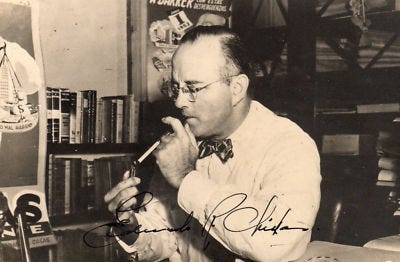

“If I am going to die, I want my last words to be for the Cuban revolution. I am a revolutionary; I love my patria and have contempt for the current regime.” — Eddy Chibás.

Prefix

In 2021, I conducted a quick research report for a course, which I have since revised and edited with the help of AI. The research was inspired by a brief excerpt from the course book, *Cuba: What Everyone Needs To Know* by Julia E. Sweig. The excerpt stated:

“The University of Havana had become the center of outright political gangsterism. Chibás’s weekly radio tirades against the improprieties and corruption of the Auténticos reached a new fever pitch and gained more acolytes for the Orthodox cause. During the summer of 1951, however, Chibás shot and killed himself on the air, in an apparent radio publicity stunt gone wrong. The result was even more political upheaval” (p. 19).

Introduction

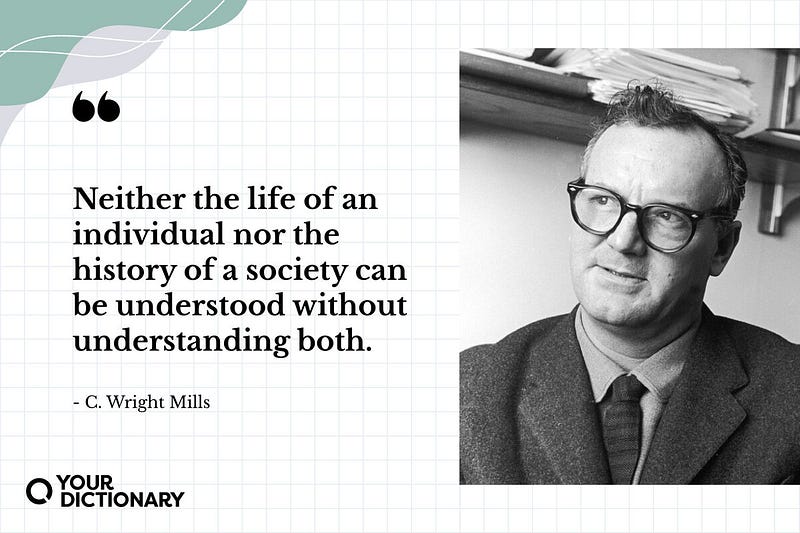

Cuba has long captivated the imaginations of historians, journalists, activists, students, and sociologists. Among them was C. Wright Mills, who visited the island in the 1960s to write a book giving voice to the Cuban Revolutionaries. In one of Mills’ most famous works, “The Sociological Imagination,” he asserts, “Neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.” This highlights the importance of recognizing the connection between personal biography and the broader society in which individuals live, which is the bread & butter to developing the sociological imagination.

The origins of the Cuban Revolution of 1959 can be traced back to the 1920s and 1930s, leading up to that climactic moment. Meanwhile, on the other side of the hemisphere, the Russian Revolution of 1917–1923 established a new social order. The 1920s, known as the Roaring Twenties, was a decade of political and social change marked by rapid industrial and economic growth. The era saw vast consumerism as accumulated wealth allowed people to own innovative products like cars, telephones, and radios. This period of political turmoil, economic prosperity, and irrational exuberance culminated in the crash of 1929, which led to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The socio-political landscape of Cuba was heavily influenced by its neighbor, the United States, particularly through the Platt Amendment, which allowed U.S. intervention and occupation of Cuba until its repeal in 1934. This external control caused an identity crisis in Cuba and culminated in imperialistic constraints as it struggled to develop its independence and establish a unique national identity. This struggle fostered strong nationalist attitudes and, in the 1920s, led to the rise of student movements, political parties, labor strikes, insurrections, and widespread violence that affected everyone involved.

