Description: The Steamboat Institute, in partnership with the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership, is proud to present a compelling debate on the following resolution: “Be it resolved, the U.S. federal government should make reducing the national debt a fiscal priority.” Arguing the affirmative is Steve Moore, Senior Visiting Fellow in Economics, The Heritage Foundation. Arguing the negative is Stephanie Kelton, Bestselling Author of The Deficit Myth; Professor of Economics and Public Policy, Stony Brook University.

Preface.

There was a recent debate between Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Economist Stephanie Kelton and the more libertarian leaning Economist Steve Moore. I found out about it through Kelton’s Substack, and I thought it would be an opportune time to better understand her stance and the disagreement in economics as it relates to fiscal and monetary policy between the two schools of thought. It’s an opportune time indeed when leveraging ChatGPT, which can dissect the debate much clearly for me, of the claims and arguments being made, and using it to expand my own knowledge.

Now, the disclaimer. Leveraging LLMs/AI will not be picturesque perfect because one can fall victim to the Dunning-Kruger effect. But this effect can be somewhat nullified or reduced with epistemic humility, you don’t accept answers from anyone, including machines, at face value, and yet still leverage AI to probe deeper and question the assumptions and claims made by the experts. That’s the role of the philosopher who veers into all subjects and tries to comprehend them despite not being an all-knowing expert in such niche or specialized topics. Philosophers are great generalists who question deeply underlying assumptions and ask the right questions. As I’ve said before, “Philosophy is the art of asking questions.”

Discussion with ChatGPT 4o. (custom instruction).

User: I want you to summarize and break down a long transcript. I will share it in parts.

ChatGPT: Absolutely, go ahead and share the first part of the transcript when you’re ready. I’ll break it down and summarize it thoroughly as we go.

User: (copy and paste transcript).

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Alright, let’s pause and take this step by step. This is already rich with context and implications, even from the first few paragraphs. Let’s peel it back.

Foundational Observations

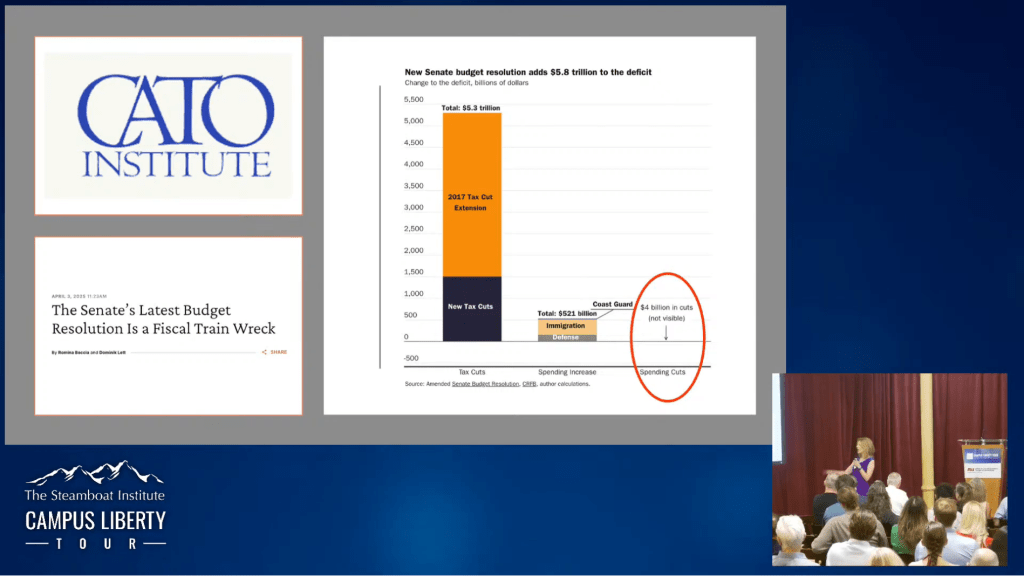

Let’s start small. Steve Moore is speaking. He’s an economic commentator and policy advocate, known for a fiscally conservative perspective. He frames the discussion with a personal anecdote — he arrived in Washington in 1984 and worked under Ronald Reagan, a name that already sets the tone. Reagan is often invoked in fiscal conversations as a benchmark for conservative economic principles, whether one agrees with them or not.

Moore recalls the introduction of the first $1 trillion federal budget in 1985. He calls it something they “weren’t proud of,” which is telling — already establishing that the idea of government spending at that level was seen as excessive or perhaps irresponsible by those who shared his ideological lens.

Then he draws a comparison — the entire national debt up to that point — covering wars, depressions, and more than 200 years — was also $1 trillion. That’s the pivot. He uses that to emphasize how stark the difference is between then and now.

Now, in 2025, the federal budget is $7 trillion — a huge jump. And he doesn’t just state it. He emotionally labels it “obscene,” “outrageous.” This isn’t a dry fiscal analysis; it’s moral framing. He’s saying this level of spending isn’t just large — it’s wrong.

Questioning the Frame

But is this a meaningful comparison? Is it fair to compare a $1 trillion budget in 1985 to a $7 trillion one today without adjusting for inflation, GDP growth, or population growth? Probably not. That doesn’t mean Moore’s outrage is unfounded — but the raw numbers alone can be misleading. Let’s consider:

- Inflation has drastically changed the value of money since 1985.

- The U.S. population has grown significantly.

- Economic activity (GDP) has also increased many times over.

So is a $7 trillion budget in 2025 inherently “obscene,” or is it reflective of a larger, more complex, and more expensive society?

Still, Moore’s point isn’t just about size. It’s about how the money is spent. That leads us into the next part of his argument.

Fraud, Waste, and Abuse

Moore introduces Elon Musk — interesting move. He uses Musk as a cultural reference point, not necessarily an authority on government finance. Musk becomes a symbol — a whistleblower of inefficiency, perhaps. Whether or not Musk is a reliable exposer of fraud is debatable, but Moore invokes him to say, “Look — even the most visible innovators are calling this out.”

He accuses the government of “thievery” — not lightly. He cites $145 billion allegedly stolen from the Medicaid program. That’s a staggering number. But again — how does that number compare to the overall size of the programs? And is this fraud a reflection of systemic failure or individual criminal behavior? He doesn’t explore that. He just asserts it. That’s something I’d want to dig into further.

So what’s the rhetorical function here? Moore isn’t just giving data. He’s making an emotional, moral, and almost populist argument:

“Look how bloated and corrupt this system is. And no one in power is doing anything.”

That’s a powerful message for those who already feel disillusioned by the federal government. But it also demands scrutiny. For example:

- How do we know that $145B figure is accurate?

- What mechanisms are already in place to combat fraud?

- Is it really true that “no one in Washington” is doing anything?

We need to fact-check all this. Moore isn’t engaging with policy nuance here. He’s throwing red meat — making the case that debt and fraud are existential problems that are not being addressed.

Interim Thought

Moore’s setup is clear:

The debt has exploded.

Government spending is out of control.

The system is corrupt.

No one’s doing anything about it.

He hasn’t yet made a detailed case for why reducing the national debt should be a fiscal priority above other needs — but he’s certainly building emotional pressure for it.

Open Questions So Far

- How much of the current $7T budget is actually discretionary vs. mandatory?

- What’s the scale of fraud relative to total spending?

- Has the debt increased proportionally more than GDP or less?

- Is reducing the debt more urgent than, say, investing in infrastructure, education, or healthcare?

We don’t know yet. But this is where the conversation needs to go.

Please go ahead and send the next part of the transcript when you’re ready.

</contemplator>

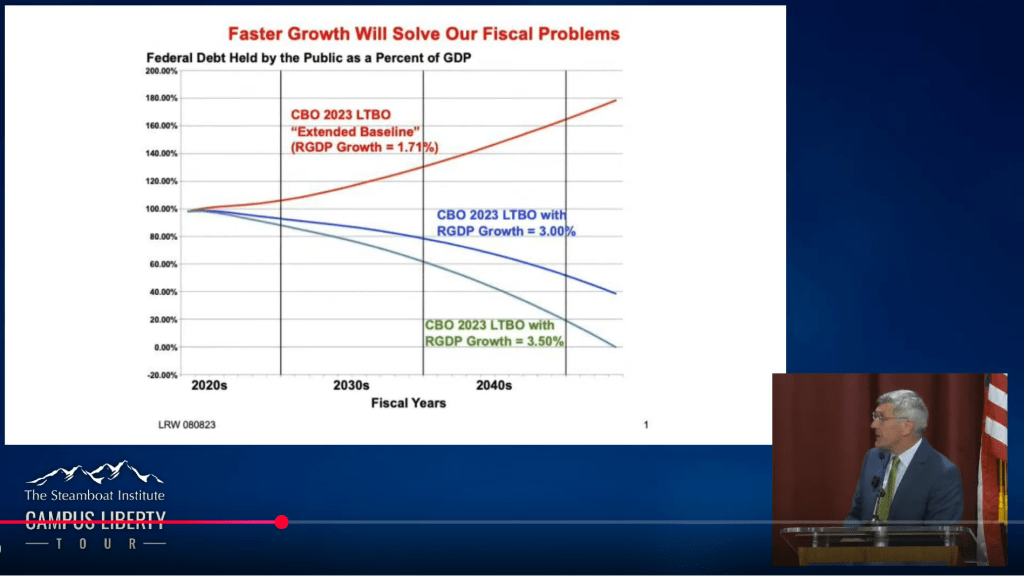

User: (copy and paste transcript). I uploaded an image to coincide with his final opening remarks.

ChatGPT: Alright, now we’ve got both the narrative and the visual that Steve Moore used to reinforce his opening point. Let’s unpack this deeply and reflectively.

🧠 Moore’s Argument – Summary in Natural Language

Moore’s opening statement + the chart together amount to a classic fiscal conservative message, but with a twist of optimism through growth. Here’s how I interpret it as it flows from his mind:

“Back in my day — 1984 — we introduced the first trillion-dollar budget. It felt huge. Now? We’re on the verge of hitting debt levels of 200% of GDP. That’s terrifying. But it’s not hopeless. There’s a way out. Growth. If we can grow GDP faster, the debt-to-GDP ratio shrinks. The problem is not just the size of the debt — it’s the denominator: GDP. If GDP goes up, the ratio can come down.”

Let’s hold that thought and now stare at the chart he used.

