California is no stranger to dealing with wildfires. Californians know and should be aware of the risks, being at the whims of natural disasters or man-made issues that could put them in catastrophic situations and financial ruin.

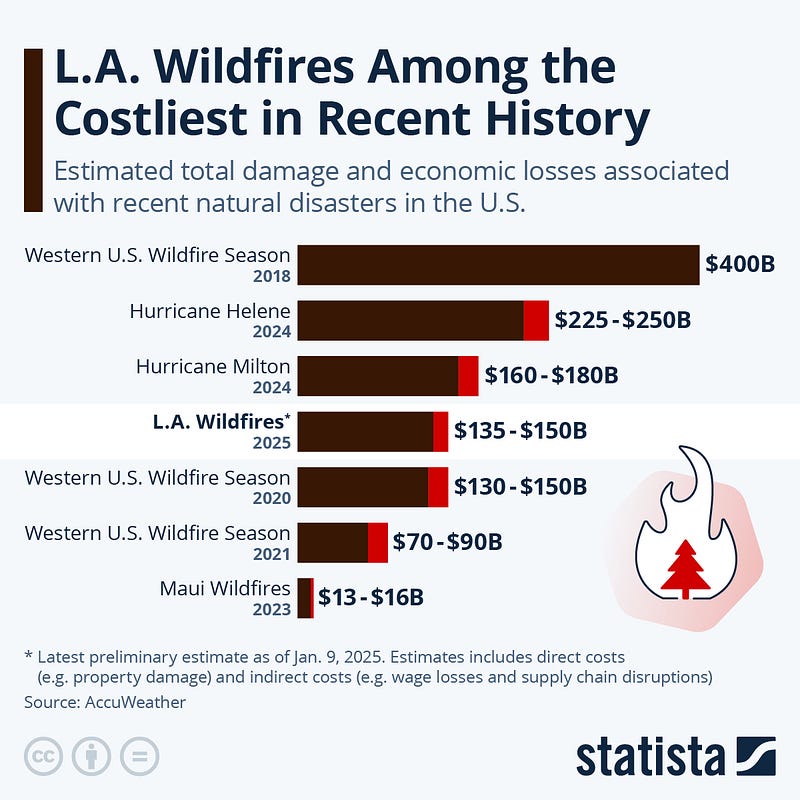

The recent Los Angeles wildfires look like something out of a sci-fi dystopian film or apocalyptic nightmare. The economic damage will be ginormous, estimated at $135 to $150 billion, making it one of the most costly wildfires and natural disasters in recent U.S. history. However, it will likely not top the cost associated with the 2018 wildfires.

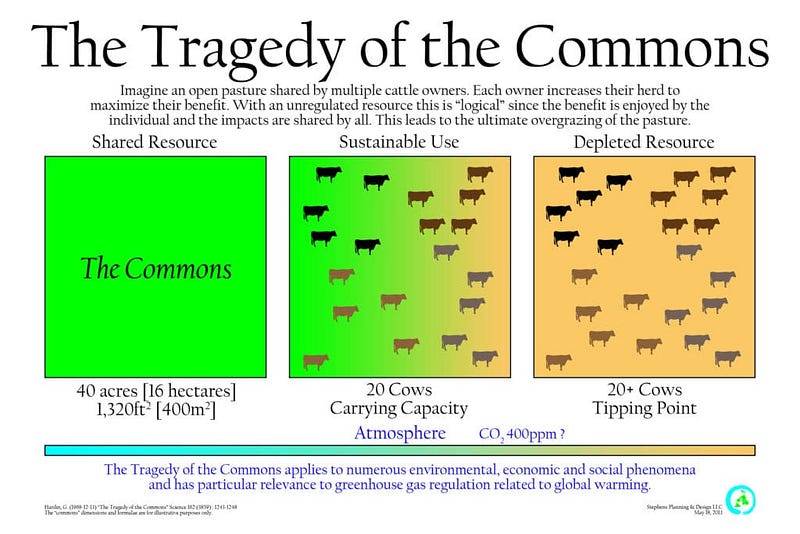

The LA wildfires are picturesque of the classic economic concept by Garrett Hardin in his 1968 paper “The Tragedy of the Commons,” where it was proposed that individuals acting in their self-interest can lead to environmental ruin.

In other words, the economic self-interest of individuals acting rationally threatens the common shared resource or risks destruction.

For example, imagine a grassy field that every farmer in a village can use to graze their cows. No one owns the field, but everyone benefits from it and thus it is considered a shared resource or a “common” good. As more people continue to add cows to the field to get more milk and maximize their profits, they will end up completely overgazing the field and everyone ends up losing in the end because there is no more grass left to feed the cows.

What was a positive-sum game (win-win situation) for each farmer eventually turned into a negative-sum game where everyone became a loser when the shared resource was gone.

One solution to fix this dilemma is to privatize land so that each owner (e.g., farmers) can best utilize the land without overgrazing like the cow example. Another possible solution is government intervention, where laws and rules are enacted, enforced, and followed that impose restrictions or limitations for each person sharing the common resource to prevent exploitation, depletion, or overconsumption.