Prominent figures that materialized and left their mark in Cuban history include José Martí, Gerardo Machado, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, Fulgencio Batista, Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro, Julio Antonio Mella, and many others who shaped Cuban consciousness. However, fewer people are aware of the lesser-known but significant figure, Eduardo Chibás (1907–1951). Chibás was a major catalyst in the Cuban political discourse. It could be said you could learn all that there is to know about ‘politics’ by studying Cuba’s tumultuous time and studying Chibás.

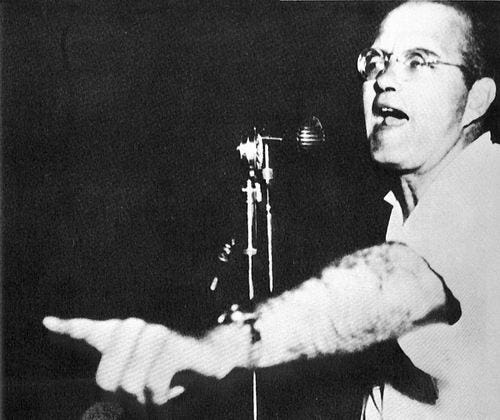

Chibás was a popular radio personality known for his volcanic temperament, relentless attacks on corruption, and fervent nationalist sentiments. He often accused those in power of corruption without providing concrete evidence. Fidel Castro once declared, “Without him, the revolution wouldn’t be possible.” He was a polarizing figure, adored by some and hated by others. Chibás was anti-imperialist, and anti-communist, and made many enemies, yet he managed to amass a huge following. His charismatic and impassioned rhetoric resonated with many Cubans who were just as frustrated with corruption and longing for change. He played a crucial role in shaping mid-20th-century Cuban politics and is often remembered for his dramatic radio broadcasts and tragic suicide, which had profound implications for the island’s future.

Early Life and Political Beginnings

Eddy Chibás was born in 1907 into the politically prominent Agramonte family, descended from Ignacio Agramonte, a key military leader in the Ten Years’ War (1868–1878). His father, a distinguished engineer educated in the United States, was politically moderate, and later became involved in politics by forming the Cuban American Friendship Council in Washington, D.C., to persuade American diplomats to withdraw support for General Gerardo Machado’s administration.

At seventeen, during a family trip to Europe, Eddy conversed with various political figures, particularly Ramón Grau San Martín, whose views aligned closely with his own. Eddy confided to his cousin Raúl Primelles that he intended to join the radical student movement at the University of Havana upon returning to Cuba. He admired its leading figure, Julio Antonio Mella.

Before attending the University of Havana, Eddy spent a year at Storm King, a boarding school in New York, as his father wanted to keep him out of trouble. Mella also inspired other students, such as Antonio Guiteras, who organized protests in Havana after government agents murdered a newspaper director.

University of Havana Political Uprising

To understand the civil unrest in Cuba that coincided with Eduardo Chibás’s early ideological development, one should look at the events at the University of Havana. The students there were inspired by uprisings at other universities, such as the revolt at Argentina’s University of Córdoba in 1918. According to the article “Old and New Politics in Cuba: Revisiting Young Eddy Chibás 1927–1940,” the gains achieved by the University of Córdoba students, including the abolition of school fees, freedom from political interference, selection of professors by competitive exams, and student involvement in national politics, became rallying cries throughout Latin America (pg. 228).

Julio Antonio Mella McPartland and other leftist students occupied the campus, demanding free tuition, independence from government control, and the dismissal of corrupt or incompetent professors. In 1924, the University of Havana began inviting various speakers to address the students, such as the Peruvian politician Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, who envisioned a democratic Latin America free from U.S. domination and communism. A year later, the Mexican political philosopher José Vasconcelos urged University of Havana students to resist both foreign and domestic tyrants (pg. 228). Mella was then expelled from the university for allegedly planting a bomb in Havana’s Payret Cinema. He denounced President Gerardo Machado, calling him a “tropical Mussolini,” which led to his imprisonment.

Political Career and Ideology

Eduardo Chibás began his political career during the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado, infamously nicknamed “The Butcher” and “The King of Latin American Assassins.” Machado’s regime favored businesses and economic interests tied to the United States. Like many who opposed the government, Chibás spent time in exile in the United States, where he came to appreciate the power of radio in shaping public discourse. He was particularly disturbed by the popular commentator Edwin C. Hill, who promoted pro-Machado rhetoric while disparaging the opposition as communists and opportunists.

