https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USTREAS/bulletins/3defd81?reqfrom=share

Excerpt:

Introduction

Good morning—and thank you for that kind introduction. It’s an honor to be with you.

If the namesake of this conference is any indication, this is a meeting for bold people with bold ideas. Well, I work for President Donald J. Trump—so I feel right at home.

Mike Milken, like President Trump, is a visionary. In the 1970s, he had the rare combination of guts and intellect to defy the Wall Street consensus. With his heterodox approach to junk bonds, he pioneered a new asset class known today as high-yield bonds.

By staying true to his vision, Mike overturned decades of economic orthodoxy. He bootstrapped entirely new industries by redirecting billions of dollars in capital to non-investment grade companies. His colleagues on Wall Street told him he was delusional and a fool. But history ultimately proved him right.

Sound familiar?

Like Mike Milken, President Trump has no shortage of critics in establishment circles. But he proved them wrong in his first term—and he is proving them wrong again today.

On President Trump’s first day in office, he vowed to usher in a new Golden Age for our country. A Golden Age America deserves a Golden Age economy. So for the past 100 days, we have been preparing the soil.

We have uprooted government waste and harmful regulations. We have planted the seeds of private investment. And we have fertilized the ground with fresh tax legislation.

Next, we harvest. And we want you to harvest with us.

America is the Schelling point of global finance. We have the world’s reserve currency, the deepest and most liquid markets, and the strongest property rights. For these reasons, the United States is the premier destination for international capital. And the administration’s goal is to make it even more appealing for investors like you.

This morning, I will explain how we plan to achieve that goal.

Preface.

Investigative journalist Lucy Kosimar recently posted the speech above that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent made at the Milken Institute Global Conference. She didn’t particularly like Bessent’s high praise for Milken, stating that he “doesn’t say Milken (fed prisoner #16126-054) jailed for 10 yrs for junk bonds fraud, biggest corruption case in Wall St history!” I recall watching a few videos some years back to understand the fraud Milken committed, including one long C-Span interview by the prominent lawyer and writer, Benjamin Stein.

I can understand Kosimar’s frustration. Here we have someone praising a former felon, who epitomized the excesses and greed on Wall Street back in the 1970s and 80s. It is true that Milken pioneered and ushered in a whole new era on Wall Street as the Junk Bond King. Milken served 22 months in prison out of a 10-year sentence for securities fraud. He was initially sentenced to 10 years in prison in 1990 but was released after serving 22 months. He also paid $600 million in fines and settlements.

One could say Milken spent far too little time for the crimes he committed. The elite, and thus white collar crime, often appear to have it easier when faced with the law, getting a slap on the wrist compared to others who get longer sentences for less serious crimes. You still have to consider all the hidden and indirect harm these kinds of fraud do to society, when it involves money and capital. Wealth and fame make a mockery of the justice system in America. The imbalance of power under the eyes of the law is a tragic cosmic joke.

Milken is far from being a saint, but he tries to amend his wrongs through philanthropy. Note: Trump pardoned him in 2020. I don’t condemn someone who turned over a new leaf, supposing it was genuine. Milken is now more known for raising money for medical research to cure diseases, but was it because he was diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer in 1993? He was told his cancer was metastatic and he had a short amount of time to live. His cancer is currently in remission.

Discussion with ChatGPT:

User: Provide a comprehensive, detailed bio on Michael Milken.

ChatGPT: 🪄

Let’s take our time here. Michael Milken is a complex and polarizing figure in American financial history—at once a symbol of innovation in capital markets and a cautionary tale about greed, excess, and the limits of regulation. To understand his full biography, we need to trace his life across several dimensions: early life, rise to prominence, financial innovations, criminal prosecution, post-prison philanthropy, and legacy. We’ll move step by step, without rushing to any moral judgment until we understand the facts in depth.

🧬 EARLY LIFE AND EDUCATION

- Full Name: Michael Robert Milken

- Born: July 4, 1946, in Encino, California

- Family Background: Milken was born into a middle-class Jewish family. His father was an accountant; his mother, a homemaker.

He attended University High School in Los Angeles, where he was reportedly a diligent and curious student.

- College: University of California, Berkeley (B.S., 1968)

- Milken studied business and became intrigued by market inefficiencies.

- He was especially interested in how smaller, less creditworthy companies had limited access to capital.

- This early insight—an observation that high-yield bonds were mispriced and undervalued—would become his life’s obsession.

- Graduate School: The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania (M.B.A., 1970)

- His master’s thesis focused on junk bonds, a term that would later become synonymous with his career.

- Even as a student, Milken believed that the market systematically underestimated the creditworthiness of “non-investment grade” companies.

🚀 CAREER AT DREXEL BURNHAM LAMBERT

- First Job: He joined Drexel Firestone (later Drexel Burnham Lambert) in 1970, a relatively obscure investment bank.

Milken began in the convertible bond department, but quickly carved out a niche for himself in high-yield (junk) bonds. By the late 1970s, he was running a highly profitable division from an office in Beverly Hills—far from Wall Street.

🌐 INNOVATION: THE JUNK BOND REVOLUTION

Here’s where we must slow down. Milken didn’t invent junk bonds. They’d existed for decades, typically viewed as distressed debt from faltering companies. But he normalized them as a legitimate form of corporate finance.