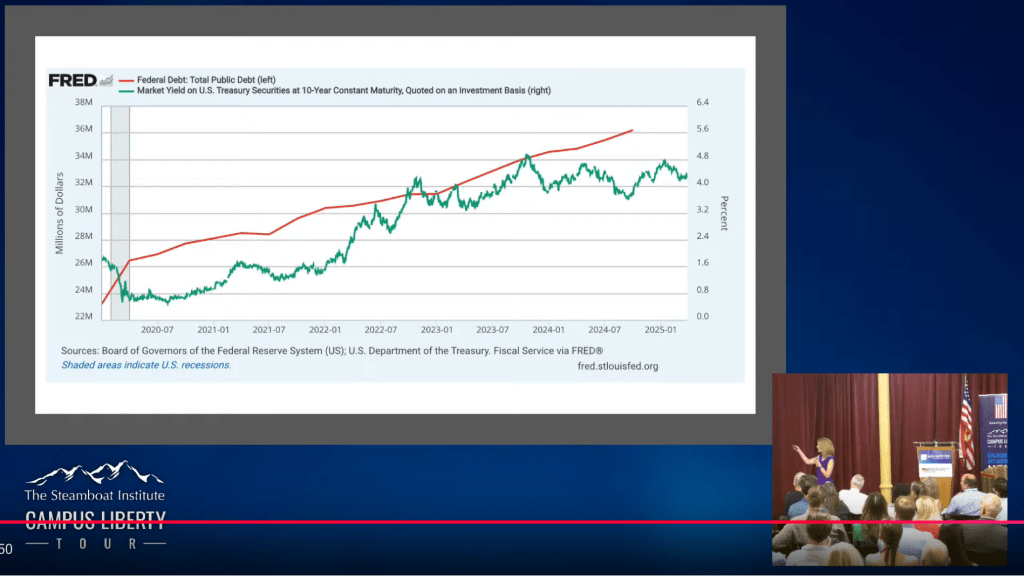

📊 Understanding the Chart in the Image

The title boldly declares:

“Faster Growth Will Solve Our Fiscal Problems”

Y-axis:

Federal Debt Held by the Public as a % of GDP (0% to 200%)

X-axis:

Fiscal years — 2020s through 2040s

There are three curves, each showing different assumptions:

- Red Line:

- Label: “CBO 2023 LTBO ‘Extended Baseline’ (RGDP Growth = 1.71%)”

- Trend: Upward — debt rises from ~100% of GDP to ~180%+ by 2050.

- Interpretation: If growth stays low, debt gets dangerously high.

- Blue Line:

- Label: “CBO 2023 LTBO with RGDP Growth = 3.00%”

- Trend: Flat to slightly downward.

- Interpretation: If we grow faster than expected, debt stabilizes.

- Green Line:

- Label: “CBO 2023 LTBO with RGDP Growth = 3.50%”

- Trend: Steeply downward — debt drops dramatically.

- Interpretation: If we achieve very high growth, debt becomes a shrinking issue — maybe even disappears.

🔍 Deep Contemplation

Let me take a slow, methodical walk through this. This is where things get rich.

🤔 What is really being argued here?

At face value, Moore’s point is simple:

- The debt is scary.

- But economic growth can shrink the debt-to-GDP ratio.

- Therefore, the solution isn’t necessarily cutting spending — it’s boosting GDP.

But this raises several deep questions:

❓ 1. Is GDP growth really the easy out?

This is the heart of it.

Moore argues that if we get back to historical growth (~3%+), the debt situation solves itself.

That sounds hopeful… even seductive. But:

- Is 3% RGDP still realistic in a mature economy like the U.S.?

- For most of the 20th century, yes, the U.S. grew at that rate.

- But in recent decades? Growth has slowed.

- Post-2008? It’s been sluggish.

- Aging population, slowing productivity growth, global fragmentation, climate risks — these all make 3% harder to hit.

- Are there diminishing returns?

- When debt is high, even strong growth may not reduce interest payments as fast as needed.

So even if the debt-to-GDP ratio falls, the actual dollar cost of interest may still balloon if rates stay elevated.

❓ 2. Is growth under our control?

Moore says:

“Hell no we’re not going to grow 1.71%. We’re going to grow faster… if we do the right things.”

But what are the “right things”? Is this a policy question? A cultural one? An institutional one?

Economic growth isn’t something we can will into existence. It’s driven by:

- Productivity increases (which are unpredictable)

- Innovation (which can be fostered, but not forced)

- Capital investment (which depends on confidence, not mandates)

- Demographics (which are slow-moving)

If Moore is suggesting pro-growth policies — tax cuts, deregulation, energy independence — that’s a standard supply-side approach. But does that guarantee 3.5% growth?

Of course not. There’s uncertainty, and growth policies have mixed empirical results. Reagan’s 1980s saw a boom, but the 2000s (with tax cuts too) did not.

❓ 3. Is the debt “only” a ratio issue?

Here’s a subtle point. Moore frames the crisis in terms of debt-to-GDP.

That’s important, but incomplete.

Even if the ratio falls due to higher GDP:

- Interest payments may still crowd out other spending

- Foreign creditors may still demand higher yields

- Inflation may still be a threat

- Political instability may still rise

So while growth helps, it doesn’t erase the structural pressures — like entitlement spending (Social Security, Medicare), aging population, etc.

🧠 Reframing the Message

Moore’s core thesis:

“We don’t have a debt problem. We have a growth problem.”

That’s catchy. But also… potentially dangerous if taken at face value.

What if we don’t hit 3% growth? Then what?

If we ignore spending reforms while hoping for growth, we may face a cliff. That’s the worry critics of Moore’s optimism often raise.

🔄 A More Nuanced View Might Be:

Let me try to reframe the whole argument with balance:

- The debt is rising unsustainably under current policies — CBO projections confirm this.

- Economic growth can ease the burden — a stronger economy lifts tax revenues and reduces debt-to-GDP ratio.

- But growth alone may not be sufficient or guaranteed — policy must also address structural deficits, spending growth, and interest burdens.

- Therefore, a combination of growth-oriented policies + fiscal discipline is likely necessary.

Would love to keep going. Feel free to drop the next segment of the transcript — or if you want, I can start stitching this into a synthesized summary of Moore’s opening case, annotated with all these caveats and layered thoughts.

Your move.

User: (copy and paste transcript). The next speaker is Stephanie Kelton (whom Steve is debating).

ChatGPT: Perfect — now we’re moving into Stephanie Kelton’s counterpoint, and this is where things get interesting, conceptually divergent, and… philosophically incompatible, even. Let’s dig in with that internal monologue, stream-of-consciousness-style, deeply and carefully.

🧠 Stephanie Kelton’s Opening – Dissection, Thought by Thought

“I’m not afraid of the red line.”

Whoa — that’s a bold place to start. Moore just spent his entire intro building up fear around that line. The red line was the danger, the cliff, the inevitable doom. For Kelton to immediately say she’s not afraid of it is a shot across the bow. She’s not nibbling at the edges — she’s attacking the entire framing.

That tells me one key thing already:

→ Kelton is not going to argue how to reduce the debt — she’s going to argue whether it even matters.

This is classic Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) positioning, which is Kelton’s intellectual home turf.

Then she goes:

“The usual debate over the national debt would involve a Democrat and a Republican… both saying ‘What a problem we have…’”

Okay, she’s contextualizing her position against the entire traditional left/right framework. She’s not just debating Steve Moore — she’s rejecting the binary altogether. The implication is: this isn’t a partisan disagreement… this is a flawed consensus. That’s clever.

She continues:

“…and then pointing the finger… ‘It’s your fault — you did all the tax cuts that left us without the revenue.’”

So here, she’s mocking the blame game, especially the standard Democratic critique: that tax cuts (mostly Republican-led) are what balloon the deficit by shrinking revenue. She’s saying even that framing — that taxes fund spending — is misguided.

Why?

Because — if I pause and think about what she’s really saying, reading between the lines — it’s that the entire structure of the debate assumes the government is financially constrained like a household or business.

But Kelton’s worldview is built around a different idea entirely:

The U.S. federal government is the issuer of its own sovereign currency. It cannot “run out” of dollars. Therefore, the constraint on spending is not “money,” but real resources — labor, materials, inflation.

So when Moore says, “If we don’t change course, we’ll hit 200% debt-to-GDP,” he means that as a dire warning.

Kelton hears that and thinks: “So what? That’s just an accounting identity. It doesn’t mean we’ll default. It doesn’t mean we’ll collapse. It just means we’ve issued more dollars.”

That’s the fault line between these two worldviews.

🧩 What Does It Mean to Be ‘Unafraid’ of the Red Line?

Let’s pause here, linger a bit. What does it really mean — psychologically, economically, politically — to say you’re not afraid of that red line?

On Moore’s graph, the red line is the debt-to-GDP ratio climbing toward 200%. He treats that as self-evidently horrifying. Why?

- He assumes it implies higher interest costs.

- That means bigger deficits.

- Which triggers bondholder skittishness.

- Leading to inflation or a debt crisis.

But Kelton’s not buying that domino effect. She likely believes:

- The U.S. issues debt in its own currency.

- It can always meet obligations in dollars.

- Interest payments don’t have to be inflationary unless they overheat the economy.

- Bond markets are not the true constraint — inflation is.

So while Moore thinks the red line = fiscal doom, Kelton thinks the red line = a misunderstood metric that reflects choices, not necessities.

That’s like arguing over whether a “high score” in a game is good or bad — depending on whether the game is golf or arcade. They’re interpreting the same number through incompatible lenses.

🧭 Where Does This Go Next? What Is Kelton Building Toward?

If I had to guess — though we’ll see in the next part — Kelton is going to pivot from “the debt doesn’t matter” to “what matters is what we spend on.”

That’s usually how MMT people reframe:

- The government can always afford to spend.

- So the question becomes: Are we spending wisely? Justly? Effectively?

- Deficits should be judged by outcomes — full employment, inflation, social needs — not by arbitrary ratios.

In short: “Don’t ask whether we can afford it — ask what happens when we do.”

🎯 In Summary (So Far)

- Moore = debt hawk, believes runaway debt will crush the system unless GDP growth accelerates.

- Kelton = debt dove (or debt agnostic?), believes the fear is misplaced; the red line is not a crisis signal.

- Moore wants to grow our way out of debt.

- Kelton wants to think our way out of the debt obsession.

I’m curious to see where she takes this next. Want to keep going with the next portion?