Chibás’s father had formed an organization in Washington, D.C., to persuade U.S. diplomats to disassociate from Machado, but these efforts were unsuccessful. As a last resort, Eddy sent fiery letters to Ambassador Harry Guggenheim, accusing him of being complicit in the reign of terror orchestrated by Machado. Distraught over the deaths of two close friends, Chibás accused Guggenheim of being “one of those most responsible for the reign of terror.” In February 1933, Chibás shocked U.S. embassy officials in Havana by accusing Ambassador Guggenheim of condoning the torture and murder of revolutionary students. This was followed by an open letter to Secretary of State Henry Stimson, published in the Washington Herald, which repeated the charges to a wider audience and roiled State Department authorities (pg. 229).

The decline of Machado’s power was further exacerbated by the murder of Julio Antonio Mella in 1927, an act many students believed was committed by a Machado henchman. The students at the University of Havana, who formed the Directorio Estudiantil Universitario (DEU), joined forces with military men led by Fulgencio Batista to overthrow the dictatorship. This event, known as the 1933 revolution or the “Sergeants’ Revolt,” marked a significant turning point in Cuban history.

The French—Cuban Links

The social-political tension that arose in Cuba can be likened to that of the beginning of the French Revolution. The French Revolution saw radical influential political groups like The Jacobins that plotted the downfall of the king and the rise of the French Republic. They are often associated with a period of violence during the French Revolution called “the Terror” or the Reign of Terror. Secret societies were created in France such as the Occult of Reason which were against the church. These groups sprung up similarly in Cuba with radical students who organized, and there were secret groups like the ABC, who were a group of intellectuals in Cuba that plotted terrorist attacks against Machado. Cuba’s dictatorship and the monarchies of France caused grievances, and people joined together to start a coup d’état. The French Revolution led to Napoleon Bonaparte taking power like Batista did in Cuba, both of whom had the military pedigree and army on their side.

Eddy Chibás was a central figure in Cuban politics, a world-class muckraker who navigated through the regimes of three Cuban dictators. Likewise in France, Jean-François Varlet similarly engaged in political discourse, publishing articles that defended radical views and incited violence. Unlike Varlet, Chibás had technological innovation on his side with the powerful medium of radio to broadcast his messages. Although less radical and more pessimistic, Chibás sought social order and a corruption-free democracy while supporting progressive, left-leaning laws like those implemented by Grau. Much like Jean-François Varlet, whose death elevated him as a martyr, Chibás was also considered a martyr after his death, bolstered by various political groups and figures, including Fidel Castro, to gain support.

Founding the Ortodoxos

Disillusioned by the pervasive corruption within the Auténtico leadership, Chibás left the party in 1947. He then founded the Partido del Pueblo Cubano (Ortodoxo), or the Cuban People’s Party (Orthodox). The Ortodoxos advocated for social reform, anti-corruption measures, and economic nationalism. Chibás’s motto, “Shame against money” (“Vergüenza contra dinero”), encapsulated his campaign against political corruption and moral decay in Cuban society.

Radio Broadcasting and Influence

Chibás’s radio program became a cornerstone of his political strategy. He utilized the medium to reach a broad audience, denouncing corruption and calling for social justice. His broadcasts were fiery and passionate, earning him a devoted following among Cubans who were frustrated with the status quo.

Presidential Ambitions

Chibás ran for president in the 1948 election but was defeated by Carlos Prío Socarrás. Despite the loss, his influence continued to grow, and he remained a prominent political figure. Chibás’s relentless pursuit of exposing government corruption made him both a revered and controversial figure.