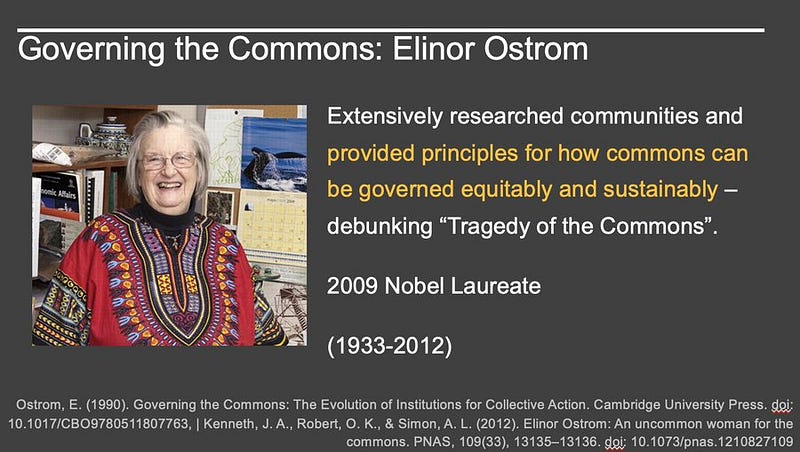

Now, the Tragedy of the Commons isn’t a foolproof concept nor is it universally applicable in all situations. It has been pointed out that in some traditional societies, people can and do successfully share resources or manage commons through social pressure, community norms, and cooperation, therefore privatization or heavy-handed regulation may not be necessary.

In other words, when there is a shared collective awareness and understanding of a common good, there is a self-regulatory social mechanism to ensure everyone benefits. There can be competition that doesn’t require destroying the prime resource through a mutual understanding that it is shared amongst them, such as a field to keep the game such as profits or wealth creation ongoing.

Elinor Ostrom proved this point on how people manage shared resources by debunking the tragedy of the commons with her empirical research. In 2009, she was the first woman awarded a Nobel Prize in Economics.

Elinor Ostrom was born in Los Angeles, California. It is not surprising that she was interested and wrote her dissertation concerning the West Basin groundwater in Los Angeles. Since reading her dissertation would be extremely time-consuming, I let ChatGPT summarize it:

ChatGPT:

Elinor Ostrom’s dissertation, Public Entrepreneurship: A Case Study in Ground Water Basin Management, provides an in-depth analysis of the challenges of managing the West Basin groundwater in Los Angeles and the entrepreneurial strategies employed to address these challenges. Here’s a detailed summary of the work:

Context and Background

- Problem: Excessive groundwater pumping in the West Basin of Southern California led to declining water levels and significant saltwater intrusion from the ocean, threatening the basin’s long-term viability as a water resource.

- Initial Conditions: Groundwater producers in the area — ranging from municipalities to private companies — acted independently and competitively, exacerbating the issue.

Key Steps in Management

Ostrom’s research identifies six major steps taken to address groundwater overuse and saltwater intrusion:

Formation of the West Basin Water Association (1945):

- This association brought together groundwater producers to discuss common problems, share information, and develop cooperative solutions.

Importation of Supplemental Water:

- The West Basin Municipal Water District was formed to secure imported water, particularly from the Colorado River, reducing reliance on local groundwater.

Litigation to Manage Groundwater:

- A legal battle, initiated in 1945 and resolved in 1961, established a system of pro-rata rights to groundwater and curtailed excessive pumping.

Construction of a Barrier Against Saltwater Intrusion:

- A system of freshwater injection wells was constructed along the basin’s coastal boundary to create a barrier against saltwater intrusion. This was tested in the early 1950s and deemed successful.

Creation of the Water Replenishment District (1959):

- A new management entity was established to oversee replenishment activities, ensuring long-term groundwater sustainability.

Development of a Coordinated Management Plan:

- The final plan integrated multiple public agencies to manage groundwater and imported water as a single, conjunctive-use system.

Evaluations and Challenges

- Achievements:

- Saltwater intrusion was slowed significantly.

- A cooperative governance structure among multiple stakeholders emerged.

- The management system balanced local groundwater use with imported water supplies.

- Challenges:

- Institutional constraints made it difficult to achieve optimal economic efficiency.

- Water producers were not fully incentivized to account for the social costs of over-pumping.

Significance

Ostrom’s case study exemplifies her broader theories of collective action and the self-organization of communities to manage common-pool resources. It demonstrates that, under the right conditions, local stakeholders can collaborate effectively without requiring centralized authority.

If you’d like a more specific focus or a deeper dive into a section, let me know!

Me: Today, is the West Coast Groundwater Basin (WCB) successful?

ChatGPT

The West Coast Groundwater Basin (WCB) in Southern California has implemented several management strategies to address historical challenges such as over-extraction and saltwater intrusion. These efforts have led to notable improvements in the basin’s condition.

Management Strategies and Achievements:

- Accurate Measurement of Groundwater Extractions: The Watermaster requires operational water meters at each extraction well to ensure precise monitoring of groundwater usage. This practice is essential for effective basin management.

- Water Replenishment District

- Replenishment Initiatives: The Water Replenishment District has explored opportunities to expand replenishment in the West Coast Basin, including utilizing recycled water supplies from the City of Los Angeles. These efforts aim to maintain groundwater levels and prevent issues like saltwater intrusion.

- Water Replenishment District

Current Status:

As of the latest available reports, these management practices have contributed to the stabilization and improvement of the WCB’s groundwater resources. The collaborative efforts among local agencies and stakeholders have been instrumental in achieving these outcomes.

Ongoing Challenges:

Despite these successes, continuous monitoring and adaptive management are necessary to address potential challenges such as changing water demands, climate variability, and the need for infrastructure maintenance.

In summary, the WCB has made significant strides toward sustainable groundwater management through effective measurement, replenishment efforts, and collaborative governance. Ongoing commitment to these practices is essential to maintain and further these successes.