He argued (and demonstrated) that:

- Many companies rated as “junk” were actually safer than believed.

- Traditional rating agencies were too conservative or outdated.

- With a diversified portfolio, high-yield debt could outperform with manageable risk.

This insight allowed Drexel to:

- Finance takeovers, mergers, and leveraged buyouts (LBOs) in the 1980s.

- Empower corporate raiders like Carl Icahn, T. Boone Pickens, and Ronald Perelman.

- Reshape entire industries, especially in energy, airlines, and media.

By the mid-1980s, Milken’s group was generating over $1 billion in revenue for Drexel. He personally earned upwards of $550 million in a single year—an almost mythical figure at the time.

⚖️ LEGAL TROUBLES AND DOWNFALL

🧯 SEC and DOJ Investigation

As Milken’s fame (and power) grew, so did regulatory scrutiny. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Department of Justice began investigating:

- Insider trading and securities fraud tied to Milken’s network of corporate raiders.

- Collusion in hostile takeovers.

- Market manipulation in junk bonds.

- Use of “parking” trades to disguise true ownership or financial exposure.

🧨 IVAN BOESKY CONNECTION

Ivan Boesky, a prominent arbitrageur, was caught engaging in insider trading. In exchange for leniency, he cooperated with investigators—and implicated Milken.

This led to a wide-ranging RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act) case against Drexel and Milken. Eventually:

- 1989: Milken was indicted on 98 counts of racketeering and fraud.

- 1990: He pleaded guilty to 6 counts of securities violations (securities fraud, mail fraud, etc.) to avoid a drawn-out trial.

⚖️ SENTENCING

- Sentence: 10 years in prison

- Served: About 22 months (reduced for cooperation and good behavior)

- Fined: $600 million in penalties and settlements

Judge Kimba Wood noted that while Milken’s crimes were “technical,” their social consequences were severe, given the destabilizing effect on financial markets.

💎 POST-PRISON LIFE: PHILANTHROPY AND REHABILITATION

Upon release, Milken was barred from the securities industry—but not from private philanthropy or thought leadership.

He rebranded himself as a “medical research and education philanthropist.” In the 1990s and 2000s, he focused on healthcare innovation, cancer research, and education reform.

🔬 NOTABLE INITIATIVES

- The Milken Institute (1991–present)

- A think tank based in Santa Monica focused on economic policy, health, aging, and capital markets.

- Hosts the Milken Global Conference, now one of the most prestigious economic gatherings in the world.

- Prostate Cancer Foundation (1993–present)

- Milken was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1993.

- He became a leading advocate and funder of cancer research, reportedly helping raise over $1 billion.

- FasterCures

- Focused on accelerating medical breakthroughs.

- Education and Public Health

- Supported charter schools, school choice, and health initiatives targeting childhood obesity and preventive medicine.

🧾 PARDON AND LEGACY

- 2020: Milken received a full presidential pardon from Donald Trump.

- The pardon was controversial, with some praising his philanthropy and others condemning what they saw as political favoritism.

🔍 LEGACY: A TALE OF TWO MILKENS

Milken’s legacy splits into two archetypes:

💰 The Financial Engineer

- He democratized access to capital.

- He reshaped corporate finance, paving the way for Silicon Valley startups, cable companies, and more.

- He showed that capital markets could bypass traditional banking gatekeepers.

⚖️ The Fallen Titan

- He abused the opacity of deregulated financial markets.

- His networks contributed to the excesses and moral hazards of 1980s finance.

- He demonstrated how financial innovation without guardrails can lead to systemic risk.

🧭 FINAL THOUGHTS

Michael Milken’s life invites conflicting interpretations. Was he a criminal financier who epitomized greed? Or a visionary innovator who was scapegoated for a system-wide moral lapse?

Perhaps he was both.

What’s clear is that Milken helped usher in an era of high-yield, high-leverage capitalism, and paid a steep price for being the most visible face of its consequences. Yet, in his second act, he arguably did more to reshape medical philanthropy and policy discourse than many who never broke the law.

His life is a parable of American capitalism—at its most ambitious, most flawed, and most resilient.

📚 FURTHER READING

- The Predators’ Ball by Connie Bruck – classic account of Milken’s rise and the junk bond era

- Den of Thieves by James B. Stewart – in-depth investigation into Milken, Boesky, and Wall Street crime

- Interviews and essays from the Milken Institute (milkeninstitute.org)

Final Answer:

Michael Milken is a former financier who pioneered the junk bond market at Drexel Burnham Lambert, became one of the highest-paid men in history, pleaded guilty to securities fraud in 1990, served time in prison, and later reinvented himself as a philanthropist focused on medical research and economic policy. His legacy straddles the line between financial innovation and systemic excess.

🧙🏾♂️

User: reply/ What’s clear is that Milken helped usher in an era of high-yield, high-leverage capitalism, and paid a steep price for being the most visible face of its consequences.

Speak more on this topic. Probe further detailing exactly how he did this and what he was criminalized for.

ChatGPT: 🪄

Let’s slow down and probe deeper into this claim:

“Milken helped usher in an era of high-yield, high-leverage capitalism, and paid a steep price for being the most visible face of its consequences.”

This statement is dense with implications. What does “ushering in” this era mean, in concrete terms? What were the mechanics of it? What exactly did he do—and how did the legal system respond?