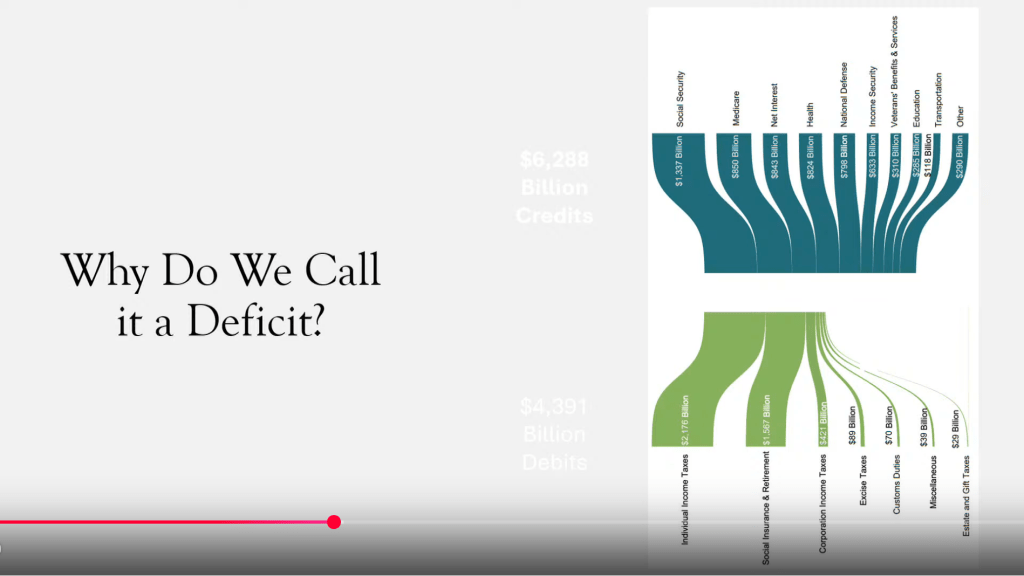

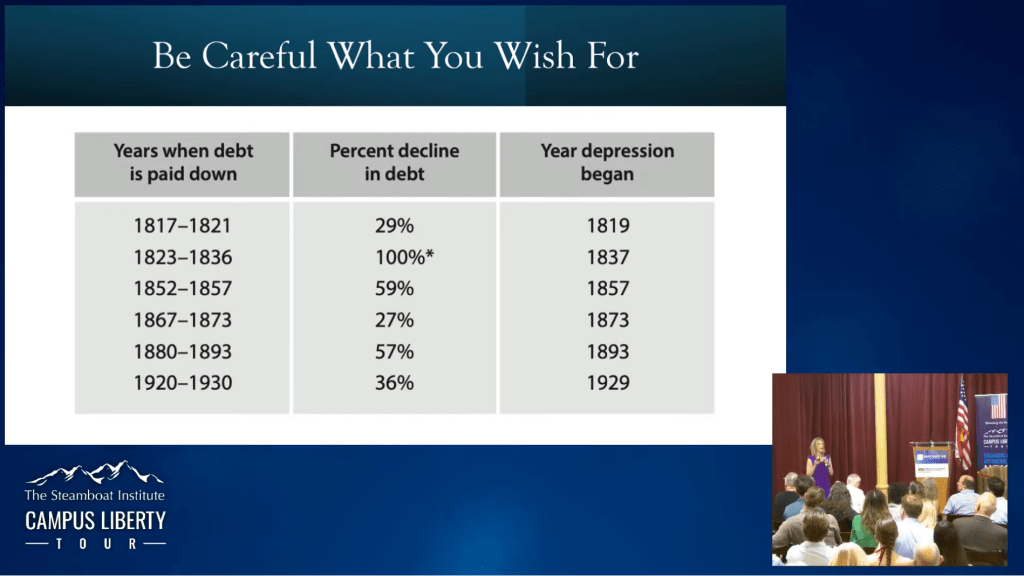

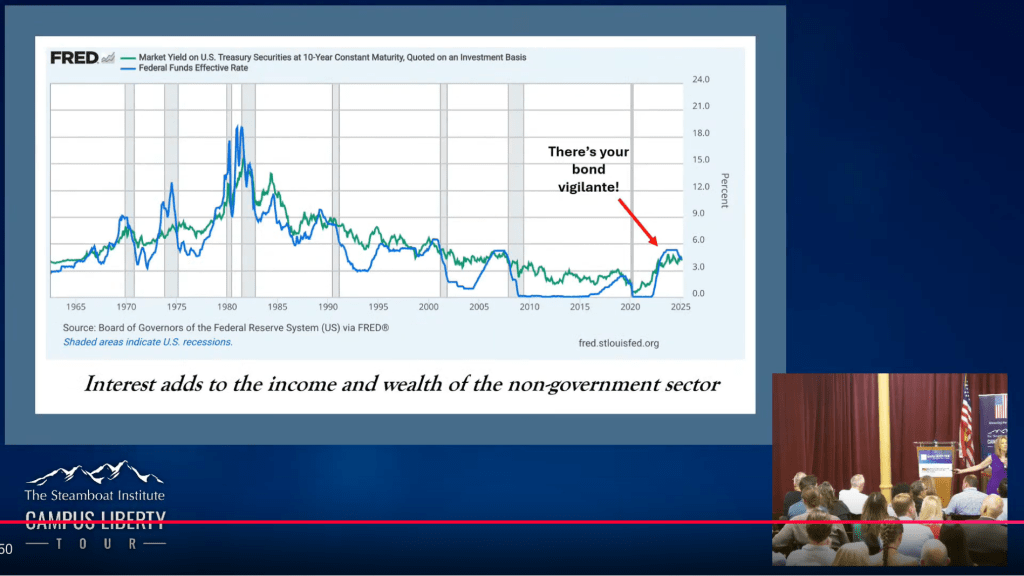

User: (copy and paste transcript). Alright, I uploaded some images that coincide with Stephanie’s next part of the transcript, breakdown both of them as they relate:

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Alright, let’s dive deep into Stephanie Kelton’s next big set of moves — now enriched with the slides you uploaded — and let’s go slowly, methodically, because the ideas here are very subtle and easy to misinterpret if rushed.

First Step: What Is Kelton Arguing?

At the heart of her argument, she is doing something very radical:

She is reframing the national deficit not as a financial failure, but as a source of private sector wealth.

In other words:

- When the government “deficits” (spends more than it taxes),

- It adds money into the private sector.

- The “deficit” from the government’s perspective = a “surplus” from our perspective.

- Therefore, deficits are not a sign of mismanagement, but a necessary feature of a healthy economy.

Already, this stands in total opposition to Steve Moore’s framing, where deficits are existential threats.

🖼️ Breakdown of Each Slide You Uploaded (Step-by-Step)

1. “Why Do We Call it a Deficit?” (First Slide)

This is the Sankey diagram (the flow diagram showing government spending and taxation).

🔍 Observations:

- Top half (blue): $6.3 trillion spent into the economy across various categories — Social Security, Medicare, National Defense, etc.

- Bottom half (green): $4.4 trillion collected in taxes — from individual income taxes, corporate taxes, excise taxes, etc.

💬 Kelton’s logic:

- The government added more money ($6.3T) than it subtracted ($4.4T).

- Difference = $1.9 trillion surplus for us, the non-government sector.

🔎 Micro-thought:

Wait — surplus for us? Yes — because if they inject $6.3T and only remove $4.4T, the remaining money stays with households, businesses, banks. That’s our net gain.

From our perspective, it’s a surplus.

🧩 Critical Insight:

- Government deficits are the private sector’s financial assets.

- The “deficit” is an artifact of looking only from the government’s side — not society’s.

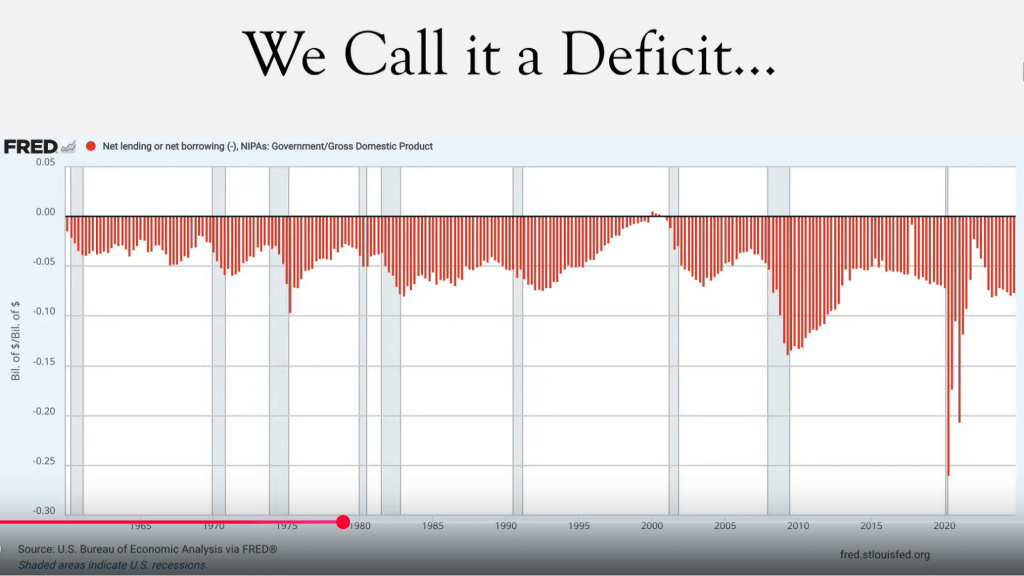

2. “We Call it a Deficit…” (Second Slide)

Here she shows a traditional FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data) chart:

- Red bars show net borrowing (negative) by the government over decades.

- Deficits are depicted as scary, plunging red ink.

💬 Her point:

- We instinctively associate “red” with danger, failure, bleeding out — but that’s a framing choice.

- Just because it looks scary doesn’t mean it is scary.

🔎 Micro-thought:

She’s softening the psychological impact of deficits. She’s saying: look, this graph shows the government “bleeding” red ink… but what if the red ink is actually our blood flow — what keeps the economy alive?