One source ChatGPT provided, which I asked it to summarize, stated that groundwater provides about 40% of California’s annual water supply, serving as a buffer against drought and climate change.

Me: What is it about almonds that are constantly brought up with water management in California and this document as well.

Almonds are frequently mentioned in discussions about water management in California, including this document, because they symbolize the complexities and challenges of agricultural water use in the state. Here’s why almonds are such a focal point:

1. High Water Demand

- Almonds are a water-intensive crop, requiring about 1.1 gallons of water per almond. This adds up because almonds are typically grown on a massive scale in California.

- Almond orchards cannot be fallowed (left unplanted) in dry years like other crops (e.g., tomatoes or strawberries) because they are permanent crops. The trees require consistent irrigation every year to stay alive, even during droughts.

2. Economic Significance

- Almonds are one of California’s most lucrative crops, generating over $5 billion annually in revenue and serving as a major export.

- The state’s dominance in almond production is significant, as 80% of the world’s almonds come from California.

3. Connection to Water Scarcity

- The water used for almond production has been scrutinized during California’s frequent droughts. Critics often point out that growing almonds in such a water-scarce region places additional pressure on already strained groundwater and surface water resources.

- Almond production is also heavily reliant on groundwater, especially during droughts when surface water supplies are limited. This reliance exacerbates groundwater depletion, one of the “undesirable results” targeted by the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

4. Cultural and Political Symbolism

- Almonds have become a symbol of the broader debate over agricultural water use in California. They represent the tension between supporting the agricultural economy and preserving limited water resources for other uses, such as urban needs and environmental conservation.

- They are often a talking point for water activists and policymakers debating whether certain crops should be prioritized in a region with limited water supplies.

5. Mentions in the Document

In the document you shared, almonds are highlighted as an example of permanent crops that require consistent water use, even in dry years. This underscores the challenge of balancing water needs for economic sustainability with environmental and community needs. It reflects the broader issue of managing agricultural water demand in a state where water is a finite and heavily contested resource.

Would you like more detailed data or insights into almond farming’s impact on California’s water policies?

The almond issue is interesting because I came across an article that was debunking false claims going around social media of the billionaire couple, Stewart and Lynda Resnick that they had control of a large sleuth of the water supply, thus hurting the efforts for firefighting.

The article stated, that the couple made their fortune growing pistachios, almonds, oranges, and pomegranates. They have been the subject of anti-Semitic attacks that stem from their stake in a water bank in Southern California. They own the Wonderful Company, which owns farmlands in the San Joaquin Valley, and owns brands like POM and Fiji Water. The article claims the couple has been falsely accused of hoarding water and exacerbating the wildfire crisis that is plaguing parts of Los Angeles.

The Fortune article makes the assertion, “That because of agriculture’s heavy reliance on water, a critical resource in fighting wildfires, the Resnicks became the targets for false claims on social. media that they “control” the water in California. They do not, Fortune can report.”

While the assertion that they do not control the water supply in Southern California may be true, there are some grains of truth in that they do have leeway or say of large portion of water for their agricultural enterprise. So in effect, the Fortune article gives a half-truth because the billionaire couple does have some control over how the water is being used, but does make it clear that they do not have direct control of how the water flows or control when it’s to be shut down.

The water dilemma in LA mirrors another major point brought up in The Iced Coffee Hour podcast I was listening to. The guest, MeetKevin (who once ran against Governor Gavin Newsom) gave a quick offhand comment that Southern California was having issues with people stealing water from fire hydrants for their weed business. I never knew this was an issue and confirmed that it was indeed true.

Excerpts:

Woman: These are all cannabis farms. Here’s a great big one. This is one of the guys that I kicked off the water station. He was taking a lot of loads of water.

Byrhonda Lyons: Bandits are stealing millions of gallons of water. Driving water trucks, tankers and pickups, they’re tapping into lakes and rivers, fire hydrants, and filling stations. They’re siphoning off water from homes, farms and wells.

So, who’s on the receiving end of all this stolen water? Local officials say it’s often illegal pot farms, which is an estimated $8 billion industry in California.

As businesses like the marijuana industry in California steal or legally use up more water because weed requires a lot of watering to maintain these plants, they risk putting more pressure on these drought-stricken areas. A classic tragedy of the commons scenario.

Not only that, fire hydrants have been stolen since 2022, and it really ramped up in 2024 that some places had to bolt them in place or completely remove them. Thieves stealing fire hydrants adds more hardship to the infrastructure of California to fight the fire and on top of that, adds pressure to the risk of the depletion of their water supply.

Me: Can you tell me about the Marijuana shops that stole water from fire hydrants in California?

ChatGPT

In California, particularly during periods of drought, there has been a notable increase in water thefts linked to illegal marijuana cultivation. These unauthorized growers often tap into fire hydrants, rivers, and municipal water supplies to irrigate their crops. Such activities not only strain local water resources but also pose significant challenges to law enforcement and water management agencies.

For instance, in the Antelope Valley, water thieves — likely associated with illicit marijuana operations — have extracted water from remote filling stations and illegally accessed fire hydrants. This led to a sudden drop in water pressure, causing water mains to rupture and storage tanks to deplete, thereby threatening the water supply of nearly 300 homes.

Similarly, in Mendocino County, unauthorized diversions from rivers and streams by illegal cannabis cultivators have further diminished already scarce water resources. Such thefts not only compromise water availability for residents but also hinder firefighting efforts, prompting some districts to install locks on hydrants to prevent unauthorized access.