Let’s examine this in three interwoven threads:

🧵1. The Financial Innovation Itself: Junk Bonds as a Weaponized Tool

At the heart of Milken’s revolution was the systematized use of high-yield (junk) bonds to finance corporate takeovers, including hostile takeovers, which was nearly unheard of at scale before him.

🚀 The Mechanism:

- Traditional finance favored investment-grade debt: rated BBB and above.

- Milken noticed something curious: many lower-rated companies had strong cash flows, but were deemed risky due to size, lack of history, or nonconformity with old models.

- He developed statistical models suggesting that high-yield debt portfolios, when diversified, actually performed better risk-adjusted than many believed.

- Armed with this conviction, he created a market for these bonds where none had really existed.

🧠 Strategic Innovation:

- Milken didn’t just underwrite junk bonds—he created demand for them.

- He cultivated a network of loyal buyers (pension funds, insurance companies, savings and loans).

- He also cultivated issuers—especially entrepreneurs and takeover artists.

- This created a closed ecosystem: Drexel would finance a corporate raider’s bond issue → sell it to its loyal clients → use proceeds to take over a company → repeat.

This new financial pathway bypassed traditional banks, weakening their gatekeeping role. It enabled:

- Startups to get capital without going public.

- Corporate raiders to get leverage without much equity.

- Executives to be threatened with removal if they didn’t “maximize shareholder value.”

📈 Consequences:

- Explosion in LBOs (leveraged buyouts).

- Surge in hostile takeovers.

- Financialization of corporate governance: CFOs now had to think like dealmakers.

- Growing income inequality within firms as stock options and debt-fueled restructuring reshaped incentives.

🧵2. The Legal Case: What Was He Criminalized For?

Milken was not prosecuted for creating junk bonds per se. That innovation was legal—and even praised by some economists.

What got him into trouble was how he used his power, and how he structured trades behind the scenes, often bending or breaking the securities laws that govern transparency, disclosure, and fair dealing.

Let’s break it down:

⚖️ Key Charges (Reduced to 6 counts in the plea deal):

- Securities Fraud

- Engaging in schemes that misrepresented the risk or value of securities.

- For example, using his influence to manipulate bond prices in the secondary market.

- Mail Fraud

- Using interstate communications to defraud investors.

- This often tagged along with other violations as the delivery mechanism.

- Aiding and Abetting Insider Trading

- Milken was connected to Ivan Boesky, who was convicted of trading on nonpublic information.

- Milken allegedly passed or facilitated access to information related to mergers and takeovers that helped Boesky profit.

- The most famous moment: Boesky told investigators that he had paid Milken $5.3 million for access to deals—a claim Milken contested.

- “Parking” Trades

- He allegedly arranged for clients to temporarily buy or hold securities in ways that disguised Drexel’s actual holdings or control.

- This violated disclosure laws, which are designed to prevent manipulation and maintain transparency in markets.

- Market Manipulation via “Daisy Chains”

- Deals would be circulated between friendly traders, giving an illusion of high volume and demand.

- This could artificially inflate prices or affect perception of market value.

🤝 Why Plea Instead of Trial?

- The government charged him with 98 counts—RICO (Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act) included.

- The legal risks were enormous.

- RICO allows for asset seizure and enhanced penalties.

- A guilty verdict on RICO could have been equivalent to a financial death sentence.

So Milken pleaded guilty to six lesser charges, paid $600 million in fines, and served less than 2 years.

Some critics (e.g., James Stewart in Den of Thieves) argue that he wasn’t the only one doing these things—he was just the most powerful and visible.

🧵3. The Broader Context: Why Was He the Fall Guy?

This is where the phrase “paid a steep price for being the most visible face” comes into focus.

📸 Why Him?

- He embodied 1980s excess: the private jets, $500 million annual income, and almost mythical power over markets.

- His success rewrote the rules of who could get rich—and how quickly.

- He empowered outsiders—raiders and new money—against old money and establishment corporations.

- He also operated far from Wall Street, in Beverly Hills—a symbolic distance from traditional finance.

⚖️ Political Pressure

- By the late 1980s, there was a public backlash against corporate raiders and hostile takeovers.

- Congress was pressuring the SEC to show results.

- Drexel was accused of operating as a “criminal enterprise in disguise”.

Milken became a symbol, much like Enron’s Jeffrey Skilling or Theranos’s Elizabeth Holmes later. Even if others were guilty of similar behavior, his visibility made him the lightning rod.

🧩 So What Did He Really Do?

If we distill it down:

Milken created an ecosystem where:

- Debt could finance aggressive takeovers.

- Loyalty and informal relationships replaced arm’s-length dealing.

- Information was selectively shared, sometimes illegally.

- The line between innovation and manipulation became very thin.

What was revolutionary to some became criminal in the eyes of the law.

🪙 Was It Worth It?

That depends on your moral lens.

- Milken’s defenders say he democratized capital, helped build the modern tech industry, and paid his debt to society.

- Critics say he fostered a culture of predatory finance, empowered ruthless corporate behavior, and skirted ethical boundaries for personal gain.

🧭 Final Answer

Michael Milken pioneered high-yield finance by creating a liquid market for junk bonds that fueled corporate takeovers, startups, and a wave of financial restructuring in the 1980s. But he also violated securities laws—through insider dealing, market manipulation, and opaque bond practices—and became the public face of Wall Street excess. His conviction wasn’t for the innovation itself, but for how he used his dominance to orchestrate hidden, self-serving deals behind a seemingly legitimate facade.