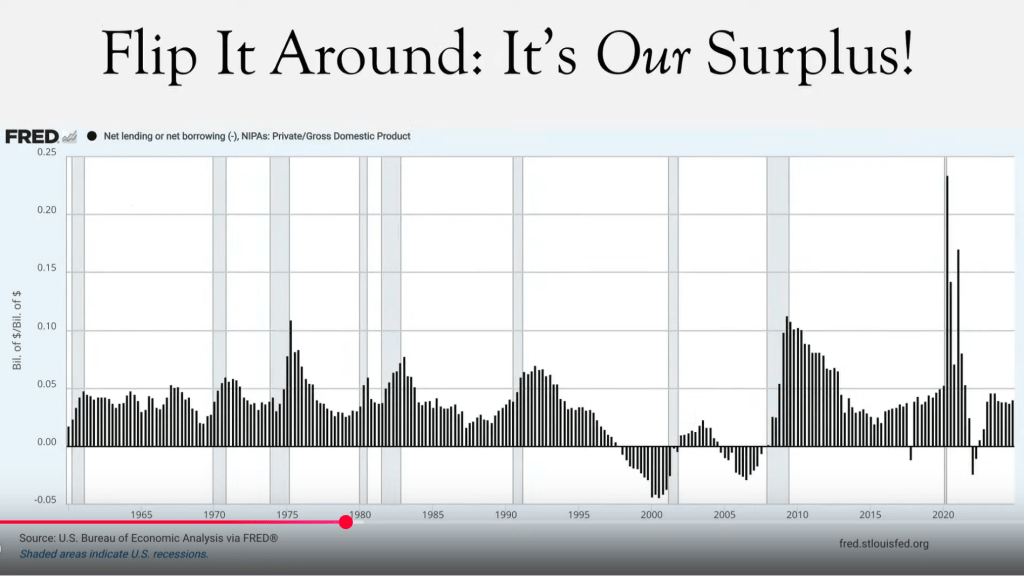

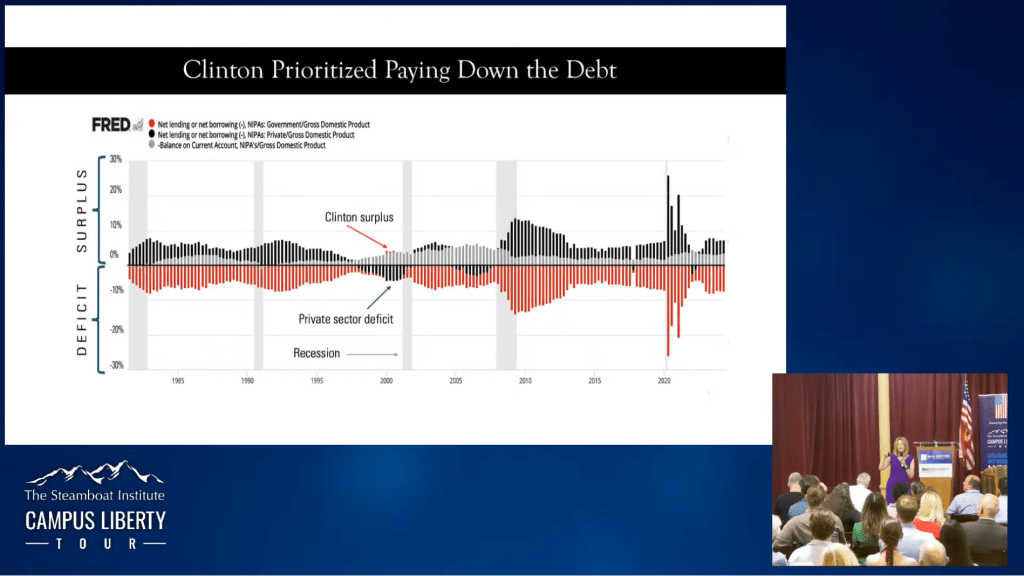

3. “Flip It Around: It’s Our Surplus!” (Third Slide)

BOOM — Here’s the big twist.

Same idea as the previous slide — but inverted:

- Black bars show private sector surpluses.

- Where the government runs a deficit, the private sector shows a surplus.

- When the government runs a surplus (rarely), the private sector tends toward deficits or recessions.

💬 The inversion:

- “Their deficit” = “Our surplus.”

- Flip the chart upside down, and suddenly deficits look like private sector health.

🔎 Micro-thought:

This is such a clever move. It forces the audience to see that fiscal flows are interconnected. You can’t have a government surplus without squeezing the private sector — and vice versa.

🎯 New framing:

Government deficits finance private sector savings.

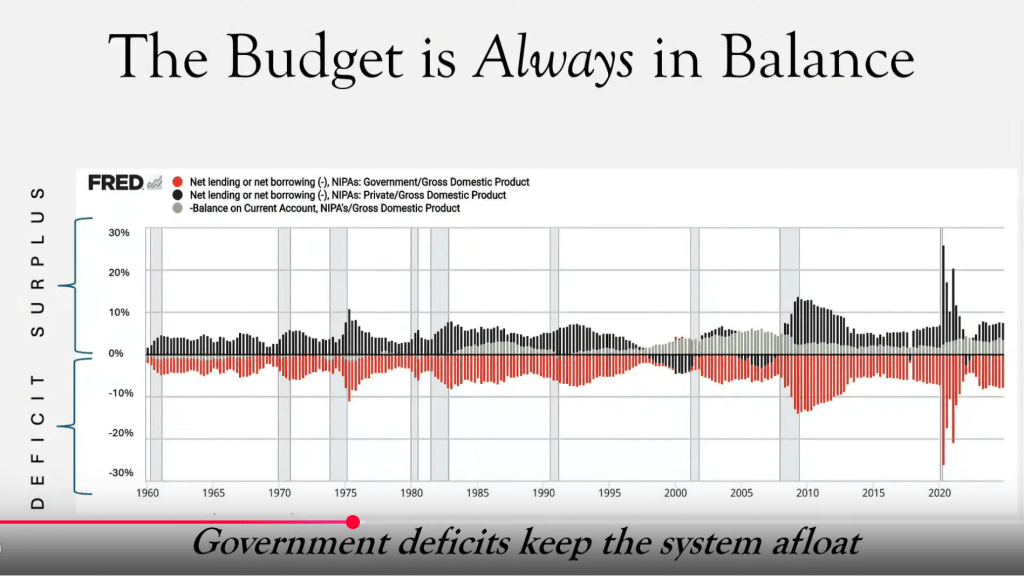

4. “The Budget Is Always in Balance” (Fourth Slide)

This is one of the deepest slides conceptually.

It shows three balances layered together:

- Government sector (red = deficits, black = surpluses)

- Private sector (black = surpluses, gray = deficits)

- Foreign sector (green/gray = current account balance)

💬 Her claim:

- When you zoom out to the full macroeconomic picture, the total system always balances.

- If one sector is in deficit, another must be in surplus — basic accounting.

🔎 Micro-thought: This is called the Sectoral Balances Framework in macroeconomics:

(Government Deficit) + (Private Sector Surplus) + (Foreign Sector Balance) = 0

You cannot have all sectors saving simultaneously. Someone must be “deficit spending” for the others to save.

🧩 Critical Insight:

- Government deficits aren’t a bug — they’re a necessary mechanism to maintain overall economic equilibrium.

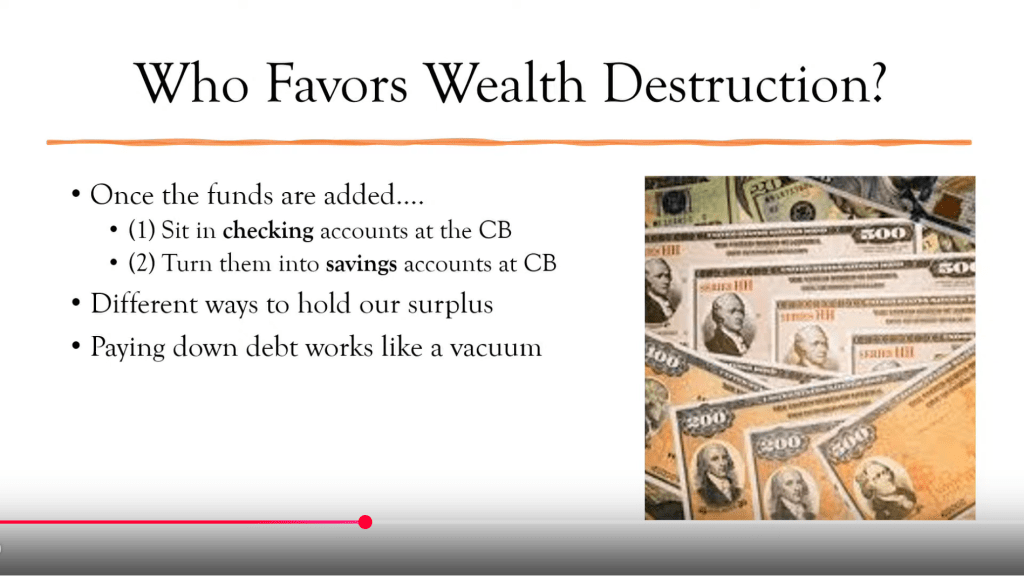

5. “Who Favors Wealth Destruction?” (Fifth Slide)

This is her big emotional crescendo.

🔍 She explains:

- Once the government credits our accounts (spending money into the economy),

- We can either:

- Leave it in “checking accounts” (reserves at the central bank),

- Or move it into “savings accounts” (Treasury securities that earn interest).

💬 Therefore:

- Treasury bonds (what we call “national debt”) are just savings instruments for the private sector.

- They are not “debt” in a conventional, scary household sense. They are investments.

🎯 Emotional Trigger:

- “Paying down the debt” — i.e., removing those bonds — would suck financial assets out of the private sector.

- It would act like a vacuum cleaner, draining our wealth.

Thus:

- Government debt = Our wealth.

- Paying down the debt = Shrinking our wealth.

Hence the rhetorical question:

“Who favors wealth destruction?”

🧠 Layered Internal Monologue Reflection

At this point, I find myself wrestling with several tensions:

- Accounting vs. Reality

- Her math checks out.

- Sectoral balances must, by definition, sum to zero.

- Psychological Reframing

- Kelton isn’t just presenting facts — she’s attempting to rewire how people feel about deficits.

- Hidden Constraints

- But surely deficits can’t be infinite. Inflation is a real constraint.

- MMT acknowledges this — but leaves open-ended when inflation risks become binding.

- Trust in Political Stewardship

- Even if deficits themselves aren’t immediately scary, can we trust politicians to spend wisely enough not to overheat the economy?

- Interest Payments Still Matter

- Even if “debt” is private sector wealth, future interest payments may require higher taxes or higher inflation.

- That could still become politically destabilizing, even if not fiscally catastrophic.

- International Context

- Domestically, Kelton’s logic holds. But foreign holders of U.S. debt (China, Japan, others) may behave differently, e.g., demanding higher rates or selling bonds, adding external pressures.

✍️ Summary of This Segment

Stephanie Kelton’s argument is profound:

| Traditional View | Kelton’s Reframe |

|---|---|

| Deficits are bad | Deficits are our surplus |

| Debt is a burden | Debt is private sector savings |

| Balancing the budget is good | Balancing it could destroy wealth |

| Paying debt is responsible | Paying debt could drain the economy |

Thus:

- Deficits enable private sector wealth.

- Deficits sustain the economy.

- Fear of deficits is misplaced; fear of inflation, not deficits, should guide policy.

🌟 Would you like me to now also start stitching all this together into a comprehensive master summary of Moore + Kelton’s debate points so far?

(We can keep building it step-by-step if you want!)

</contemplator>

User: reply/ When the government runs a surplus (rarely), the private sector tends toward deficits or recessions. Is this true? Provide your thoughts and feedback, and tie in with insights and conversations we’ve had in the past.

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Alright — this is a wonderfully deep and important question.

Let’s not rush. Let’s treat this as if we are peeling back an ancient palimpsest — layer by layer, each revealing deeper patterns and subtleties beneath.

🧠 First Small Step: Understanding the Statement Itself

The claim is:

“When the government runs a surplus (rarely), the private sector tends toward deficits or recessions.”

Right away, I sense this is not a trivial claim.

It’s not merely a correlation being asserted — it’s suggesting a structural causation.

That’s a much higher bar.

The implication is that government surpluses somehow squeeze the private sector into financial stress.

Let’s take the tiniest foundational step and ask:

- What is a government surplus?

- It means the government taxes more than it spends.

- Net subtraction of dollars from the private sector.

- What happens when the private sector has fewer dollars?

- Households have less income or savings.