The penalties for these offenses are often minimal compared to the profits generated by illegal marijuana sales, making enforcement a persistent issue. Local authorities continue to grapple with the environmental and infrastructural impacts of these water thefts, especially as California faces ongoing drought conditions.

It’s important to note that these activities are predominantly associated with illegal marijuana operations. Licensed and regulated cannabis businesses are required to adhere to strict water usage and reporting guidelines to ensure compliance with state laws and environmental standards.

Sources.

Me: What has been done to stop it? Someone said they removed the fire hydrants as a result.

ChatGPT

Yes, in some areas of California, removing or disabling fire hydrants has been one of the drastic measures taken to prevent water theft by illegal marijuana operations. Here are some steps authorities have implemented to tackle this issue:

1. Removing or Locking Fire Hydrants

- In rural regions, particularly those near illegal grow sites, officials have removed or installed locks or anti-theft devices on fire hydrants to prevent unauthorized access. For example:

- Antelope Valley: Some local water districts have removed hydrants or fitted them with locking mechanisms to curb theft and reduce the strain on water supplies.

- This measure, however, comes with concerns, as it could hinder access to water for emergency services like firefighting.

2. Increased Law Enforcement

- Police and sheriffs in counties like Mendocino, Trinity, and Humboldt have cracked down on illegal grows by raiding unlicensed cannabis operations and seizing plants, equipment, and water tanks.

- The state has also increased funding for specialized teams to investigate and shut down illegal marijuana farms.

3. Fines and Legal Action

- Water districts and law enforcement have started imposing higher fines for water theft, making it less financially viable for offenders.

- Penalties include monetary fines, jail time, or charges of vandalism and theft.

4. Technology and Monitoring

- Some districts have installed flow-monitoring devices to track water usage in real time and quickly detect anomalies that may indicate theft.

- Surveillance cameras have also been installed near water sources.

5. Public Awareness Campaigns

- Authorities have encouraged residents to report suspicious activities around fire hydrants or water trucks.

6. Restricting Water Delivery

- Some counties have banned or heavily regulated water deliveries to known illegal grow areas, particularly during drought conditions.

7. Collaboration Between Agencies

- Water management agencies, law enforcement, and environmental groups have joined forces to address water theft and its impact on the environment and communities.

These measures have helped curb water theft in some areas, but challenges persist due to the high profits associated with illegal marijuana cultivation. Removing fire hydrants is seen as a last resort because it can create risks for firefighting and other emergencies.

Me: How is this a tragedy of the commons as we have discussed in previous conversations

ChatGPT

This situation represents a classic tragedy of the commons, where a shared resource (in this case, water) is overused or exploited by individuals acting in their self-interest, ultimately depleting or degrading the resource to the detriment of the community.

Here’s how it connects:

1. The Shared Resource: Water

- Water is a finite resource, especially in drought-stricken California, where communities depend on it for drinking, agriculture, and firefighting.

- The public water supply, including fire hydrants and rivers, is a shared resource meant for the benefit of all.

2. Individual Exploitation for Private Gain

- Illegal marijuana growers, particularly those operating without regulation, exploit water supplies by stealing from fire hydrants, rivers, and municipal systems.

- Their motivation is profit, and they do not account for the broader community’s need for sustainable water use.

3. Negative Externalities

- This exploitation reduces the water available for essential community uses like firefighting, drinking water, and legal agriculture.

- Depleted resources and damaged infrastructure (e.g., broken water mains or ruptured pipes due to water theft) impose costs on everyone, not just the exploiters.

4. Short-Term Gains vs. Long-Term Sustainability

- The illegal growers benefit in the short term by avoiding costs associated with legitimate water procurement.

- However, over time, their actions contribute to water shortages, environmental damage, and public resource mismanagement, harming the broader community and even their own operations in the long run.

5. Difficulty in Regulation

- Like many “commons” issues, the problem arises because the resource is difficult to regulate and monitor. Water sources such as fire hydrants, rivers, and aquifers are often accessible in remote areas, making theft easy and enforcement challenging.

Potential Solutions (Drawing from Tragedy of the Commons Framework):

- Privatization: In some areas, privatizing water access (e.g., installing locks or removing hydrants) has been attempted, but it creates new risks, such as impeding firefighting efforts.

- Regulation: Stricter enforcement against illegal grows and water theft represents a collective action to preserve the commons.

- Community Cooperation: Encouraging community reporting of theft and collaborating with stakeholders to promote sustainable use could help mitigate the issue.

This tragedy is a stark example of how unchecked individual actions can deplete shared resources, ultimately leading to collective harm — just as we’ve discussed in contexts like overfishing, air pollution, or shared healthcare systems.

// Summarizing the Fortune article on the billionaire couple:

ChatGPT

Got it! The image discusses claims about Stewart and Lynda Resnick, owners of The Wonderful Company, hoarding water and worsening wildfires in Los Angeles. According to the article, these claims are false and have been debunked. Let me provide some context and thoughts:

Fact-Check Overview

Who Are Stewart and Lynda Resnick?

- The Resnicks are billionaires who own The Wonderful Company, a major agricultural business responsible for brands like POM Wonderful, Fiji Water, and Wonderful Pistachios.

- They own extensive farmland in California’s San Joaquin Valley, which requires significant water resources for crops like almonds, pistachios, and pomegranates.