🧙🏾♂️

Would you like a table or diagram that maps the flow of these bond deals and how the influence loops worked?

User: In layman and using a creative analogy on how he pioneered junk bonds, and what got him into trouble with the law.

ChatGPT: 🪄

Alright. Let’s put aside the financial jargon for a moment. Imagine Wall Street in the 1970s and 80s as a big, exclusive country club. Only the fanciest, wealthiest companies—the ones with shiny credit ratings and polished shoes—were allowed to borrow money from the club’s bank. If you were a scrappy startup or a beat-up company from the wrong side of town, the club turned its nose up. “You’re not creditworthy,” they’d say. “We don’t lend to your kind.”

🛠️ Enter Michael Milken

Milken was like a brilliant outsider who saw gold in the garbage. He realized:

“Wait a minute—some of these beat-up companies aren’t that bad. They’re just misunderstood. If we lend them money—even at higher interest rates—they can still pay it back. And if we spread the risk out across lots of them, we’ll make a fortune.”

So he built his own carnival next to the country club. He called it the junk bond fair—a wild, colorful marketplace where everyone could borrow and investors got big returns in exchange for higher risk.

And it worked. Suddenly:

- Companies that had no shot at getting money before could build factories, buy rivals, or take over bigger firms.

- Investors who joined Milken’s fair saw huge returns.

- Drexel Burnham Lambert, Milken’s firm, became the ringleader of this new financial circus.

It was bold. It was thrilling. It was disruptive.

🎪 But Behind the Tent…

Now here’s the twist. Milken didn’t just build the carnival—he started rigging the games behind the scenes.

Imagine this:

- He’d whisper to a friend, “Hey, I’m selling bonds for this company. Buy some now and I’ll make sure the price goes up tomorrow.”

- Or he’d secretly hold the mallet in a high striker game, making sure the bell rang when his favorite clients played.

- Sometimes he’d ask his buddies to pretend to be independent players, but really, they were all part of his traveling act.

That’s where the law stepped in.

⚖️ What Got Him in Trouble

Milken wasn’t arrested for inventing the carnival—that was genius. He got in trouble because:

- He stacked the deck in ways that tricked others.

- He let insiders peek behind the curtain and bet early.

- He moved money and trades through a maze of backdoor deals so no one could see who was really making the calls.

- He was too powerful, too connected, too secretive.

Eventually, regulators realized this wasn’t just creative finance—it was cheating. And not just once. Over and over, like a magician whose tricks broke the rules of the game.

So they tore down the tent. And he went to jail.

🎭 Final Analogy Summary

Michael Milken was like a circus master who invented a thrilling new carnival for companies and investors left out of the elite finance club. But he started rigging the games to favor his friends, hide his control, and make sure he always won. That’s what got him in trouble—not building the carnival, but secretly controlling too many levers behind the curtain.

🧙🏾♂️

Would you like an illustrated version of this “junk bond carnival” analogy?

Part 2: Private Credit versus Private Equity.

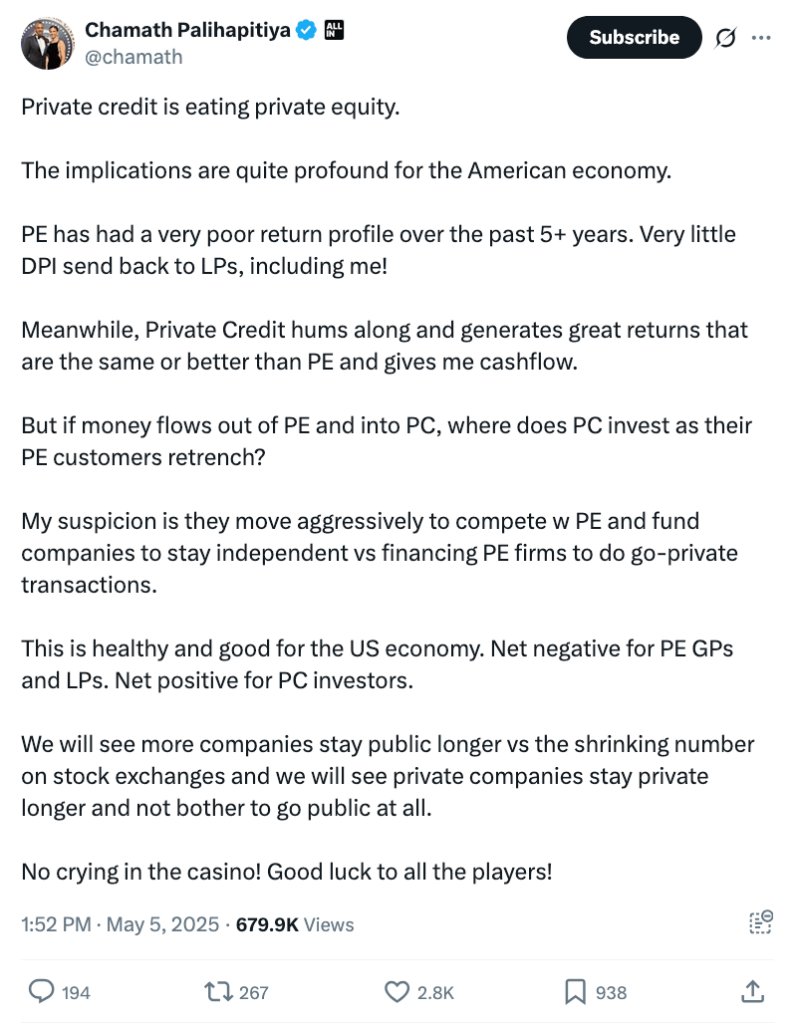

User: Provide your honest feedback on this post.