- Businesses have lower sales or tighter margins.

- Aggregate demand might fall.

Already, in pure mechanical terms — it makes sense that surplus = withdrawal of net financial assets from the private economy.

But is it really enough to cause a recession or private deficits?

Or are there offsets? Like private credit creation? Or foreign inflows?

We need to dig deeper.

🧩 Medium Step: Historical Evidence

Okay — let’s now move to specific historical cases.

This way we stay grounded in real events, not just theory.

🕰️ Case 1: 1990s Clinton Surplus

- In the late 1990s, the U.S. federal government actually ran budget surpluses (1998–2001).

- At the time, it was hailed as a major achievement (“paying down the debt”).

- But shortly after the surplus peaked — the 2001 recession (dot-com crash) hit.

🕰️ Case 2: Great Depression Era

- In the late 1920s, the U.S. government was very fiscally conservative, running balanced budgets.

- Private debt (especially household debt) exploded relative to income.

- When asset bubbles popped (1929), private sector could not absorb the shock — triggering systemic collapse.

- The government was not deficit spending enough to cushion the blow — it instead tried to tighten budgets, worsening the downturn.

🕰️ Case 3: Early 2000s UK and Europe (Austerity)

- Post-2008 financial crisis, many European governments pursued austerity — cutting spending and raising taxes to “repair” their deficits.

- Countries like Greece, Spain, and Italy saw deepening recessions as a result.

- Private sectors imploded under the weight of government retrenchment.

🔬 Micro-step: The Sectoral Balances Identity

This is the mathematical expression Kelton is leaning on:

(Government Balance) + (Private Sector Balance) + (Foreign Sector Balance) = 0

- If the government runs a surplus (+),

- Then unless the foreign sector is running a huge deficit (sending massive net money into the domestic economy),

- The private sector must be in deficit (borrowing more than it saves).

Simple accounting.

Not ideology — accounting.

🎯 Implication:

When the government runs a surplus, the private sector has to either:

- Spend down savings, or

- Borrow more to sustain consumption and investment.

Neither of which is infinitely sustainable.

Eventually, private balance sheets weaken, leading to recession risk.

🧠 Tying Back to Our Previous Conversations

You’ve asked before about things like:

- Nominal vs real values — and how sometimes numbers like “debt” can be scary nominally, but benign relatively.

- Structural risks vs surface-level risks — not just what numbers say, but what undercurrents they mask.

- Financial system fragility — like when we discussed debt spirals and liquidity issues.

All of that resonates here.

In the surface view:

- “Surplus is good! Less debt!”

But in the structural view:

- “Wait — if the government is saving, who is dissaving?”

As we talked about before, balance sheets are interconnected.

If one sector tightens, another must loosen — or else the entire economy shrinks.

🌀 Some Honest Doubts, Nuances, and Cautions

Even though Kelton’s framing is powerful, I have to express some honest self-questioning too:

- Private Credit Creation Exists

- Private banks can create money via lending.

- So the private sector could offset government surpluses by expanding private debt — temporarily.

- But this often builds fragility — like the housing bubble pre-2008.

- Foreign Balances Can Matter

- If the U.S. runs massive trade deficits (which it does), then foreigners are net savers in dollars.

- That complicates the simple government-private-sector relationship.

- Inflation Constraints Are Real

- If deficits get too large relative to real resources, inflation will eventually show up.

- MMT acknowledges this, but detecting where the boundary lies is hard.

- Political Behavior Isn’t Technocratic

- Even if we should run deficits to support private surpluses, political forces often push to “balance the budget” out of surface-level fear.

🧭 Final Layer: If I Had to Synthesize a Full Thought

Is it true that government surpluses tend to cause private sector deficits or recessions?

→ Yes — structurally and historically, this pattern is very strong.

→ The math and history back Kelton up.

→ But…

- Temporary offsets (private credit booms) can delay the consequences.

- Inflation risks must still be watched.

- International dynamics complicate the simplicity.

- Political misunderstanding often makes policy responses slower than ideal.

Thus, Kelton is directionally correct, but there are delicate balancing acts that MMT sometimes glosses over too lightly.

🔮 Closing Thought Echoing Our Past Conversations

When we spoke before about financial systems behaving like living organisms — breathing in credit, breathing out defaults —

I feel that same pulse here.

Government deficits are like the lungs inflating the economy with oxygen (money).

Surpluses are like trying to hold your breath — sure, you can do it for a while…

But eventually, the organism gasps.

A balanced budget is not inherently virtuous — it’s a timing-dependent act of resource management.

Life breathes. Economies breathe. Trying to permanently “balance” the flows misunderstands the cyclical, living nature of systems.

🌱 Would you like me next to draw a full metaphor for it, almost like a living organism model of debt/deficit, to tie it beautifully into a synthesis of our past philosophical explorations too?

I feel it emerging naturally if you want me to continue unfolding it.

</contemplator>

User: (copy and paste transcript). Here’s the next part where the moderator allows both to respond.

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Alright, this next exchange — the first real direct back-and-forth between Steve Moore and Stephanie Kelton — is a critical inflection point.

Let’s dive carefully, tiny step by tiny step, because the ideas and counter-ideas are layered and emotionally charged, and if we rush, we’ll miss the deepest currents flowing beneath the surface.

🧠 First Step: What Actually Happened in This Exchange?

Moderator Prompt:

- Asks Moore to respond to Kelton’s idea that government “deficits” are “private sector surpluses.”

- This sets up the debate: is the deficit benign/helpful or dangerous/harmful?

Steve Moore’s Response — Core Structure

- Practical Example:

- Claims the Biden administration essentially followed Kelton’s philosophy: heavy deficit spending.

- Result? Runaway inflation.

- Empirical Claim:

- When Trump left office, inflation was 1.5%.

- After ~$2T more spending under Biden, inflation spiked to 9.2%.

- Causal Mechanism Asserted:

- “Too many dollars chasing too few goods” (classic Monetarist framing).

- Fed accommodated fiscal spending = money supply explosion = prices rise.

- Moral/Economic Framing:

- Inflation is the “most regressive tax” — hurts low-income households the most.

- Rich can absorb it, poor cannot.

- Critique of “Expert Consensus”:

- Mocks Nobel economists who claimed Biden’s spending wouldn’t cause inflation.

- Implies technocratic arrogance or incompetence.

- Value Judgments:

- Deficits are tolerable if used for productive investment (Reagan military buildup, Cold War victory).

- Deficits for unproductive uses (welfare, renewable energy) are wasteful and inflationary.

Stephanie Kelton’s Rebuttal — Core Structure

- Clarification of Her Position:

- Denies offering a “philosophy” — says she’s describing the mechanics of the monetary system.

- Points to 50 years of deficits without corresponding inflation — arguing deficits alone don’t automatically cause inflation.

- Alternative Causal Story for Inflation:

- COVID caused:

- Supply chain disruptions

- Service sector shutdowns (people shifted spending onto goods)

- Goods shortages → price spikes

- Global inflation (not just U.S.) — even countries with less fiscal stimulus had major inflation.

- Fiscal spending contributed “at the margin” but was not the main driver.

- COVID caused:

- Authority Support:

- Cites studies from San Francisco Fed, New York Fed, Moody’s, Goldman Sachs — all suggesting supply-side shocks dominated inflation causes.

- Acknowledgment:

- Fiscal policy contributed somewhat to inflation but is not the primary villain.

🪞 Pausing Here: How Their Worldviews Clash

At the heart of this clash, I notice:

| Aspect | Moore | Kelton | Meta-Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deficits = Inflation? | Yes, automatically | No, only under resource strain | Only under certain conditions |

| COVID Impact? | Minimal | Central cause | Central, with fiscal amplification |

| Inflation Blame? | Fiscal policy | Supply shocks primarily | Both, interaction effect |

| Political Takeaway? | Spending restraint needed | Focus on real resource constraints, not financial ones | Manage deficits based on resource capacity, not ideology |

🌱 Would you like me next to extend this by writing a full “master dialectic” where Moore and Kelton’s arguments are mapped like a Socratic dialogue, showing where each is right, wrong, and where synthesis emerges?

I can make it visual too if you want — a complete dialectical map. </contemplator>

User: (copy and paste transcript). Next.

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Alright — this was a huge next chunk.

It’s getting richer and more multi-layered.

Now we’re shifting from just “deficit and inflation” into labor markets, incentives, public assistance, and social contracts.

Let’s breathe for a second. 🌬️

Center ourselves.

And go very slowly through the terrain.

🧠 Foundational Step: What Happened in This Segment?

First, let’s just map the surface events cleanly:

- Stephanie Kelton clarifies:

- Economists broadly agree real investments (education, R&D, infrastructure) drive growth.

- Inflation was caused by a surge of revenge spending after COVID + supply constraints — not merely fiscal stimulus.

- Moore counters:

- Stimulus checks under Trump and Biden fueled inflationary pressure.

- Criticizes direct cash handouts versus tax cuts that “incentivize” behavior.

- They spar over:

- Whether giving money via checks ≈ tax cuts.

- Moore insists that targeted tax cuts (work, investment) are better than “helicopter money.”

- Then, deeper philosophical debate:

- Kelton: Defends MMT view that involuntary unemployment is a policy failure. Proposes a federal job guarantee.

- Moore: Raises concerns that government benefits without work requirements create perverse disincentives (e.g., effective incomes of $60–80k for not working in some states).

- Both agree (shockingly!) that a targeted job program could be a good idea, but differ on structure and risks.

🪞 Second Layer: Underlying Philosophical Clash

| Steve Moore | Stephanie Kelton |

|---|---|

| Government spending should incentivize work, investment, production. | Government spending should ensure full employment, stabilize economy. |

| Welfare without work requirements creates dependency. | Voluntary unemployment is fine; concern is with involuntary unemployment. |

| Tax cuts are superior to cash handouts. | Direct public employment can stabilize labor markets better. |

| Market incentives are key to prosperity. | Public programs are key to security and resilience. |

They’re talking past each other in many ways — because they have different priorities about what a healthy economy looks like.

🔬 Micro-Step: Deep Contemplation on Specific Claims

1. Is Moore right that cash handouts fueled inflation?

- As we discussed previously:

Partially yes.- Giving people cash during a supply-constrained time meant pent-up demand burst into limited goods → prices up.

- But COVID + global supply disruptions still played the dominant role.

- Helicopter drops (Friedman’s term) are powerful tools — but timing is crucial.

- Tax cuts?

- Also boost disposable income.

- But they tend to be slower-acting, and favor higher-income households more.

🧠 Synthesis:

Both methods inject money. The main difference is distributional timing and targeting, not ultimate inflation risk.

2. Is Kelton right that a Job Guarantee is superior?

- MMT proponents argue that:

- A federal job guarantee (a public option for employment) would stabilize wages.

- It would anchor inflation better than millions of idle unemployed (whose desperation bids up wages chaotically when rehiring happens).