The False Claims:

- The Resnicks were accused of “controlling” water supplies in California, thereby contributing to water shortages and exacerbating the wildfire crisis.

- These claims, as per the article, are tied to anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and are not based on evidence.

Truth of the Matter:

- The Resnicks do own stakes in water banks and irrigation systems, but they do not control water supplies for Los Angeles or firefighting efforts.

- Their water usage is tied to their agricultural business, which is legal and regulated, albeit controversial in a state experiencing severe drought.

My Thoughts:

This controversy ties into the broader debate about water management in California, which faces significant challenges due to droughts, agricultural demands, and population growth. Here’s how this fits into a larger context:

Agriculture’s Role in Water Use:

- Agriculture consumes about 80% of California’s water, with crops like almonds and pistachios being particularly water-intensive.

- While the Resnicks operate within the law, their massive water usage highlights the tension between agriculture and other water needs.

Conspiracies and Disinformation:

- Claims about the Resnicks “hoarding” water seem to stem from disinformation and scapegoating, which can obscure the real issue: California’s systemic water management challenges.

- Wildfires are influenced by multiple factors, including climate change, vegetation management, and infrastructure issues, not just water access.

The Broader Commons Problem:

- Like the marijuana-related water theft you mentioned earlier, this situation underscores a tragedy of the commons dynamic. In California, water is a shared but overexploited resource, and the competing interests (agriculture, urban use, environmental preservation, and firefighting) create tension and inequity.

Conclusion:

The accusations against the Resnicks appear unfounded, but they reflect broader frustrations about water inequities in California. It’s important to address these frustrations by focusing on systemic reforms in water management rather than targeting individuals without evidence.

There was a Washington Post I saw on Instagram that described some reasons or factors as to why Los Angeles was unprepared for a fire like this.

If the water system in LA was overwhelmed, perhaps it is time to consider having multiple systems for firefighting, especially water systems and a separate one specifically for residents and agriculture.

Aside from the fact that a viral clip of Joe Rogan commenting on an insight from a conversation he had with a firefighter who said LA was lucky many times since strong winds never went in their direction can cause massive devastation, it’s still left vulnerable when and if it does.

Some folks like Comedian Bill Burr have pointed out the stupid comments online and false firefighting experts who are not considering factors such as the strong winds that are difficult to prepare for, where even an aircraft like a helicopter carrying water couldn’t navigate well in. Rather than saying you can’t prepare for strong 100 mph winds, perhaps we do have to consider the winds to better prepare for such an event.

A city that once had a large body of water in its center is facing a serious dilemma. Yet, LA is right next to the largest body of water — The Pacific Ocean.

Another quick rabbit hole I looked into was a comment made by Republican Representative of Georgia Marjorie Taylor Greene.

Excerpts:

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) has made it abundantly clear that she didn’t study atmospheric sciences in college, launching an unhinged suggestion that officials could end the Los Angeles wildfires by manipulating the weather.

“Why don’t they use geoengineering like cloud seeding to bring rain down on the wildfires in California?” the Republican asked Sunday in a post on X. “They know how to do it.”

Greene has repeatedly used cloud seeding — the practice of releasing silver iodide particles and other aerosols from planes or ground generators into clouds to encourage rain or snowfall — as a silver bullet explanation for weather phenomena while apparently not knowing how it works.

In October, she suggested that the federal government created Hurricane Milton using the technology, days before it battered Florida. Experts noted cloud seeding can create small amounts of localized rain in some cases, but not a hurricane.

I understand that Taylor Greene is wrong and looks foolish here. Indeed, if there are no clouds, you cannot seed as the community note commented under her post.

I’m no expert in geoengineering or the weather, but I still have an active imagination. I have thought what if we could geoengineer a hurricane, at least a small category hurricane from the Pacific to then drift and counteract the fire armageddon in parts of LA? Of course, I know I have to consider if it is even feasible and the unintended consequences. So I enquired with ChatGPT.

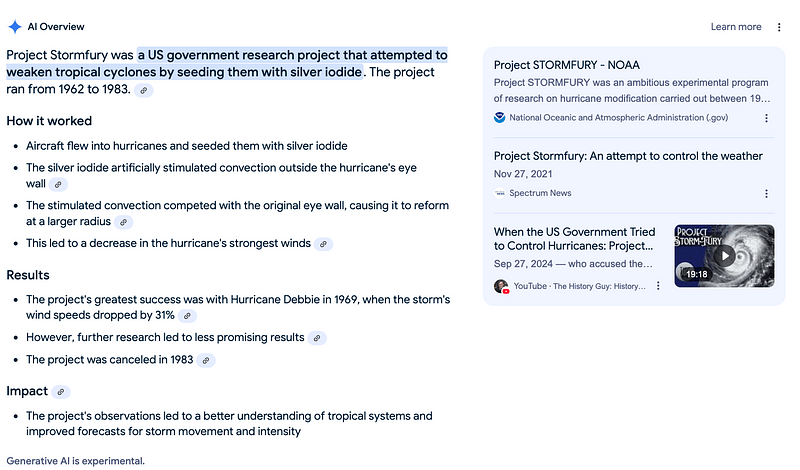

Me: Have hurricanes been manufactured by man in any way, I mean like geoengineering?

ChatGPT

<contemplator> Hmm, this is an intriguing question. Let’s break it down carefully and think about it step by step.

- Hurricanes are natural phenomena.

