theory meets constraint, where abstraction confronts physical form. It is less about understanding the world as it is and more about shaping what comes next. In that sense, engineering is sociology’s pragmatic cousin: they do not speak the same language, but they build in shared spaces.