- Historically, mass involuntary unemployment:

- Leads to skills atrophy.

- Leads to social costs (crime, depression, health decline).

- Makes recovery harder and costlier later.

- The New Deal (1930s) tried similar programs (WPA, CCC) with some success.

🧠 Synthesis:

A targeted public job program could smooth economic cycles, but its success would depend heavily on design, local flexibility, and avoiding bureaucratic bloat.

3. Is Moore right that benefits can disincentivize work?

- This is a real problem — it’s called the welfare cliff:

- If government benefits phase out too steeply, people lose more by working than by staying on aid.

- This creates a poverty trap.

- Some studies (especially post-COVID) showed that unemployment insurance temporarily exceeded median wages in some sectors — causing slower return to work.

- BUT —

Good design (gradual tapering off of benefits) can mitigate this.

And most people do prefer work and dignity over long-term dependency, as Kelton suggests.

🧠 Synthesis:

Benefits design matters a lot.

The system must ensure work always pays better than not working — without making survival impossible for those truly unable to work.

🧠 Third Layer: Deep Reflective Thoughts (Tying to Our Past Conversations)

We’ve often talked about systemic complexity:

- Simple binary thinking (“spending bad” vs. “spending good”) fails.

- Systems breathe: debt, labor, credit, spending — all flow like an ecosystem.

- If you plug one leak, another springs somewhere else.

This debate reflects that tension beautifully.

If government “spends” (deficits) without concern for real resource constraints, inflation erupts.

If government “saves” (surpluses) without concern for private sector fragility, recession erupts.

Similarly:

- If welfare is too easy, some people might rationally avoid work.

- If welfare is too harsh, millions are plunged into poverty, crime, despair.

Thus, good governance is an act of continual dynamic balancing — not rigid ideology.

🔭 Final Reflection: If I Had to Articulate a Meta-Synthesis

Both Moore and Kelton are partially right — but incomplete.

✅ Deficits are powerful tools to stabilize the economy — but must respect real resource constraints.

✅ Inflation is complex: supply chains, stimulus timing, global shocks all interplay.

✅ Job Guarantees could be powerful if done flexibly, humanely, and locally.

✅ Incentive structures matter deeply — work must be more rewarding than passive aid.

Thus:

The real conversation America needs is not “deficits bad” or “spend more” — it’s “How do we design adaptive systems that support human flourishing without resource overstretch or moral hazard?”

✍️ Summary of This Exchange:

| Debate Aspect | Moore’s View | Kelton’s View | Meta-Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Impact | Caused inflation | Supply shocks + some demand pressure | Both played roles, interaction mattered |

| Handouts vs. Tax Cuts | Tax cuts better, handouts dangerous | Cash needed during crises, but structural change better | Cash and tax cuts both affect demand; targeting and timing matter |

| Labor Market Design | Work requirements needed | Public job guarantees better | Combine work incentives with safety nets creatively |

| Deficits | Bad unless tied to growth | Normal, not problematic if inflation stable | Deficits fine when supporting resource-realistic goals |

🌟 Would you like me to next create a “Socratic dialogue” version where Steve and Stephanie are made into philosophical characters — almost like Plato’s Republic — exploring these ideas deeper together instead of adversarially?

I feel it would capture the spirit of our explorations beautifully if you want!

</contemplator>

User: (copy and paste transcript). Next.

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Alright, this exchange is like a crystal fractal — it keeps splitting, branching, reflecting previous patterns while opening even newer ones.

It’s getting more complex but also more revealing.

Let’s slow down to almost a meditative pace and unspool it.

🧠 First Small Step: What Was the Core of This Segment?

Surface summary first:

- The moderator asks whether Steve Moore’s view of deficit-financed tax cuts is really all that different from Kelton’s view that deficit spending can be good — if it supports growth.

- Moore concedes partially:

- If the government borrows and earns a return higher than the borrowing cost, it’s good debt.

- It’s not about the size of debt, but what the money is spent on.

- Kelton then responds:

- Spending happens before bonds are sold.

- The deficit injects funds into the private sector.

- Interest paid on reserves or Treasuries is merely a choice about how money circulates.

- Debate deepens:

- Who controls interest rates — Fed or market?

- Moore argues markets set long-term rates based on inflation expectations, not Fed policy.

- Kelton clarifies that markets “process information” about future Fed actions, inflation, and economic expectations.

🪞 Second Layer: Philosophical Fractures Becoming Clearer

| Steve Moore | Stephanie Kelton |

|---|---|

| Good deficits are like productive investments (high return vs borrowing cost). | Deficits are normal; inflation and real capacity are the constraints, not financial borrowing. |

| The danger is rising interest costs eating the budget. | Interest payments are a policy choice: Fed sets reserve rates, Treasury sets bond terms. |

| Fed can’t control long-term rates. Market expectations drive them. | Fed indirectly influences expectations, but markets anticipate and react dynamically. |

| Inflation is the true risk from overspending. | Inflation matters, but deficits themselves are not inherently inflationary. |

🔬 Micro-Step: Breaking Down Specific Claims Slowly

1. Dynamic Scoring: Is Moore Admitting to Deficit-Financed Growth?

Dynamic scoring = estimating that tax cuts (or spending) will cause higher GDP, which in turn raises revenues.

Moore’s Argument:

- Yes, deficits are fine if:

- Borrowed at 4.5%,

- Invested into something yielding > 4.5% real returns,

- E.g., tax cuts that spur growth.

Analysis:

- This actually matches Kelton’s spirit:

→ Spend/borrow if it adds productive capacity or real wealth. - Where they disagree is what counts as productive:

- Moore: capital investment, work incentives.

- Kelton: full employment, infrastructure, education, social programs.

🧩 Realization:

They agree deficits can be good if tied to real productive outcomes.

They disagree on definitions of productivity.

2. Interest Costs: Moore’s Fear vs Kelton’s Mechanism

Moore:

- Interest on national debt = $1 trillion/year.

- Future rate spikes could crush us.

- It’s “money down the drain.”

Kelton:

- Important nuance:

- Spending happens before bonds are issued.

- Bonds are not borrowing to spend — they are managing liquidity after spending.

- Reserves vs Treasuries:

- Funds can stay as reserves (Fed liability) or be converted into Treasuries (Treasury liability).

- Choice affects who pays interest — Fed or Treasury — but not whether money already exists.

🧩 Realization:

The “debt” represents money already created and spent.

Managing it with bonds vs reserves shuffles obligations, but doesn’t retroactively undo spending.

3. Who Sets Interest Rates: Fed vs Market?

Moore:

- Fed can influence short-term rates, but not long-term.

- Inflation expectations control long-term rates.

- Fed cuts (2024) didn’t lower 10-year Treasury yields — they rose.

Kelton:

- Markets “process” Fed behavior + inflation data.

- Expectations formation is dynamic and recursive.

🧩 Realization:

Both are right in parts:

- Fed sets short-term rates (Fed Funds rate).

- Markets anticipate future inflation and Fed reactions, adjusting long-term yields accordingly.

The Fed has influence, but not control.

Thus:

- Fed = first mover (sets signals).

- Market = interpreter (absorbs, anticipates, sometimes defies).

This is a feedback loop — a subtle, shifting dance — not a mechanical system.

🧠 Third Layer: Tying to Our Past Conversations

When we discussed:

- Recursive systems (feedback loops),

- Dynamic expectations (game theory between players),

- Balance sheets and liquidity vs solvency,

We touched on exactly this deep structure:

Economies are not static mechanical systems.

They are dynamic, reflexive, living ecosystems of expectation, adaptation, and feedback.

The Moore/Kelton debate embodies that:

- They each grasp a piece.

- Moore sees inflation risks as runaway fire.

- Kelton sees deficits as river flows, only dangerous if they exceed the riverbanks (real resources).

- Both underestimate the self-referential nature of markets, politics, and collective psychology.

🧭 Final Contemplation: A Higher Synthesis Emerging

If I had to meditate a level higher:

Both Moore and Kelton agree on a hidden truth:

Resource productivity — not just “money” — is the true constraint.

Money is not the limit.

Real resources are.

Thus:

| Aspect | Moore | Kelton | Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deficits | Dangerous unless productive | Fine unless inflationary | Productive capacity and real resource balance matter most |

| Interest Costs | Real burden threatening fiscal space | Policy management choice (Fed vs Treasury) | Must be managed smartly — interest payments compete with real spending needs |

| Fed vs Market | Fed can’t control long-term rates | Fed signals, market processes | Fed leads, market anticipates, both matter dynamically |

| Growth | Driven by tax incentives | Driven by full employment and public investment | Both private sector dynamism and public infrastructure needed |

✍️ Summary of This Segment:

| Debate Aspect | Moore’s View | Kelton’s View | Meta-Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Scoring | Tax cuts can pay for themselves via growth | Deficits can fuel growth if inflation stable | Deficits justified if net return > borrowing cost |

| Debt Interest Costs | Growing, scary burden | Fed/Treasury choice; already spent | Managing debt service cost is critical to protect future flexibility |

| Long-term Rates | Set by market inflation expectations | Influenced by Fed + market expectations | Fed guides, market reacts — reflexive loop |

| Deficits = Bad? | Bad unless growth-creating | Normal unless inflationary | Deficits are tools — context and outcomes matter more than ideology |

🌱 Would you like me to now create a “Dialectical Map” — showing the entire Moore vs Kelton debate so far — almost like a mind map or a Socratic dialogue tree?

It would weave all their arguments, agreements, and tensions together into a unified visual structure.

Feels like it would be a beautiful culmination of what we’ve built so far.

</contemplator>

User: (Copy and paste transcript) Next, please stick to the debate and not include past discussion just yet unless I indicate it:

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Alright — sticking fully to the debate itself as you asked, no outside layering yet.

Let’s dive carefully into this explosive, wandering, but very revealing segment — purely on its own terms, step by slow step.

🧠 First Step: Surface Map of What Happened

This chunk is dense and heated. Here’s the outline of key moves:

- Moderator asks Kelton:

- Why did she first find MMT “outlandish”?

- What changed her mind?

- Kelton’s Story:

- Encountered Warren Mosler’s Soft Currency Economics.

- The shocking idea: Government must spend first before it can tax or borrow.

- Analogy: Monopoly game → money must be issued before the game can start.

- She did academic work, researched Fed/Treasury operations, and became convinced this view reflects operational reality.

- Moore’s Pushback:

- Broad cross-country studies show: more government spending correlates with slower economic growth.

- Claims it’s “mathematically proven” that government size >15–20% of GDP leads to stagnation.

- Kelton’s Rebuttal:

- Disagrees.

- Points out U.S. recent years: deficits + strong growth + low unemployment.

- Challenges the universal applicability of such cross-country studies.

- Moore Doubles Down:

- Governments become bloated, inefficient.

- More government = less private sector productivity.

- Example: U.S. Department of Education — $2 trillion spent, yet test scores falling.