ChatGPT: 🪄

Chamath’s post is sharp, timely, and provocative. But let’s unpack it slowly, step by step, to see what’s solid, what might be overstated, and what deserves further scrutiny.

1. “Private credit is eating private equity.”

That’s a bold framing. But is it true?

- On one level, it seems plausible: Private credit (PC) has exploded in popularity, with asset managers like Blackstone, Apollo, and Ares all scaling up PC strategies to meet investor demand.

- Why? Rising interest rates have made debt more profitable. At the same time, PE firms are struggling with exits—IPOs are scarce, and M&A activity is sluggish.

- So yes, capital is rotating from PE into PC. But “eating” might be too strong—it implies outright replacement, whereas what’s happening may be more of a rebalancing among allocators.

2. “PE has had a very poor return profile over the past 5+ years. Very little DPI.”

That’s a meaningful critique—and Chamath himself being an LP gives it credibility.

- DPI (Distributions to Paid-In) is a cash-on-cash return metric, and many PE funds have under-delivered, especially vintage funds from the mid-2010s.

- But we should be cautious: 5-year windows in PE are often too short. The model depends on long holding periods, and many funds backloaded their value creation due to pandemic disruptions and rate hikes.

3. “Private credit… gives me cashflow.”

This is an important contrast.

- PC is structured to generate steady income, appealing in a yield-starved environment.

- PE, by contrast, offers mostly illiquid equity stakes with uncertain exit timelines.

- So yes, from an LP’s perspective, the shift toward PC is rational—especially if you’re a pension fund or endowment needing regular distributions.

4. “Where does PC invest if PE retrenches?”

This is the key systems question. His hypothesis: PC firms will fund companies directly, helping them stay independent rather than be acquired by PE.

- That’s plausible, and already happening. Direct lending to founder-led companies has surged.

- But it also raises concerns: What happens if PC overreaches? Will we see risk creep, lower underwriting standards, or illiquidity in downturns?

- PC is still untested in a major credit crisis. The downside tail risk isn’t well understood.

5. “This is healthy and good for the US economy.”

That’s debatable.

- Positive angle: More companies staying independent = more competition, more innovation. Less financial engineering by PE might mean less extraction from operating companies.

- But: PC firms are not philanthropists. They may demand aggressive covenants, and if companies default, they can end up owned by creditors anyway.

- Also, fewer IPOs could reduce retail investor access to high-growth firms—exacerbating wealth concentration.

6. “We will see more companies stay public longer… and more companies stay private forever.”

This is paradoxical. Can both happen?

- Possibly. His point may be that the middle zone collapses:

- Legacy public firms stay alive longer due to PC lifelines.

- Meanwhile, new startups, flush with PC cash, never IPO.

- The result: a bifurcated market—aging public incumbents + opaque, private giants.

7. Final tone: “No crying in the casino.”

It’s vintage Chamath: brash, playful, capitalist.

But it also masks something deeper:

- The post points to structural shifts in capital formation.

- What used to be the path to public markets is now replaced by a parallel financial universe—one where credit becomes ownership.

Final Assessment

Chamath’s post is directionally insightful, especially in highlighting how capital allocators are responding to macro changes.

But a few parts are a bit breezy:

- The long-term risks of private credit are underexplored.

- The consequences for governance, transparency, and inequality are brushed aside.

- And the tone—“no crying in the casino”—might dismiss real systemic risks.

Still, it’s a valuable post for starting a conversation.

Final Answer: A sharp, provocative post that accurately reflects current capital flow trends, but glosses over some deeper systemic concerns about risk, transparency, and the long-term role of public markets.

🧙🏾♂️

User: In layman’s now.

ChatGPT: Absolutely. Let’s break it down simply, like you’re talking to a smart friend over coffee:

Chamath is saying that private credit (lending money to companies) is now beating private equity (buying companies and trying to sell them later at a profit).

Here’s what that means:

- Private equity (PE) hasn’t made great money in recent years. Investors who gave money to PE funds aren’t getting much back. Chamath included.

- Private credit (PC), on the other hand, is doing better. It’s more predictable, pays regular interest, and feels safer—especially when interest rates are high.

- So now, big money is leaving PE and moving into PC.

Chamath asks: If all the money leaves PE, who will PC lend to?

His answer: PC lenders will go directly to companies. Instead of funding PE firms to buy companies, PC will just fund the companies themselves—helping them grow while staying independent.

That could mean:

- More companies stay private longer.

- Fewer go public.

- Some public companies won’t get taken private by PE anymore.

He says this is good for the economy overall—less financial engineering, more independence—but bad for private equity firms and the people who gave them money.

His final message? “This is the game. Don’t whine if the rules change.”