Mental State was a byproduct of the State

Chibás’s suicide was caused by a combination of factors. According to the article *The Political Afterlife of Eduardo Chibás: Evolution of a Symbol 1951–1991*, “The attacks against Education Minister Aureliano Sánchez Arango, which culminated in Chibás’s death, were just as ferocious as those leveled against the Supreme Court justices. In June 1951, Chibás charged that Sánchez Arango was stealing money appropriated for school breakfasts to construct a private housing development in Guatemala. The accusations led to a media war between Chibás and the education minister, with each publishing competing newspaper ads and attacking each other on separate radio programs. In newspaper ad after newspaper ad, Sánchez Arango repeatedly challenged Chibás to present the proofs (pruebas) to the public. In his defense, the education minister published a letter from the government of Guatemala, which stated that no education funds were used by Sánchez Arango to build a development there, as well as a second letter from the Compañía Nacional de Alimentos, stating that the company had never bribed anyone to receive payment for their food products” (p. 80).

However, instead of presenting any evidence of wrongdoing, Chibás, in his final radio address, likened himself to Galileo, who asserted that the earth revolved around the sun despite lacking physical proof. In a fervent plea, Chibás urged the people of Cuba to “sweep away the thieves” and continued, “Citizens of Cuba, stand up and go forward. Citizens of Cuba, wake up. This is my final plea.” The actual recordings of Chibás’s last radio broadcast reveal his passionate tone. He spoke with such vigor and conviction, refusing to mince words. He referenced Galileo’s trial for heresy to illustrate his own predicament of accusing government officials of corruption without having concrete proof.

Chibás’s inability to provide evidence led to public ridicule. People mocked him, asking, “Dónde están las pruebas? Dónde están las pruebas?” (“Where are the proofs? Where are the proofs?”). Cartoon images of Chibás with his well-known glasses appeared, captioned, “Cuando encuentre la maleta, ya verán” (“When the suitcase is found, you will see”). It was clear that Chibás was deeply offended and embarrassed by the mockery, which he did not take well.

A reporter visited Chibás’s sister-in-law in Caracas, who recounted that on the day he decided to commit suicide, he went for a walk and was mocked by people saying, “Eddy, ¿dónde dejaste la maleta?” (“Eddy, where is the suitcase?”). That day, he visited his father’s grave at the cemetery, a place he often frequented, and it was likely there that he decided to take his own life. A colleague present during the radio broadcast where Chibás committed suicide reported that the gun was hidden under his chair, and he shot himself. Writer Carlos Alberto Montaner doubts that Chibás intended to die, believing the gunshot was not meant to be fatal. However, the wound was severe, and Chibás died eleven days later.

It is believed that Chibás was in a vulnerable state, especially after his father’s death. His mental instability, combined with the backlash from his accusations of corruption, likely caused him immense misery and led to his self-destructive behavior.

The Final Broadcast and Suicide

On August 5, 1951, during one of his radio broadcasts, Chibás dramatically declared he would reveal evidence of corruption involving a high-ranking government official. However, he failed to produce the promised evidence. Feeling that his credibility and cause were severely damaged, Chibás shot himself in the abdomen at the end of his broadcast. He died eleven days later, on August 16, 1951.

Legacy and Impact

Chibás’s suicide had a profound impact on Cuban politics. It galvanized his supporters and intensified the public’s discontent with the government. His martyrdom elevated him to a legendary status among many Cubans, and his ideas continued to influence Cuban politics long after his death.

One of Chibás’s most notable political disciples was Fidel Castro, who was inspired by Chibás’s dedication to nationalism and social justice. Castro initially joined the Ortodoxo party and later led the Cuban Revolution, which ultimately overthrew the Batista regime in 1959.

Conclusion

Eduardo Chibás remains a pivotal figure in Cuban history. His fervent anti-corruption stance, passionate nationalism, and dramatic end contributed to the political turbulence that eventually led to the Cuban Revolution. Chibás’s life and legacy continue to be studied and remembered as a symbol of integrity and a relentless fight against political corruption in Cuba.

Citation:

Ehrlich, I. (2009). Eduardo Chibás: The Incorrigible Man of Cuban Politics. CUNY Academic Works, City University of New York, Graduate Center.

Smith, P. H. (2011). Old and new politics in Cuba: Revisiting young Eddy Chibás, 1927–1940. Journal of Latin American Studies, 43(2), 225–250.

Whitney, R. (2012). The Political Afterlife of Eduardo Chibás: Evolution of a Symbol 1951–1991. Journal of Latin American Studies, 44(1), 79–101.