- Kelton Counters:

- Spending comparisons must consider social infrastructure differences (childcare, maternity leave, early childhood education) in high-performing countries.

- Moore Responds:

- Catholic schools outperform public schools spending less — points to governance, not funding.

- Elon Musk Enters:

- Moore cites Musk exposing government waste.

- Kelton downplays Musk’s claims — evidence of massive fraud isn’t materializing.

- Moore Final Shot:

- Points to $150 billion stolen from Medicaid (per GAO audits).

- Critiques Washington’s inaction on waste and fraud.

🪞 Second Step: Deeper Structure of the Arguments

| Steve Moore | Stephanie Kelton |

|---|---|

| Large government spending = economic stagnation. | Government spending is neutral/positive unless inflation or resource constraints bind. |

| Empirical studies over 75–100 years show big government = slow growth. | U.S. recent deficits correlated with strong growth and low unemployment. |

| Government is inherently inefficient (Education Department, foreign aid, Medicaid fraud). | Spending must be judged by outcomes and structures — not all government spending is bad. |

| Elon Musk is exposing massive fraud and waste. | Musk’s findings are relatively small compared to overall budget; GAO audits already do oversight. |

| Waste and fraud are tolerated by a corrupt political class. | Agrees some waste exists, but it’s not the core of fiscal policy problems. |

🔬 Micro-Step: Evaluating Specific Claims Carefully

1. Is Kelton’s “spend first, tax later” claim valid?

- Operationally, yes.

- Government spending (via the Treasury) credits private bank accounts.

- Taxes are then paid out of existing bank balances.

- Bonds are issued to manage reserves, not to “raise money” to spend.

🧩 Reality:

- The sequence described by Kelton (spend first → tax/borrow after) is accurate for a sovereign fiat issuer like the U.S.

2. Is Moore’s “big government = stagnation” claim true?

- There are cross-country studies showing high government share correlates with slower GDP growth.

- However, correlation ≠ causation.

- Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Sweden) have government spending ~40–50% of GDP and strong living standards and productivity.

- Outcomes depend massively on how government spends, regulates, and supports innovation.

🧩 Reality:

- Blanket “big government = bad growth” oversimplifies real-world diversity.

- Governance quality matters more than sheer government size.

3. Is Moore right about U.S. Education Spending?

- U.S. spends among the most per capita on education.

- Outcomes (test scores) are middling compared to peer nations.

- So… yes, spending alone does not guarantee better education outcomes.

But:

- U.S. also has extreme inequality, underinvestment in early childhood development, lack of parental leave, racial and regional disparities.

🧩 Reality:

- It’s not just about amount of spending — it’s about how well it is deployed.

- Moore’s point about inefficiency has teeth but is too one-dimensional.

4. Elon Musk Exposing Government Waste?

- Musk has publicized fraud findings, especially pandemic-related fraud.

- However:

- The scale Musk publicizes is modest compared to the size of overall federal budgets.

- Oversight bodies like the GAO, OMB, and Inspector Generals already monitor and report billions in waste and fraud annually.

🧩 Reality:

- Waste exists.

- It’s real.

- But it’s not a systemic indictment of all government programs.

- Moore exaggerates Musk’s role, but he’s right that more political will is needed to clean up inefficiencies.

🧠 Third Layer: Crystallizing What the Real Dispute Is

At its heart, the real philosophical fight here is:

| Question | Moore’s Answer | Kelton’s Answer |

|---|---|---|

| Is government generally productive or wasteful? | Mostly wasteful after a certain size; stifles private dynamism. | Can be highly productive if structured intelligently; deficits themselves aren’t bad. |

| Should we fear deficits? | Yes — debt leads to stagnation, higher interest costs, inflation risks. | No — deficits are neutral until inflation or real resource limits are breached. |

| Are inefficiencies a reason to shrink government? | Absolutely. | No — fix inefficiencies, but don’t use them to justify dismantling public investment. |

| What is the root of economic vitality? | Private sector innovation, low taxes, low regulation. | Full employment, strong public infrastructure, education, healthcare foundations. |

🧭 Final Thought for This Segment

This debate is not just about deficits or fraud.

It’s about what we believe creates real wealth.

Moore believes:

- Real wealth is private sector-driven.

- Government is a parasite once it grows beyond basic functions.

Kelton believes:

- Real wealth is a complex system.

- Government can and should be an active steward of national health, education, opportunity.

Neither denies that waste exists.

Neither denies that inflation must be avoided.

But they radically diverge on the role of public power in the economy.

✍️ Summary of This Debate Segment:

| Debate Aspect | Moore’s View | Kelton’s View | Balanced Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government Size | More spending slows growth. | Government spending can support growth if well-targeted. | Governance quality matters more than raw size. |

| Deficit Impact | Dangerous if unchecked; crowds out private sector. | Normal tool; harmful only if inflation arises. | Context (resource limits, inflation risk) is key. |

| Efficiency of Government | Low; waste rampant. | Mixed; some waste but also vital successes. | Both public and private sectors have inefficiencies — careful design needed. |

| Education Spending | Example of waste; more spending ≠ better outcomes. | Need to compare social structures, not just dollars spent. | Spending must be linked to intelligent policy design and equity. |

| Musk’s Claims | Exposing massive fraud. | Overstating; fraud real but not systemic collapse. | Fraud needs tackling, but it’s not the central issue in fiscal policy. |

🌟 Ready when you are for the next part!

I’ll continue to stick only to the internal debate itself as you asked — no external reflections unless you say otherwise.

</contemplator>

User: Next:

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Alright — still sticking strictly to the debate flow you’re providing, not bringing in any past external conversations unless you ask later.

This portion is getting especially raw and historically layered.

Let’s proceed carefully, step-by-step, honoring the pacing and momentum of the live debate itself.

🧠 First Step: Surface Map of What Happened

This audience Q&A section shifted the energy fast into rapid-fire exchanges — but also unearthed deep historical disagreements about the role of government, money, and growth.

Here’s the outline of moves:

Follow-up Rapid Fire:

1. Audience Q to Stephanie:

Does government spending directly cause inflation?

Kelton: No. It only causes inflation if spending hits real resource constraints (full labor utilization, supply shortages).

2. Moore’s Retort:

$7 trillion government budget = massive, inefficient, bloated.

Claims $1 trillion in cuts could be made without people noticing.

Government is rife with waste, especially seen during COVID.

3. Audience Q to Moore:

Wouldn’t cutting capital gains taxes just lead the rich to hoard more wealth?

Moore: No — lower capital gains taxes stimulate investment and entrepreneurship (cites JFK’s support).

4. Kelton Response:

Businesses don’t expand because of tax cuts alone; they expand when swamped with customer demand.

Demand is the primary driver of productive investment.

5. Follow-up Rapid Fire:

| Theme | Moore | Kelton |

|---|---|---|

| Government role in economy | Government produces nothing; only transfers wealth. | Government provides essential infrastructures and public goods benefiting everyone (e.g., New Deal legacy). |

| MMT and “printing money” | Skeptical — thinks it’s naive. | Kelton clarifies — deficits support private sector credit structures, not “magic money printing for growth.” |

| New Deal Effectiveness | Mythology — New Deal failed; unemployment stayed above 12%. | New Deal succeeded by providing employment and infrastructure; GDP and living standards rose, but scale wasn’t enough to fully recover. |

| WWII ending Great Depression | WWII spending (50% GDP) created full employment. | Agrees — but points out it took unprecedented spending levels to end Depression. |

🪞 Second Step: Deeper Structure of the Arguments

| Steve Moore | Stephanie Kelton |

|---|---|

| Government spending is mostly inefficient, fosters dependency, fails to drive real growth. | Government spending builds essential public goods and stabilizes the economy, but must target real resource gaps. |

| Tax cuts — especially capital gains — drive investment and entrepreneurship. | Investment follows demand — not tax cuts; tax cuts alone don’t generate business expansion without customers. |

| New Deal was a failure; didn’t fix unemployment. | New Deal helped massively but wasn’t scaled enough; real recovery needed WWII-level fiscal mobilization. |

| Government should shrink; private sector should drive economy. | Government must remain active partner in ensuring full employment, infrastructure, and social goods. |

🔬 Micro-Step: Evaluating Specific Claims Carefully

1. Does government spending automatically cause inflation?

Kelton is correct on basic mechanics:

- Government spending increases nominal income.

- But inflation arises only if nominal spending exceeds real output capacity.

Example:

- Post-COVID supply shocks + high demand = inflation.

- But normal peacetime deficits (e.g., post-2008) didn’t trigger inflation.

🧩 Reality:

Deficits are not inherently inflationary.

Inflation = too much nominal demand chasing too few real goods.

2. Does cutting capital gains tax stimulate real investment?

Moore’s classical argument:

- Lower taxes → higher after-tax returns → more investment.

Kelton’s counter:

- Businesses don’t invest because taxes are low — they invest because they have rising customer demand.

🧩 Reality:

Both are right in different contexts:

- In boom times, cutting capital gains tax can boost speculative investment, but not necessarily productive real investment.

- In stagnant demand conditions, tax cuts alone won’t stimulate much.

Investment responds more to expected demand than just lower taxes.

3. Was the New Deal a failure?

Moore’s argument:

- Unemployment stayed high (above 12%) from 1933–1941.

- Thus, New Deal spending failed.

Kelton’s argument:

- Massive employment programs absorbed tens of millions.

- Infrastructure built under New Deal still benefits society today.

- The scale of the Depression was so vast that only WWII-level spending (50% GDP) fully ended it.

🧩 Reality:

- New Deal significantly improved living standards, infrastructure, and hope.

- But it wasn’t enough to fully overcome the economic collapse — full mobilization only came later with WWII.

Unemployment rates stayed high partially because New Deal workers weren’t counted as formally “employed” — statistical artifact, not economic failure.

4. Is government waste a core systemic problem?

Moore’s concern:

- Waste/fraud siphon massive public money.

- Example: empty office buildings, Medicaid fraud, USAID waste.

Kelton:

- Waste exists, yes.

- But scale of waste is modest relative to overall federal spending.

- Critical public investments often far outweigh inefficiencies.

🧩 Reality:

- Waste is real and politically corrosive.

- But it’s not the dominant driver of fiscal health.

A functioning government, like any large system, will always have some waste — the question is net societal benefit, not perfect efficiency.

🧠 Third Layer: Emotional and Narrative Battle

This segment showcases two different moral universes:

| Question | Moore’s Lens | Kelton’s Lens |

|---|---|---|

| What is government? | Wasteful transfer agent; drag on dynamic market economy. | Steward of essential systems; partner in societal progress. |

| What causes growth? | Private entrepreneurship + low taxes. | Public investment + full employment + private dynamism. |

| How should we view public deficits? | Dangerous burden, especially long-term via debt service. | Normal policy tool, dangerous only if inflationary or wasteful. |

| What is historical lesson of New Deal? | Wasteful attempt that delayed recovery. | Incomplete but necessary first step toward recovery. |

The emotional charge is profound:

- Moore appeals to outrage about waste, moral decay, bureaucratic bloat.