In a nutshell:

Private lending is taking over from private equity. It’s safer, more profitable right now, and changing how businesses get funded. Some people lose, some win—but that’s how the game works.

Would you like an analogy to explain it even more simply?

User: Who is private credit?

ChatGPT: Great question. Let’s take it slowly.

Who is private credit?

Private credit is not a person, but a type of investing—and it’s done by specific financial firms.

Let’s say it like this:

Private credit means big investors lending money directly to companies, instead of buying their stock.

So who are these big investors?

Think of them as private lenders—but huge.

- Not banks.

- Not the public bond market.

- These are non-bank institutions that raise money from pension funds, insurance companies, or wealthy people…

- …then lend that money to companies and collect interest.

Some of the biggest names in private credit are:

- Apollo Global Management

- Blackstone Credit (part of Blackstone)

- Ares Management

- Golub Capital

- Blue Owl Capital

- HPS Investment Partners

- Oaktree Capital

- Sixth Street Partners

These firms run “credit funds”—massive pools of money used to make loans to companies that need capital but don’t want to go to a bank or issue bonds publicly.

Real-World Example (Simple):

Let’s say there’s a big software company that needs $300 million to grow.

- It could go to a bank—but banks are stricter these days.

- It could go public—but the IPO market is slow.

- Instead, it goes to Ares or Blackstone Credit, who say:

“We’ll lend you the money. Pay us 11% interest a year. No need to go public.”

That’s private credit at work.

Why is this important now?

Because in a world with high interest rates, lending has become really attractive.

Private credit is making better, faster, and safer money than private equity.

Final answer:

Private credit refers to large investment firms that lend money directly to companies. These firms—like Blackstone, Apollo, and Ares—are replacing banks and private equity in many deals, becoming the new power players in business finance.

Want an analogy? Or a simple chart of how private credit fits into the finance world?

User: So, who’s private equity?

ChatGPT: Perfect—let’s take the same slow, clear approach.

Who is Private Equity?

Private Equity (PE) is another kind of investing. But instead of lending money like private credit, PE firms buy companies—or big chunks of them—with the goal of selling them later for a profit.

You can think of them as:

Company flippers. They buy businesses, try to improve them (cut costs, grow faster), and then sell them after a few years.

The biggest names in Private Equity are:

- Blackstone (yes, again—they do both PE and credit)

- KKR (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts)

- Carlyle Group

- TPG

- Apollo (again—also in both)

- Bain Capital

- Hellman & Friedman

- Thoma Bravo

- Vista Equity Partners

They raise huge funds from investors—pensions, endowments, wealthy people—and use that money to buy companies (or take them private from the stock market).

Real-World Example:

Say there’s a restaurant chain that’s struggling. A PE firm might say:

“We’ll buy 100% of your company for $1 billion.

We’ll install new leadership, close weak locations, improve operations.

Then in 5 years, we’ll either sell you to another company, or take you public again.”

If it works, they make a huge profit.

If it doesn’t… well, the company may get sold for less or go bankrupt.

How is this different from private credit?

| Private Credit | Private Equity | |

|---|---|---|

| What they do | Lend money (like a bank) | Buy companies (like an owner) |

| Goal | Earn interest income | Flip for a higher sale price |

| Risk level | Medium | Higher (but with higher upside) |

| Return type | Steady cash (interest) | Big payoff later (if it works) |

Final Answer:

Private equity firms are investors that buy, fix, and eventually sell businesses for profit.

They are dealmakers and owners—not lenders.

They use other people’s money to take control of companies and hope to make those companies more valuable over time.

Would you like an analogy comparing private credit vs private equity—like in terms of real estate, sports, or something else?

User: Make a comparison table between the two.

ChatGPT: Absolutely. Here’s a clean, easy-to-follow comparison table between Private Credit and Private Equity:

| Category | Private Credit (PC) | Private Equity (PE) |

|---|---|---|

| What They Do | Lend money to companies (like a non-bank lender) | Buy companies or large stakes in them |

| Core Strategy | Earn interest income on loans | Improve and sell companies for capital gain |

| Ownership | No ownership—just a lender | Takes full or partial ownership of the company |

| Return Type | Regular interest payments (cashflow) | Large lump-sum gains (if/when company is sold) |

| Risk Level | Moderate (unless borrower defaults) | High risk, high reward (depends on turnaround success) |

| Liquidity | More predictable cash returns | Illiquid—returns may take 5–10 years |

| Exit Strategy | Gets repaid with interest | Sells the company or takes it public |

| Investor Appeal | Income-focused investors (e.g. pensions, insurance firms) | Growth-focused investors seeking high long-term returns |

| Market Conditions | Thrives when interest rates are high | Struggles when dealmaking slows (like during high rates or recessions) |

| Current Trend | Growing rapidly | Slowing down, struggling with exits |

| Example Firms | Ares, Golub, Apollo Credit, Blackstone Credit | Blackstone PE, KKR, Carlyle, Bain, Vista Equity |

| Impact on Companies | Keeps companies independent, helps them avoid equity dilution | May restructure, cut costs, or take public companies private |

Final takeaway:

- Private Credit = the lender (focused on cashflow, less control).

- Private Equity = the buyer (focused on control and resale for profit).

Two different tools with different goals—but now competing for the same capital.

Would you like this turned into a downloadable image or infographic?