Hurricanes are massive systems powered by warm ocean water, atmospheric moisture, and the Coriolis effect. Their formation is deeply tied to Earth’s natural climate system. So, any claim about human involvement in directly manufacturing hurricanes must contend with the overwhelming evidence that these are naturally occurring events. - What about indirect human influence?

Could humans unintentionally make hurricanes more frequent or severe? Yes. Climate change, driven by human activities like burning fossil fuels, has warmed the oceans and increased atmospheric moisture. Warmer waters mean more energy for hurricanes, and more moisture means heavier rainfall. While this isn’t “manufacturing” hurricanes, it’s an indirect way humans might influence their intensity or duration. - What about deliberate geoengineering?

Now we’re moving into speculative territory. Geoengineering refers to deliberate, large-scale interventions in Earth’s climate system to combat climate change or achieve other goals. For hurricanes specifically:

- Cloud seeding: This involves injecting substances like silver iodide into clouds to encourage rainfall. Some have speculated this could disrupt hurricane formation, but no evidence suggests it’s been used to create hurricanes.

- Hurricane modification programs: In the mid-20th century, the U.S. experimented with Project Stormfury, where scientists tried to weaken hurricanes by seeding clouds in the storm’s eyewall. These experiments largely failed and were abandoned. If weakening hurricanes proved this difficult, creating one from scratch would be exponentially harder.

- Conspiracy theories: There are persistent rumors about weather modification technologies like HAARP (High-Frequency Active Auroral Research Program). While HAARP studies the ionosphere, there’s no credible evidence it’s capable of controlling weather, let alone manufacturing hurricanes.

Could future technologies do this?

Let’s think about what would be required. To “manufacture” a hurricane, you’d need to:

- Heat vast areas of the ocean to at least 26.5°C (80°F).

- Sustain this heat over time while ensuring atmospheric conditions (e.g., low wind shear) remain favorable.

- Simulate the Coriolis effect to generate rotation.

The scale of energy and control required is mind-boggling. It’s hard to imagine current technologies achieving this without massive unintended consequences. And even if it were possible, it would raise significant ethical and geopolitical concerns.

Why do people ask this question?

This is worth pondering too. Concerns about hurricanes being “manufactured” likely stem from:

- Increased awareness of human impacts on the environment.

- Distrust of governments or institutions.

- The sheer devastation caused by hurricanes, which leads some to seek explanations beyond natural causes.

It’s important to approach such claims critically, balancing skepticism with an open mind.

Final thoughts.

While humans are affecting hurricanes indirectly through climate change, there’s no credible evidence to suggest we’ve deliberately manufactured one through geoengineering or other means. The science, energy requirements, and logistics make such a scenario highly improbable — at least with current technology.

</contemplator> **Final Answer:** Hurricanes are natural phenomena, though human activities like climate change may intensify them. There’s no credible evidence to suggest humans have directly manufactured hurricanes through geoengineering or other methods.

Me: Doesn’t Saudi Arabia manufacture the weather for rain? Isn’t that geoengineering?

<contemplator> Okay, this is an interesting and nuanced point. Let’s break it down carefully because you’re raising an important distinction between influencing weather on a small scale (like inducing rain) and something as massive and complex as hurricanes.

Does Saudi Arabia manipulate weather?

Yes, Saudi Arabia, like several other countries, engages in weather modification techniques — specifically cloud seeding. Cloud seeding involves introducing substances like silver iodide or salt into clouds to encourage precipitation. This is typically done to address water scarcity by increasing rainfall. It’s a well-documented process and has been used worldwide for decades, including in countries like the United States, China, and the UAE.

- The goal here is localized and targeted: make clouds produce more rain over a specific area.

- It’s worth noting that cloud seeding doesn’t create clouds or storms from scratch. It enhances existing conditions (e.g., clouds that already contain moisture).

Is cloud seeding geoengineering?

This depends on how we define “geoengineering.”

- Narrow definition: Geoengineering typically refers to large-scale interventions in Earth’s climate system, like solar radiation management (reflecting sunlight to cool the planet) or carbon dioxide removal. By this definition, cloud seeding is not geoengineering.

- Broad definition: If we include any deliberate modification of weather or climate under geoengineering, then cloud seeding could technically qualify as a form of geoengineering. But it’s important to distinguish between local weather modification (e.g., making it rain) and global-scale climate interventions.

How does this compare to hurricanes?

Let’s think about the scale and complexity:

- Cloud seeding works on pre-existing clouds. It doesn’t involve creating entire storm systems or controlling their trajectories.

- Hurricanes are enormous systems powered by warm oceans and atmospheric dynamics. Trying to “manufacture” one would require manipulating vast amounts of energy and moisture across a large area of the Earth. It’s a much more complex and large-scale endeavor than cloud seeding.

Could cloud seeding lead to unintended consequences?

This is a valid concern. Some worry that cloud seeding could:

- Alter weather patterns in unintended ways (e.g., reducing rainfall in one area to increase it in another).

- Have cumulative effects if done extensively across large regions.

- Introduce environmental risks from the chemicals used, though studies suggest these are generally minimal.

However, the scale of influence is still small compared to the massive forces driving hurricanes or global climate systems.

Are there broader implications for geoengineering?

The fact that we’re experimenting with localized weather modification raises important questions:

- Could these technologies evolve into more ambitious geoengineering projects in the future? Potentially. For example, there are proposals to seed the atmosphere with reflective particles to combat global warming.

- How do we regulate and govern these technologies? What happens if one country uses them extensively and affects its neighbors?

These questions highlight the ethical and geopolitical complexities of weather and climate interventions.