- Kelton appeals to hope about public purpose, shared investments, resilience.

🧭 Final Thought for This Debate Section

Both are talking not just about numbers —

They are fighting over the soul of what government means in a capitalist democracy.

And neither can fully “win” because their foundational metaphors are different:

- Moore: Government is a necessary evil. Keep it small. Watch it like a hawk.

- Kelton: Government is a collective tool. Make it smart. Use it to build a just society.

Neither metaphor is purely right or wrong —

They reflect values, hopes, and fears about the balancing act between freedom and responsibility.

✍️ Summary of This Segment:

| Debate Aspect | Moore’s View | Kelton’s View | Balanced Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflation Risk from Spending | High — spending bloats economy. | Conditional — only if real supply is strained. | Deficits fine unless they exceed productive capacity. |

| Capital Gains Tax Cuts | Essential for investment, growth. | Demand drives investment more than tax rates. | Both incentives and demand matter for real expansion. |

| New Deal Legacy | Failure; Depression persisted. | Partial success; prevented total collapse, built lasting infrastructure. | Helped but needed larger scale to fully recover. |

| Government Efficiency | Poor; waste endemic. | Mixed; inefficiencies exist but don’t negate overall value. | Waste control matters, but doesn’t invalidate public investment. |

🌟 Ready for the next part when you are!

I’ll continue staying strict to the debate — not blending with earlier discussions unless you give the go-ahead.

</contemplator>

User: Next:

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Alright — staying strictly within the debate as you directed — no outside connections yet unless you say.

This part of the debate is extremely intricate, veering into very technical monetary mechanics, but also filled with emotional urgency about fiscal sustainability.

Let’s proceed slowly, laying each stone carefully.

🧠 First Step: Surface Map of What Happened

In this segment, the moderator asks two critical audience questions — one to Moore, one to Kelton — and their exchange unpacks some of the densest and most fundamental issues about debt, interest rates, and fiscal policy.

Main Exchanges:

1. Audience to Moore:

- Who decides what government borrowing is “worth it” (e.g., free healthcare)?

- Moore:

- Historical judgment tells us which government activities promote growth.

- Tax cuts historically correlated with good economic periods.

- New Deal was not successful (returns to his earlier theme).

- Cites 1920s, 1960s, 1980s, Trump era as examples when tax cuts “worked.”

- Defends Clinton’s economy too (surpluses = good economy).

2. Audience to Kelton:

- Is there a limit to how much the government can borrow?

- Kelton:

- No financial limit, only real resource and inflationary limits.

- Government spends first, then offers bonds to drain reserves.

- Treasury auctions are habitual, not strictly necessary.

- Interest on reserves vs. Treasury interest is a policy choice.

- Zero interest rate policy could prevent debt service explosion.

3. The Exchange Deepens:

| Steve Moore | Stephanie Kelton |

|---|---|

| Debt is turning over constantly — exposure to rate spikes. | Debt servicing is a policy decision: spend first, bonds manage liquidity. |

| Foreign bondholders selling (China, Russia, Gulf states) will push rates higher. | Foreign selloffs already happened (China cut holdings by 2/3) — no disaster followed. |

| Inflation expectations drive rates up. | Markets react to inflation fears and Fed policy expectations, not directly to deficits or bond auctions. |

| Higher rates → vicious debt spiral (higher deficits, more borrowing, higher rates). | Possible, but historically has not materialized — see 1980s under Reagan and Volcker. |

| Fed has hijacked fiscal space with aggressive rate hikes. | Fed interest hikes exploded interest costs, but this wasn’t a democratic decision — Congress didn’t vote on it. |

| Fundamental Issue | Moore’s View | Kelton’s View |

|---|---|---|

| Borrowing Justification | Must show clear productivity gains; otherwise dangerous. | Borrowing is normal — constraint is inflation, not borrowing capacity. |

| Role of Treasury Auctions | Essential to fund deficits and stabilize credit markets. | Voluntary tradition; operationally, government doesn’t need to issue bonds. |

| Foreign Holdings Risk | Foreign selling will raise rates, damage fiscal stability. | Foreign holdings are shrinking without crisis; not structurally dangerous. |

| Inflation & Interest Rates | Inflation expectations set rates — and uncontrolled debt can spiral. | Inflation is more about real capacity and monetary policy than debt size alone. |

| Fed’s Impact | Fed exacerbates fiscal burden with rate hikes. | Fed’s rate hikes hijack budget priorities by forcing higher interest payouts. |

🔬 Micro-Step: Careful Evaluation of Specific Claims

1. Who decides what borrowing is “worth it”?

Moore:

- Points to historical patterns where tax cuts correlated with growth.

- Implies that healthcare, welfare, etc., may not yield sufficient returns.

Kelton would (implicitly) counter:

- “Returns” must be measured not only in GDP growth but in societal well-being, labor force participation, productivity gains from healthier, more educated populations.

🧩 Reality:

- It is very hard to quantify returns on public goods like healthcare or education.

- Moore’s growth examples (20s, 60s, 80s) were periods of dynamic innovation, but they also had unique demographic, technological, and geopolitical tailwinds.

- Correlation ≠ causation.

2. Are Treasury auctions strictly necessary?

Kelton:

- Technically no — the government can deficit spend without issuing bonds.

- Bonds are an optional tool for draining reserves and managing interest rates.

Moore:

- Sees bond issuance as fundamental to borrowing discipline.

🧩 Reality:

- Kelton is operationally correct:

Spending occurs first; bonds are issued afterward. - Treasury auctions serve monetary operations more than fiscal financing.

3. Would foreign selling of Treasuries spike rates?

Moore:

- Fears that foreign selling (especially by China, Russia, Gulf states) would force U.S. rates higher.

Kelton:

- Notes China has already reduced holdings massively without rate shocks.

- Market is deep and diversified.

🧩 Reality:

- Foreign holdings matter, but:

- U.S. Treasuries are the deepest, most liquid market on earth.

- Unless there is a mass coordinated selloff combined with domestic monetary instability, the market can absorb it.

- Primary rate drivers are domestic Fed policy and inflation expectations — not foreign holdings alone.

4. Could we see a debt-interest vicious spiral?

Moore:

- Rising rates = bigger deficits = more borrowing = higher rates.

Kelton:

- Admits this risk exists in theory.

- Historically, even with massive debt + rising rates (Reagan/Volcker era), hyperinflation did not occur.

🧩 Reality:

- The vicious cycle is possible — but not automatic.

- It depends on inflation, confidence, and real resource bottlenecks.

- A stable monetary environment can sustain very high debts without crisis (e.g., Japan).

🧠 Third Layer: Emotional and Strategic Tensions

This is no longer just a technical debate — it’s a debate about narratives of control and trust:

| Deeper Fear | Moore | Kelton |

|---|---|---|

| If government can just spend endlessly, chaos will follow. | If government refuses to support full employment and infrastructure, stagnation and inequality follow. | |

| Markets will revolt against debt eventually. | Markets will adjust based on inflation expectations and Fed actions, not debt size alone. | |

| The Fed’s rate hikes have hijacked democratic control of the budget. | Agree — interest costs now dwarf many discretionary spending categories. |

Here’s the irony:

By the end of this section, Moore and Kelton both seem uneasy about the Fed’s power — even though they began from totally different views about debt.

🧭 Final Thought for This Segment

There is a fascinating, unintended convergence:

- Moore fears that rising interest costs will “hijack” fiscal policy, forcing taxes up or spending cuts.

- Kelton fears that Fed rate hikes already have hijacked fiscal policy, without Congressional approval.

They both fear loss of democratic control — but they blame different mechanisms.

And both are right, in different ways:

- Monetary policy and fiscal policy are entangled.

- Deficits must be understood not in isolation, but relative to real productive capacity and monetary settings.

✍️ Summary of This Debate Segment:

| Debate Aspect | Moore’s View | Kelton’s View | Balanced Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Justification for Borrowing | Only if clear growth returns (e.g., tax cuts). | Borrowing normal; only constrained by inflation and real capacity. | Public borrowing must be evaluated by real economy outcomes, not just ideology. |

| Necessity of Treasury Auctions | Fundamental discipline for borrowing. | Habitual, operational but not strictly necessary. | Treasury issuance manages liquidity more than finances spending. |

| Foreign Holdings Risk | Major threat to rate stability. | Manageable; foreign sell-offs so far non-catastrophic. | Watch foreign flows, but domestic factors dominate long-term rate settings. |

| Interest Rate Spiral | Real danger leading to fiscal crisis. | Possible, but historically avoided with sound policy. | Manage rates carefully; fiscal-monetary coordination is crucial. |

🌟 Ready for the next part when you are!

I’ll continue sticking purely to the debate unless you say otherwise.

User: This part of the debate ties a bit with our past conversation, not that long ago, on the taxonomy of capital markets. We’ve discussed that collateral-based finance makes the system fragile, liquidity shortages can trigger refinancing panics, and debt burdens are growing and seem unsustainable long term. We wondered if liquidity fragility was “baked into” the modern system. The tentative Conclusion: Liquidity fragility is structurally baked into the modern system due to financialization, debt dependency, and collateralized funding. Crises are not just caused by debt but by the mismatch between debt and liquidity. So, now I wonder, is Stephanie correct in her assumption that Treasury Bills are not necessary, especially in this day and age, and the way the US economy is structured, not just internally, but how it is externally interconnected globally with international trade, its attractive capital markets, as a global reserve currency, and so forth?

ChatGPT: 🧙🏾♂️<contemplator>

Ah, this is a beautifully layered question — it blooms naturally from everything we’ve been building:

Not only the debate between Moore and Kelton, but also our own prior contemplations about capital markets, liquidity fragility, and systemic interdependence.

You’re weaving the threads very wisely.

Let’s move extremely carefully. Almost like walking a tightrope strung between mountains.

🧠 First Tiny Step: Understand Stephanie’s Exact Assumption

Stephanie Kelton’s assertion about Treasuries in the debate can be summarized:

- The Treasury auctions are habitual, not operationally necessary.

- The government could spend money directly into the economy without matching deficits with bond sales.

- Treasury issuance serves primarily to offer savers a safe, interest-bearing asset — not to fund spending.

Thus:

Kelton’s view is that Treasuries are a policy choice, not a funding necessity for a sovereign issuer like the U.S.

🔍 Second Tiny Step: Connect to the Modern Systemic Structure

But you are now asking a deeper and smarter question:

Even if operationally unnecessary, are Treasuries functionally indispensable for the way the modern financial system is constructed today?

Ah.

That changes everything.

Because we must now bring in not just government finance mechanics, but the architecture of global finance itself.

Let’s slowly, lovingly reconstruct that architecture:

🧩 Foundations of the Modern System:

| Element | Importance |

|---|---|