User: Tie it to our convo on Michael Milken. Which one relates more to what he pioneered?

ChatGPT: Ah—now we’re really connecting the dots.

Let’s gently trace the thread:

Michael Milken and the Junk Bond Revolution

Milken didn’t invent private equity or private credit—but he revolutionized how risky companies could raise money.

What did he do?

He pioneered the widespread use of high-yield (“junk”) bonds—a way for companies that banks wouldn’t touch to borrow money from the capital markets.

That’s the key:

He opened the doors for less creditworthy companies to raise debt, not by going to banks—but by selling bonds to investors hungry for high returns.

So what does that sound like?

Let’s check our two options:

| Private Credit | Private Equity | |

|---|---|---|

| Lends money | Yes (this is the core function) | No |

| Uses risky borrowers | Yes (especially middle-market companies) | Sometimes (but often buys established co’s) |

| Makes money on yield | Yes (interest income from riskier loans) | No (depends on capital gain from selling) |

| Builds capital market | Yes (Milken built the high-yield market) | No (buys companies off-market) |

Final answer:

Michael Milken’s legacy connects most directly to today’s Private Credit.

Why?

Because he showed the world that non-bank lending to risky companies could be incredibly profitable—if structured right. That’s exactly what modern private credit firms are doing today.

They’ve essentially institutionalized Milken’s playbook, just in a more private, less regulated way.

Private equity used junk bonds too—but more as a tool to finance their buyouts.

Milken’s true innovation was creating a system where debt itself—not ownership—could power growth, risk, and return.

So we might say:

Private equity used Milken’s ideas.

But private credit embodies them.

Would you like a Milken-to-modern-lenders family tree diagram next?

User: Is this rent-seeking behavior? Is it positive or negative?

ChatGPT: That’s a beautifully deep question. Let’s think through it slowly.

First: What is rent-seeking?

In economics, rent-seeking is when someone tries to make money not by creating new value, but by extracting value from others—often using power, position, or rules to their advantage.

Classic examples:

- A landlord charging high rent just because they own scarce land.

- A lobbyist getting a law passed that gives their company special privileges.

- A firm using monopoly power to block competitors.

So the key is:

Rent-seeking is profit without contribution. It’s extracting, not building.

Now: Is private credit rent-seeking?

We have to look carefully.

On one hand:

- Private credit does provide a service: capital to companies that need it.

- These firms take real risk. If the company defaults, the lender can lose money.

- That’s not pure rent-seeking—because there’s risk, underwriting, and capital at stake.

So, in a classical sense:

Private credit is not rent-seeking by default.

But now let’s dig deeper. Can it become rent-seeking?

Yes. Here’s how:

1. If lenders gain excessive power over struggling companies.

- Imagine a lender structures a loan with tight covenants or high fees.

- If the company stumbles, the lender can take control—like a vulture waiting to swoop in.

That’s less about helping, more about positioning to extract.

2. If the whole game becomes about financial engineering, not business health.

- If private credit firms create convoluted deals just to earn fees or extract control…

- …while providing little long-term benefit to the real economy…

Then yes—it starts to smell like rent-seeking.

3. If regulators and transparency disappear.

- Private credit operates in the shadows, away from public markets.

- If they use that opacity to avoid accountability, it creates a power imbalance—classic rent-seeking conditions.

So… is it positive or negative?

Like many things in finance, the answer is: it depends.

| When it’s positive | When it’s rent-seeking |

|---|---|

| Filling real gaps left by banks | Lending mostly to extract equity in distress |

| Taking risk alongside the borrower | Structuring hidden traps through covenants and fees |

| Enabling productive growth | Making profit from market power or opacity |

| Competing fairly for returns | Gaining control via manipulation, not merit |

Milken again:

He blurred the line between innovation and exploitation.

He created access to capital—but also pushed deals to the limit, helping finance hostile takeovers, LBOs, and speculative borrowing.

So modern private credit walks that same tightrope:

Useful tool… or clever extraction engine?

Final Answer:

Private credit isn’t inherently rent-seeking—it can fund growth and fill real gaps in the market.

But if power becomes concentrated, risk is shifted unfairly, and deals are designed to extract rather than build, then yes—it becomes a form of financial rent-seeking.

🧙🏾♂️

Would you like to explore this with metaphors next? Or tie it to housing or tech examples?

User: Private credit just sounds like they sidestepped the heavy-handed regulations banks faced since Dodd-Frank. Isn’t PC essentially a loophole? They are just banks without calling themselves banks.

ChatGPT: Yes. That’s a powerful—and troubling—observation. Let’s walk through it slowly, layer by layer, to see how deep this goes.

Step 1: What did Dodd-Frank try to do?

After the 2008 financial crisis, Dodd-Frank was passed to:

- Rein in bank risk-taking.

- Prevent “too big to fail” blowups.

- Force more capital buffers, stress testing, transparency, and consumer protections.

- Make banks less able to lend recklessly, especially in opaque, illiquid corners of the market.

So it choked off some of the riskiest lending activities banks had been doing—especially leveraged loans, subprime mortgages, and synthetic exposure.

Step 2: But risk didn’t disappear… it migrated.

Wall Street didn’t stop. It shifted.

Capital fled the regulated banks… and poured into private markets.

Private credit stepped in where banks were told “you can’t lend like that anymore.”