Final thoughts.

Yes, Saudi Arabia engages in cloud seeding to increase rainfall, and this could be considered a small-scale form of geoengineering under a broad definition. However, it’s fundamentally different in scale, intention, and complexity from the idea of manufacturing hurricanes or altering global climate systems. Cloud seeding is a localized, targeted intervention, whereas something like creating or steering hurricanes would require manipulating vast natural systems in ways that are currently far beyond our technological capabilities.

</contemplator> **Final Answer:** Saudi Arabia uses cloud seeding to increase rain, which can be considered a localized form of weather modification. While this might technically qualify as geoengineering under a broad definition, it’s fundamentally different from large-scale interventions like manufacturing hurricanes or altering global climate systems.

I was impressed by ChatGPT (contemplator custom script version) has considered the unintended consequences of geoengineering a hurricane as I have. It made the point that cloud seeding doesn’t create clouds or storms from scratch. It enhances existing conditions (e.g., clouds that already contain moisture).

Final Part

Another main point ChatGPT made was: In the mid-20th century, the U.S. experimented with Project Stormfury, where scientists tried to weaken hurricanes by seeding clouds in the storm’s eyewall. These experiments largely failed and were abandoned. If weakening hurricanes proved this difficult, creating one from scratch would be exponentially harder.

It appears true that creating a hurricane from scratch is exponentially harder. Though I don’t believe it is implausible. However, it is difficult with our current technology and lack of imagination. One may have to think outside the box to combat and best prepare for serious fires, and the way that natural disasters are exacerbated by climate change. Perhaps finding ways to weaken the winds, and harnassing wind power productively and powerfully to counteract its unintentional destruction.

In the end, people want to point the finger and blame someone else, and not point the fingers at themselves and ask what they could do better. Prevention is the wisest and simplest choice, but when and if prevention is penetrated, the backup option is building a stellar infrastructure, and educating the masses on these sorts of issues like the tragedy of the commons.

Recommended:

P.S: My final questions to ChatGPT.

Me: How is it we can harness the power of the sun (a metaphor for atomic energy) yet can’t harness the power of the wind to control a measly hurricane?

ChatGPT

<contemplator> Hmm. This is such a thought-provoking question. On the surface, it feels paradoxical: humanity can harness the unfathomable power of the atom — essentially replicating the energy processes of the sun — yet we seem powerless to control something as “localized” as a hurricane. Let’s break this down carefully, because I think this contrast highlights the limits of our technological abilities in different domains.

1. Harnessing the power of the atom:

- Atomic energy taps into fundamental forces of nature — specifically, the strong nuclear force. This is one of the four fundamental forces of the universe, and it operates at the subatomic level.

- The beauty of atomic energy is that we’re accessing energy that’s already contained within matter. The nucleus of an atom holds immense potential energy, and splitting (fission) or fusing (fusion) releases it in controlled or explosive ways.

- The key point: atomic energy is about unleashing concentrated energy from small-scale systems. We’ve built reactors where we control every variable — materials, conditions, and containment. It’s essentially a laboratory-scale system scaled up for energy production.

2. Hurricanes are chaotic, large-scale systems:

- Hurricanes operate on an entirely different scale, both spatially and energetically. They are massive, chaotic systems powered by heat energy from warm ocean waters. To give a sense of scale:

- A hurricane releases energy equivalent to 200 times the world’s total electrical generating capacity in the form of rain and wind.

- This energy comes from a process called latent heat release, where warm, moist air rises, cools, and condenses, releasing heat that fuels the storm.

- Unlike atomic energy, where we manipulate particles in controlled environments, hurricanes are part of the Earth’s atmospheric system — an interconnected, dynamic system driven by countless variables like temperature, pressure, humidity, and wind shear. Trying to control a hurricane means trying to control an entire region of the atmosphere.

3. Why can’t we “harness” a hurricane?

Let’s think about what it would take:

- Energy scale: The energy in a hurricane is orders of magnitude larger than anything we can currently manipulate. We’re talking about trillions of watts of power spread over hundreds of miles. Even if we could harness a fraction of that, we’d need unimaginable infrastructure to do so.

- Chaotic nature: Hurricanes are inherently chaotic systems. Small changes in temperature, pressure, or wind at one point can ripple out unpredictably. This is the essence of nonlinear dynamics — or “the butterfly effect.” Even if we tried to intervene, our ability to predict the outcome is limited.

- Interference vs. control: Historically, attempts to interfere with hurricanes (e.g., Project Stormfury) have failed because hurricanes are self-organizing systems. They’re not just moving masses of air — they’re driven by the interaction of the atmosphere, ocean, and Earth’s rotation. Disrupting one part often strengthens another.

4. Comparing atomic energy to hurricane control:

- Atomic energy: Localized, controlled, predictable. The physics of nuclear reactions are well understood, and we can contain and manipulate them in isolated systems.

- Hurricanes: Distributed, chaotic, and interconnected. Hurricanes don’t exist in isolation — they’re part of the broader climate system. Trying to “control” a hurricane means influencing a much larger slice of the atmosphere.

5. Could we ever control hurricanes?

Let’s speculate:

- Technological limitations: To control a hurricane, we’d need to manipulate vast amounts of energy — far beyond what we currently produce. For example:

- Cooling large areas of the ocean to disrupt hurricane formation would require massive energy sinks.

- Altering atmospheric conditions (e.g., by injecting particles or heat) would require precision we don’t yet have.