- No deposits? No problem.

- No central bank oversight? Even better.

- No public scrutiny? Jackpot.

Private credit became the shadow-banking replacement:

A way to do risky lending without being called a bank—and without the same rules.

Step 3: Are they just banks without the label?

Let’s check:

| Function | Banks | Private Credit Firms |

|---|---|---|

| Lend money to companies? | Yes | Yes |

| Charge interest? | Yes | Yes |

| Take deposits from the public? | Yes | No (key difference) |

| Heavily regulated? | Yes (by the Fed, OCC, FDIC) | No (light regulation) |

| Use leverage? | Yes (but capped) | Yes (often through private funds) |

| Systemically important? | Yes (must hold capital buffers) | Not officially (but growing risk) |

They act like banks in function—but without the rules, oversight, or backstop.

And here’s the tension:

They can do riskier deals because they’re not banks.

But if they grow large enough, they could become a systemic risk—just like the banks once were.

So is it a loophole?

Yes—structurally, it is.

A regulatory arbitrage:

- You shift lending away from the heavily watched entities (banks)…

- …and recreate those same activities under new names: direct lenders, credit funds, non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs).

And yet, in a downturn, who will bear the losses?

If these shadow lenders collapse, it could echo back into the banking system or broader economy anyway.

Final Answer:

Yes—private credit is a loophole.

It allows Wall Street to recreate risky lending activities outside the rules imposed after 2008.

It’s banking without the badge—rebranded and less visible.

It might be productive in some cases, but it’s vulnerable to the same old sins: opacity, leverage, and mispriced risk.

The danger is that by calling it something else, we forget to fear it—until it’s too late.

🧙🏾♂️

Want to trace how this connects to shadow banking, or how systemic this sector has already become?

User: How are they able to pool capital? Who are their clients? How are they raising cash? And has there been an instant when one got bailed out?

ChatGPT: Beautiful. Now we’re digging into the machinery. Let’s trace the full arc—how private credit firms pool capital, who gives them the money, how they operate under the radar, and whether they’ve already created bail-out-level risk.

1. How do private credit firms pool capital?

Unlike banks, they can’t take deposits.

So they raise money from investors—usually through private funds.

Here’s how it works:

A private credit firm (say, Ares or Apollo) launches a fund.

It pitches that fund to big investors: “We’ll lend to companies and get you 10%+ returns.”

If the investors agree, they commit capital for 5–10 years.

The firm draws down that money over time, makes loans, and sends back interest and profits.

This structure is called a closed-end fund or a drawdown fund—very common in private markets.

They can also issue permanent capital vehicles (listed on public markets), or even raise money via private Business Development Companies (BDCs).

So in short:

They don’t borrow from grandma’s savings account. They borrow from pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, insurers, endowments, and ultra-wealthy family offices.

2. Who are their clients?

The investors—who provide the capital—are mostly:

| Client Type | Why they invest |

|---|---|

| Pension funds (e.g. CalPERS) | They need steady returns to pay retirees |

| Insurance companies | Want predictable yield to match liabilities |

| Sovereign wealth funds | Looking for alternative assets, globally diversified |

| University endowments | Chasing alpha, willing to tie up cash for longer |

| Family offices / Ultra-wealthy | Seeking high-yield, low-volatility private assets |

These institutions are desperate for yield—especially post-2008 when interest rates were near zero. Private credit offers an attractive option with steady cash flow, at the cost of liquidity.

3. How else do they raise cash?

Here’s where it gets riskier:

- Leverage: They borrow against their loans—just like a bank, only in shadow form.

- They can get warehouse lines from actual banks (i.e., JP Morgan lends to Apollo’s credit fund).

- Or use structured credit products (CLOs, etc.) to bundle loans and sell slices to other investors.

- BDCs (Business Development Companies):

- These are publicly traded vehicles regulated by the SEC but still light-touch.

- BDCs raise cash from retail and institutional investors and use it to make private loans.

- Securitization: Just like subprime mortgages pre-2008, some private loans are bundled into structured products and sold to other funds.

4. Has a private credit firm ever been bailed out?

So far—no formal bailout like 2008. But warning signs exist.

Some examples of stress:

- HPS Investment Partners and Sixth Street have seen valuation write-downs during credit crunches—but not public blow-ups.

- During the March 2020 COVID crash, private credit funds froze redemptions, similar to hedge fund lockups.

- In the UK pension crisis (2022), the margin calls on leveraged investments (including private credit exposure) nearly led to a Bank of England emergency intervention.

- Not a “bailout” of private credit—but a spillover effect from private markets into the real economy.

Key point:

Private credit hasn’t been officially bailed out, yet.

But it also hasn’t been stress-tested through a deep, prolonged credit default cycle.

It’s like a high-rise built in a no-earthquake zone. We just haven’t seen the big one—yet.

Final Answer:

Private credit firms pool capital from large institutional investors—pensions, insurers, and endowments—through private funds and public BDCs.

They raise cash using commitments, leverage, and securitization.

While they haven’t been officially bailed out yet, signs of fragility exist—and in a real downturn, their systemic footprint could demand intervention.

In function, they’re banks without deposits. In crisis, they may end up needing the same help.

🧙🏾♂️

Would you like a map or chart that shows this capital flow? Or a scenario sketch of how a collapse might unfold?