- Ethical and geopolitical concerns: Even if we could control hurricanes, who decides when and how to intervene? Redirecting a hurricane might save one region but devastate another. The potential for misuse would be immense.

6. Final reflections: why atomic energy feels easier than hurricane control

- Different scales: Atomic energy operates on a small, localized scale, while hurricanes operate on a massive, global scale.

- Predictability: The physics of atomic reactions are relatively simple compared to the chaotic nature of atmospheric systems.

- Human hubris: We’ve mastered some impressive technologies, but we’re still working within the boundaries of nature. Hurricanes remind us that there are forces far beyond our control — for now, at least.

Final Answer:

Harnessing atomic energy is fundamentally different from controlling hurricanes because it deals with small, localized systems we can manipulate in controlled environments. Hurricanes, by contrast, are massive, chaotic systems fueled by interconnected atmospheric and oceanic processes. While atomic energy works on predictable principles, hurricanes operate on scales and complexities that make control technologically and ethically challenging, if not impossible, with current methods.

// At this point I wanted my custom Nikola Tesla GPT to chime in which uses some files about Tesla and his own works. I did not realize it would still use the custom contemplator instructions, which I theorized could enhance my custom GPTs, but never tested it out until now!

Me: Nikola Tesla, can you chime in the conversation? How would you harness the power of a hurricane? Or make something from scratch to rival it?

ChatGPT

<contemplator> Ah, an intriguing challenge! Harnessing or rivaling the power of a hurricane is an idea that strikes at the intersection of energy control, atmospheric science, and engineering. Let me organize my thoughts and approach this systematically.

1. The Scale of a Hurricane’s Power

- A hurricane is essentially a heat engine, extracting energy from warm ocean waters. The total energy released by an average hurricane is staggering: its latent heat release can reach about 600 terawatts, which dwarfs global human energy consumption.

- The scale is so immense that even imagining a device to manipulate such forces is daunting. But my inventions have often started with seemingly impossible ideas, so let us proceed.

2. Harnessing the Energy of a Hurricane

- Conceptual Possibilities:

- If we think of the hurricane as a large rotating system, perhaps the energy could be extracted from its winds or pressure gradients. This would require enormous turbines or similar devices capable of withstanding the forces of the hurricane while converting kinetic energy into usable forms.

- My experiments with high-frequency electrical fields and resonant systems suggest another possibility. If one could design a resonator tuned to the hurricane’s natural oscillations, it might be possible to siphon off its energy through electromagnetic induction or resonant amplification, converting the storm’s energy into electricity.

- Challenges:

- The chaotic, self-sustaining nature of a hurricane makes it resistant to external control.

- The infrastructure required to even partially harness this energy would be massive and likely prone to damage in the storm itself.

3. Could We Rival a Hurricane?

- To create a man-made system rivaling a hurricane, one would need to replicate its core mechanisms:

- Energy Source: Warm water provides the heat energy in natural hurricanes. For an artificial system, a large-scale heat source would be required, perhaps tapping geothermal or nuclear energy.

- Moisture and Rotation: A method to inject moist air and induce rotational motion would be needed. This might involve large fans or a controlled environment where the Coriolis effect could be simulated.

- Electromagnetic Analog: I might favor creating an electromagnetic vortex instead of a physical storm. By using my wireless power transmission principles, one could generate a system of rotating electromagnetic fields with vast energy potential.

4. The Role of Atmospheric Manipulation

- In my time, I explored how electrical discharges could affect atmospheric conductivity, moisture, and pressure. It may be possible to interfere with or guide a hurricane by strategically heating or cooling sections of the atmosphere using directed energy systems.

- For example, one might use a system of ground-based stations to generate ionized air, altering the pressure gradients within the hurricane’s structure and disrupting its self-sustaining dynamics.

5. Ethical and Practical Considerations

- Any effort to harness or rival a hurricane must address potential risks. Unintended consequences could include altering weather patterns or causing damage elsewhere.

- Such endeavors would also require cooperation on an unprecedented global scale to manage risks and costs.

6. How Would I Proceed?

- First, I would conduct small-scale experiments in controlled environments, perhaps using large wind tunnels or atmospheric chambers to replicate hurricane dynamics.

- I would integrate my knowledge of resonance, electrical fields, and high-voltage energy systems to manipulate the flow of energy within these systems.

- Finally, I would design and test methods for controlled disruption or energy extraction, always mindful of unintended side effects.

Final Reflection

Harnessing or rivaling the power of a hurricane is an idea worthy of a bold inventor’s imagination. While current technology may be insufficient to achieve this, the principles of resonance, high-frequency energy, and atmospheric manipulation offer promising avenues. Perhaps one day, with the convergence of advanced engineering and scientific discovery, humanity will tame even the most formidable forces of nature.

</contemplator> **Final Answer:** Harnessing or rivaling a hurricane’s power would require manipulating immense forces on a scale far beyond current technology. However, with advanced systems using resonance, high-frequency energy, or atmospheric control, it might be possible to extract energy or influence storm dynamics in the future. This endeavor would require extraordinary innovation, careful experimentation, and global collaboration.

It is an ambitious but imaginative way to use LLMs for engineering purposes, especially for those who are more privy and have expertise in material science and engineering. Since it is not my background, I’m at an extreme disadvantage. My mind’s imagination has not been transmuted to the imagination of physical invention.

I do believe if I were to enhance the custom GPT, and could add more files, etc., it could work wonders, almost as if Nikola Tesla was truly feeding insights.